The team at the University of California, San Francisco says the technology is "exhilarating".

They add that their findings, published in the journal Nature, could help people when disease robs them of their ability to talk.

Experts said the findings were compelling and offered hope of restoring speech.

How does it work?

The mind-reading technology works in two stages.

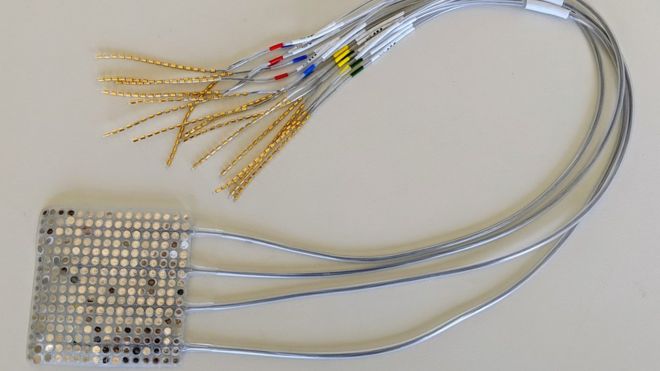

First an electrode is implanted in the brain to pick up the electrical signals that manoeuvre the lips, tongue, voice box and jaw.

Then powerful computing is used to simulate how the movements in the mouth and throat would form different sounds.

This results in synthesised speech coming out of a "virtual vocal tract".

Why do it like that?

You might think it would be easier to scour the brain for the pattern of electrical signals that code for each word.

However, attempts to do so have only had limited success.

Instead it was focusing on the shape of the mouth and the sounds it would produce that allowed the scientists to achieve a world first.

Prof Edward Chang, one of the researchers, said: "For the first time, this study demonstrates that we can generate entire spoken sentences based on an individual's brain activity.

"This is an exhilarating proof of principle that, with technology that is already within reach, we should be able to build a device that is clinically viable in patients with speech loss."

How good is it?

It is not perfect.

If you listen to this recording of synthesised speech:

You can tell it is not crystal clear (the recording says "the proof you are seeking is not available in books").

The system is better with prolonged sounds like the "sh" in ship than with abrupt sounds such as the "buh" sound in "books".

In experiments with five people, who read hundreds of sentences, listeners were able to discern what was being spoken up to 70% of the time when they were given a list of words to choose from.

Who could it help?

Many diseases can lead to the loss of speech including:

- motor neurone disease

- brain injuries

- throat cancer

- some strokes

- neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson's and multiple sclerosis

The team say it could work in some of these diseases.

However, the technology relies on the parts of the brain which control the lips, tongue, voice box and jaw working correctly. So patients with some types of stroke would not be able to benefit.

"This is not a solution for everyone who cannot communicate," says Prof Chang.

There is also the more distant prospect of helping people who have never spoken, including some children with cerebral palsy, to learn to speak with such a device, say the researchers.

What do people have to think?

The participants in the study were told not to make any specific mouth movements.

Prof Chang said: "There were just asked to do the very simple thing of reading some sentences.

"So it's a very natural act that the brain translates into movements itself."

Can unscrupulous people read my private thoughts?

At the moment it is too hard.

Prof Chang said: "We and others actually have tried to look at whether it's actually possible to decode just thoughts alone.

"And it turns out, it's a very, very difficult and challenging problem.

"That's only one reason why, of many, we really focus on what people are actually trying to say."

However, some scientists have argued there is an ethical debate to be had about brain-machine interface technologies that read the mind.

What do the experts say?

A commentary, published alongside the research, said the results were "compelling".

It added: "We can hope that individuals with speech impairments will regain the ability to freely speak their minds and reconnect with the world around them."

Prof Sophie Scott, from University College London, said: "This is very interesting work from a great lab but it must be noted that it is at very early stages and is not close to clinical applications yet."

More about: science