But the excitement, especially among the country’s small Catholic population, is tempered by trepidation.

Myanmar stands accused of perpetrating ethnic cleansing against Rohingya Muslims in Rakhine state – allegations its rulers vehemently deny – and members of the Christian minority fear a strong statement from the Pope could trigger further unrest.

“Like other people, I’m afraid of what he will say about Rakhine state,” said a nervous priest named Father Paul as he swept the aisles in St Mary’s Cathedral, where the Pope is scheduled to give a mass next week. “I don’t think he will say anything,” he said.

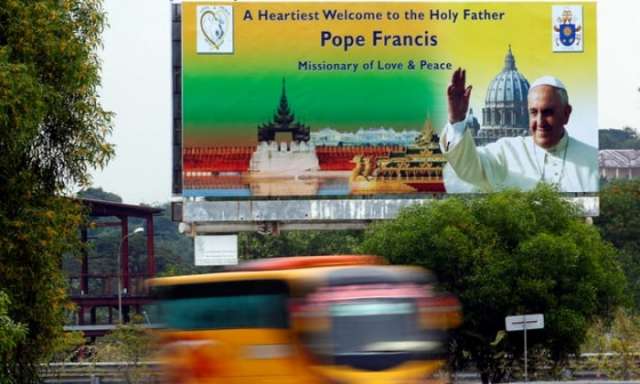

Francis will fly into Yangon on Monday and meet Aung San Suu Kyi and commander-in-chief Min Aung Hlaing in the capital, Naypyitaw, the following day. He will deliver two masses in Yangon on Wednesday and Thursday, before travelling to Bangladesh to meet Rohingya refugees.

More than 620,000 Rohingya have fled their homes in Myanmar’s northern Rakhine state since August, arriving in neighbouring Bangladesh with stories of massacres, gang rape and arson by soldiers and local Buddhists. The US, the United Nations and human rights groups have said the violence against the persecuted minority amounts to ethnic cleansing.

Francis, the first Jesuit Pope and a divisive figure whose liberal views have been met with criticism and even accusations of heresy within the church, has been a vocal advocate for the Muslim minority, calling them “our Rohingya brothers and sisters” earlier this year.

According to a source familiar with discussions, local Catholics are divided over the issue, with many sympathetic to the Rohingya but frightened that they could be the target of a nationalist backlash.

Cardinal Charles Maung Bo, the most prominent Catholic in the country, has advised the Pope not to use the word “Rohingya”, which most people in Myanmar reject in favour of “Bengali”, implying they are illegal immigrants from Bangladesh.

According to the source, one proposed solution is that Francis refers to “our brothers and sisters known as Rohingyas” or “the people who identify themselves as Rohingyas”.

“The desire of the majority, maybe not only the Catholics but also all the citizens of Myanmar, is for him not to say this thing because we know the complexity of this issue,” said Father Mariano Soe Naing, spokesman for the Bishops’ Conference of Myanmar.

He said he was relieved by a video message for Myanmar released by the Pope this week in which he said the intention of the trip was to “confirm the Catholic community of Myanmar”.

Francis also recently met Kofi Annan, the former UN secretary general who headed an advisory commission that issued recommendations for Rakhine state that have been largely accepted by authorities, he said.

“We are sure that Kofi Annan must have explained in depth the crisis and he must have understood by now if he must say something or not,” said Soe Naing.

However, the Pope is famously independent and prone to unscripted moves. On a visit to Bethlehem in 2014, he stopped his white Popemobile at the barrier between Palestine and Israel and kissed the separating wall, a gesture that angered Israelis.

“Pope Francis has made it a particular focus of his papacy to champion peace and reconciliation and to speak up for the persecuted, the poor, those on the margins, and so given the continuing very serious religious and ethnic conflicts and tensions in Myanmar, the Pope will bring a message of peace, reconciliation, justice and human dignity and I hope that message will be heard by the country as a whole,” said Benedict Rogers, East Asia team leader at Christian Solidarity Worldwide and the author of several books on Myanmar.

Nationalist leaders in Myanmar will be watching the visit closely, amid growing anger over the perception that the international community is meddling in Myanmar’s internal affairs.

Rakhine nationalist leader Dr Aye Maung, the chairman of the Arakan National party, said the timing of the visit was strange. “Why does he choose this time and situation? One has to think: is there any tension between Christians and Muslims? Or is this is the request of the Catholic people here? Or are there any problems between Buddhists and Christians? Or is his intention mainly for the Bengali and Rakhine people?” he said.

“He should avoid anything that will ignite feelings of hatred,” he said, resorting to metaphor: “Before the bird sits on the tree branch, the branch doesn’t have any vibrations, but when the bird flies out the branch is left swaying.”

Myanmar is home to about 650,000 Catholics, of whom about 150,000 are expected to travel to Yangon for a chance to see the Pope. Trains have been hired to take those living in Kachin state, in the far north, on the two-day journey to the commercial capital.

Among those who have already arrived, hopes are high. In the garden of St Mary’s, 68-year-old Lucy Lum Nyoi, from the mining town of Hpakant in Kachin state, said a glimpse of “Papa” would be like seeing Jesus.

In Kachin, government troops have been waging a long-running battle against ethnic armed groups. “We hope that he will talk about peace because we are from a place where fighting is taking place,” she said.

Her elderly brother, Isaac Lum Nyoi, beamed as he said, “I think peace will come with this visit.”

More about: