by Jonathan Glancey

Castello di Sammezzano, Leccio, Italy

The mesmerising ceiling, vaults and decor of the Peacock Room in this abandoned Italian palazzo near Florence speak for themselves. Peacocks, and other exotica, were the source of the inspired decoration to be found throughout the seemingly endless empty rooms of this daydream building. The Moorish-style makeover of what was a much older palace was the life work of Ferdinando Panciatichi Ximenes d’Aragona. Although the aristocratic Italian architect, engineer, botanist, philosopher and politician never visited the Levant or the Orient, he imagined a world of exquisite and highly exotic forms and colours that he brought to life in Leccio between 1843 and 1889. A hotel in the 20th Century, the palazzo and its polychromatic Peacock Room are in limbo today. (Credit: Antonio Cinotti/Flickr cc by 2.0)

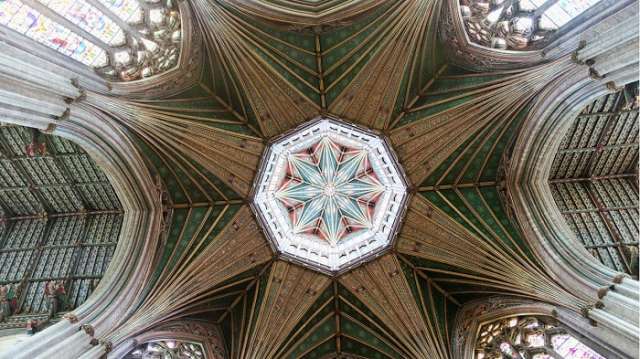

Ely Cathedral, Cambridgeshire

Completed in 1334 by the royal carpenter William Hurley, the exquisite timber lantern over the central octagonal tower of Ely Cathedral is one of the greatest feats of medieval structural engineering and design. From the cathedral floor, the lantern appears like the centre of a great, eight-pointed star, with a carving of Christ in Glory at its centre. Constructed primarily from eight English oak trees, the 30ft-high lantern is supported by highly visible timber fan vaulting and by a hidden tent-like lattice of oak beams. Wooden panels – decorated with painted angels in the 19th Century – can be opened around the lantern. Choristers, serving as a heavenly choir, sang through these from the roof of the fenland cathedral. (Credit: Steve Vidler / Alamy Stock Photo)

Solna Centrum Metro Station, Stockholm

By far the most alluring attraction of Stockholm`s Solna Centrum shopping mall is the Blue Line Metro station that has served it since 1975. Artists Anders Åberg and Karl-Olov Björk painted the exposed bedrock of the underground concourse a thrilling and beautifully lit night-time red. Riding the escalators here is like being drawn into, or escaping from, some mythical sorcerer`s cave. Since 1957 more artists than it would take to fill the carriage of a Metro train have conjured 94 of the network`s 100 stations into memorable public artworks, justifying the widely quoted description of the 70-mile Stockholm Metro as "the world`s longest art gallery". Perhaps only the Moscow Metro, mostly of an earlier era, rates alongside this remarkable achievement. (Credit: David Bertho / Alamy Stock Photo)

Grand Central Station, New York

For decades the zodiac ceiling of the imposing and much loved concourse of Grand Central was largely invisible. It was covered in thick layers of nicotine tar, the result of countless cigarettes smoked by generations of commuters making their way to the station`s 67 platforms set below the imposing Beaux-Arts style building designed by Warren and Wetmore, and Reed and Stern. Based on medieval astronomical maps, it was painted by the French artist Paul César Helleu and New York`s Charles Basing with a team of assistants. The signs of the zodiac were outlined in gold leaf on a blue-green backdrop evoking autumn and winter night skies of Greece and Southern Italy. The cleaned and restored ceiling was unveiled in 1998. (Credit: Patrick Shyu / Alamy Stock Photo)

Shah Mosque, Isfahan

In 1598, Shah Abbas moved the Persian capital to Isfahan. Here, he commissioned a remarkable sequence of ambitious and beautiful religious and civic buildings. But, because the only readily available building material in Isfahan was baked mud brick, there was a fear that, however grand, the new buildings would look rather dull. New techniques in firing coloured mosaic tiles, however, allowed the Shah`s architects to revel in wondrous displays of decoration, brought to perfection here in the Shah Mosque (1612-38). Designed by the master calligrapher and miniaturist Rezza Abbasi, the blue, yellow, turquoise, pink and green tiles catch and reflect the light of this bright and hot city, animating cool spaces under the great blue dome of Abbas`s mosque. (Credit: Hossein Lohinejadian / Alamy Stock Photo)

Haesley Nine Bridges Golf Club House, Yeoju-gun, South Korea

Designed by Shigeru Ban, the Japanese architect famous for a new generation of paper and cardboard buildings, this country club opened in 2010 features a notably elegant atrium lobby. A laminated timber grid shell supported seamlessly by lightweight, three-storey-high columns of the same material forms its ceiling and roof. Computer cut, columns and grid shell employ as little material as possible. The filigree, fireproof columns allow the free flow of air through the atrium, their design inspired by ‘bamboo wives’ [zhúfūrén], traditional lattice-framed bamboo bolsters. In hot and humid weather, these are cooler to sleep on than sheets and pillows. The lightweight form of the ceiling grid shell is reflected in a pool creating an intentionally poetic effect. (Credit: Kyeong Sik Yoon/KACI International) and Shigeru Ban/SBA Architects)

Heydar Aliyev Centre, Baku, Azerbaijan

The floor, walls and ceilings of the curvaceous auditorium of this bravura cultural centre, opened in 2012, form a seamless whole. The effect is magical and truly remarkable, as if the architect, Zaha Hadid has dissolved the normal rules of construction and reinvented their own. In fact, the geometrically complex laminated white-oak shell of the auditorium is set within a steel frame. This gives the necessary rigidity to the structure while allowing and the auditorium to feel as if it is floating in free space. Zaha Hadid had long wanted to shape such a fluid architecture. With the latest computer wizardry, she has achieved this in Baku. You will never look at a ceiling in quite the same way again. (Credit: VIEW Pictures Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo)

San Pantalon, Dorsoduro, Venice

For a few awe-inspiring moments, a 50-cent euro coin lights up the ceiling of this unfinished Baroque parish church. A dazzling late 17th Century oil painting covering 443 sq m (4768 sq ft) gives the illusion of continuing the architecture of the church up through chiaroscuro colonnades and a choir of highly animated winged angels through golden skies to the white light of heaven itself. This illusionistic painting, with its thrillingly foreshortened perspectives, is the work of Gian Antonio Fumiani (1645-1710). The influential 19th Century English critic, John Ruskin, described The Martyrdom and Apotheosis of St Pantalon as "the most curious example in Europe of the vulgar dramatic effects of painting." He was quite wrong: dig in your pocket for another 50 cents. (Credit: Sylvain Sonnet/Corbis)

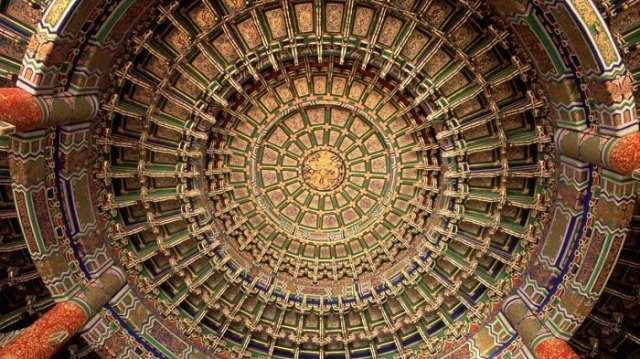

Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests, Temple of Heaven, Beijing

Temple of Heaven is a vast complex of religious buildings built during the reign of the Ming Dynasty Yongle emperor (born Zhu Di). Completed in 1420, the three-tiered Hall of Prayer evoked and represented the hours, days, months and seasons of the years in an architecture of precise geometry and gloriously colourful timber components culminating in an imperious dome. The 125ft (38m) high temple was constructed without a single nail, the timber columns and rafters slotting together like a giant building kit. The distinctive colours represent various evocations of good fortune, joy, prosperity and the glory of imperial rule. Burned down in 1889 and rebuilt, the temple interior was repainted to look brand new for the 2008 Beijing Olympics. (Credit: John Slater/CORBIS)

St Stephen Walbrook, City of London

Viewed from the confine of City lanes, St Stephen Walbrook appears to be a very modest structure. Inside, however, this church designed by Christopher Wren proves to be one of the architectural wonders of late 17th Century Europe. Carried on eight Corinthian columns and eight arches punctuated by clear windows, is a magnificent coffered dome. This is a scale-model of the dome Christopher Wren had hoped to build over his original design for St Paul`s Cathedral. The Church Commissioners turned this down, and yet we can see what Wren had intended inside this quiet church . Although capacious, the 63ft (19.3m) dome - made of timber, plaster and copper - is, unlike that of St Paul`s, light, resting gently on St Stephen`s. (Credit: Graham Prentice / Alamy Stock Photo)