Colour is the soul of art. It’s what pulls us into the over-ripening gold of Vincent van Gogh’s Sunflowers and what whorls our spirit perilously into the existential blue of his Starry Night. Yet how many of us have given a second thought to the cultural origins of the pigments that manipulate our gaze? What would it mean to our affection for JMW Turner’s sprawling and luminous sunrises if we knew the backstory of the lilting lemon he used to conjure them? Would it change the power or poetry of Rain, Steam and Speed: The Great Western Railway if we learned that the evaporative yellows that infuse the atmosphere with mystical light were wrought from the distilled urine of cows cruelly raised on a diet consisting exclusively of mango leaves?

Joseph Mallord William Turner used Indian Yellow in his 1844 painting Rain, Steam, and Speed: The Great Western Railway (Credit: Alamy)

Thirty years ago, America found itself in the throes of a heated public debate about the merit of a provocative photograph by a taxpayer-funded artist, Andres Serrano, who had plunged a crucifix into a beaker of urine to capture the eerie atmospherics of refracting light on the sacred object. But Turner’s mistscapes are arguably more sensational even than Serrano’s Piss Christ. The diaphanous figures dancing in shimmering splendour to the left of the railway tracks in Turner’s work are sculpted from the forced waste of abused animals – the inhumanity of their treatment is fossilised forever on the clotted surface of Turner’s mesmerising canvas.

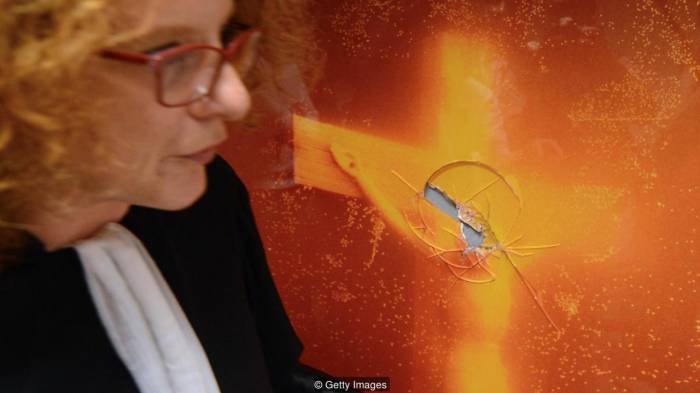

Immersion Piss Christ (1987) by US artist Andres Serrano was partially destroyed by Catholic activists in 2012 (Credit: Getty Images)

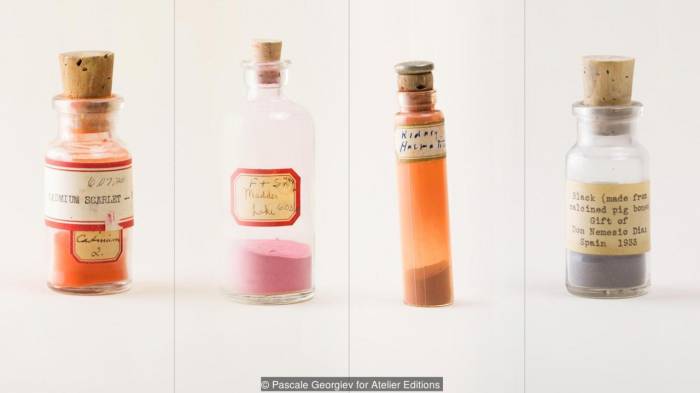

A fusty clump of so-called “Indian Yellow”, clenched roughly into a ping-pong-ball sized sphere, just the way Turner himself would have acquired the colour, is among the many hues to feature in an intriguing new book from Atelier Éditions, An Atlas of Rare & Familiar Colour, devoted to the vast cache of colours held by Harvard University in its extraordinary Forbes Pigment Collection. Harvard’s laboratory, a rich resource for scholars seeking to trace the DNA of every hue out of which the vibrancy of world culture has been constructed, houses nearly 4,000 unique specimens.

Waste of talent

The unique laboratory is the legacy of Edward Waldo Forbes (1879-1969), former director of the university’s Fogg Art Museum. A keen collector and art historian, Forbes embarked on a global search for far-flung pigments in order to better appreciate the raw materials that make up the masterpieces we see and to guard against the counterfeit allure of forgery. The cornerstone of the Forbes Pigment Collection is the countless phials filled and labelled by Forbes himself. Taken together, the assembled samples of subtle shades, which filtered their way into the studios of art history’s greatest geniuses, comprise a forensic workshop in which the mystery of the rainbow is endlessly unwoven.

Pigments from the Forbes Collection include Cadmium Scarlet, Madder Lake, Kidney Haematite and Black made from Calcined Pig Bones (Credit: Pascale Georgiev for Atelier Éditions)

If you’ve ever wondered what it is that gives everything from the white robes of Egyptian tomb painting to the pulsing purity of the lamb’s wool in Renaissance Christian icons such otherworldly immaculacy, the answer, we discover, is dung. Bovine dung, to be precise. “Created by laying lead ingots and vinegar within earthenware jars,” according to Kingston Trinder, author of the brief introductions to the book’s 10, colour-categorised chapters, “then enveloping such with layers of either tan bark or bovine excrement, the resultant lead carbonate went utilised as a white pigment”. In such light, the contemporary British artist Chris Ofili’s elephant-dung-encrusted painting, The Holy Virgin Mary (1996), which caused considerable controversy when it was exhibited in London and New York between 1997 and 1999, suddenly seems conventional in its making.

Chris Ofili’s elephant-dung-encrusted painting, The Holy Virgin Mary (1996), is not so different from a white pigment that incorporated cow dung (Credit: Alamy)

Flipping through An Atlas of Rare & Familiar Colour is to discover a rich and inspiring vocabulary of every shade into which life and art is splintered. Here, one learns to distinguish between “Cadmium Scarlet” and “Dragon’s Blood”, “Geranium Lake” and “Chinese Vermillion”, “Murez Shell” and “Alizarin Violet”. If the bovine backstory to Turner’s sunrises has put you off the magic of his skies, turn away now before I fill you in on what the topless heroine of Eugene Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People is really trudging over as she marches triumphantly forward towards freedom.

In all likelihood, the crumpled browns that describe the defeated flesh of the fallen revolutionaries whose bodies lay scattered at Liberty’s feet was, in fact, fashioned from powderised remains of long-dead and embalmed Ancient Egyptians. The pigment, known for centuries as “Mummy brown”, is the subject of a fascinating anecdote retold in the charming introduction to the volume by the art historian Victoria Finlay, author of the celebrated book, Colour: Travels Through the Paintbox, first published in 2002.

According to Finlay, the British writer Rudyard Kipling remembered his uncle, the Pre-Raphaelite painter Edward Burne-Jones, conducting a funeral procession and solemn burial for his earthen tube upon the appalling discovery that the colour had been harvested from the bodies of the dead. “Even as an old man,” Finlay writes, “Kipling wrote that he still remembered exactly where that tube of mummy brown lies.”

BBC

More about: culture