Our modern civilisation may be the most advanced to ever exist on Earth, but around 100 generations ago, our ancestors had brains that were larger than our own.

Your ancestors had bigger brains than you. Several thousand years ago, humans reached a milestone in their history – the first known complex civilisations began to emerge. The people walking around and meeting in the world's earliest cities would have been familiar in many ways to modern urbanites today. But since then, human brains have actually shrunk slightly.

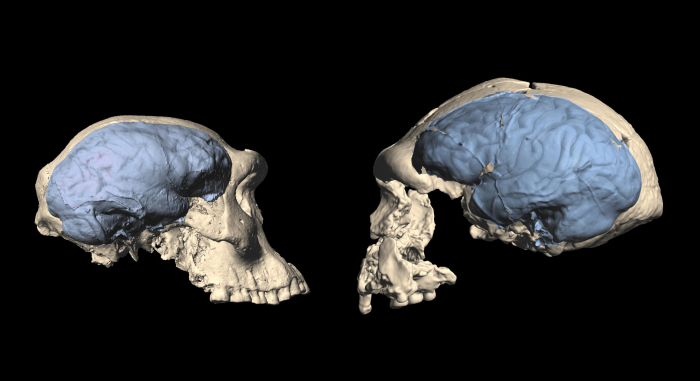

The lost volume, on average, would be roughly equivalent to that of four ping pong balls, says Jeremy DeSilva, an anthropologist at Dartmouth College in the US. And according to an analysis of cranial fossils, which he and colleagues published last year, the shrinkage started just 3,000 years ago.

"This is much more recent than we anticipated," says DeSilva. "We were expecting something closer to 30,000 years ago."

Agriculture emerged between 10,000 and 5,000 years ago, although there is some evidence that plant cultivation may have started as early as 23,000 years ago. Sprawling civilisations, full of architecture and machinery, soon followed. The first writing appeared at roughly the same time. Why, during this age of extraordinary technological development, did human brains start to dwindle in size?

It's a question that has left researchers scratching heads. And it also raises questions about what the size of a brain really reveals about an animal's intelligence, or cognitive ability, in general. Many species have brains far bigger in size than ours and yet their intelligence – as far as we understand it – is quite different. So the relationship between brain volume and how humans think can't be a straightforward one. There must be other factors, too.

What exactly prompts brains to get bigger or smaller over time in a given species also is often difficult to know. DeSilva and his colleagues note that human bodies have got smaller over time but not enough to account for our reduction in brain volume. The question as to why this change occurred still hovers. And so, in a recent paper, they sought inspiration from an unlikely source – the humble ant.

At first glance, or should I say squint, ant brains might seem hopelessly different to ours. They are roughly one tenth of a cubic millimetre in volume – or a third the size of a grain of salt – and contain just 250,000 neurons. A human brain, by comparison, has around 86 billion.

But some ant societies share striking similarities with our own. Amazingly, there even are ant species that practise a form of agriculture in which they grow huge swathes of fungus inside their nests. These ants gather leaves and other plant material to use on their farms before harvesting the fungus to eat. When DeSilva's team compared the brain sizes of various ant species, they found that sometimes those with large societies had evolved bigger brains – except when they had also evolved this penchant for fungus-farming.

It suggests that, for an ant at least, having a bigger brain is important for doing well in a large society – but that more complex social systems with greater division of labour might, in contrast, prompt their brains to shrink. That could be because cognitive capabilities get divided up and distributed among many members of the group, who have various roles to play.

In other words, intelligence goes collective.

"What if that happened in humans?" says DeSilva. "What if, in humans, we reached a threshold of population size, a threshold in which individuals were sharing information and externalising information in the brains of others?"

One other possibility is that the emergence of writing – which occurred roughly 2,000 years before the reduction in human brain size set in – also had an effect. Writing is one of relatively few things that separates us from all other species and DeSilva questions whether this could have influenced brain volume through “externalising information in writing and being able to communicate ideas by accessing information that’s outside your own brain”.

The many differences between ant and human brains mean we should be cautious about drawing parallels too hastily. That said, DeSilva argues the possibility is a useful starting point for thinking about what caused the notable, and relatively recent, reduction in human brain volume.

These ideas remain hypotheses for now. There are lots of other theories that attempt to explain human brain size reduction. However, quite a few of them become implausible if brain shrinkage really did start as recently as 3,000 years ago. A good example is domestication. Dozens of different animals that have been domesticated, including dogs, have smaller brains than their wild ancestors. But human self-domestication is estimated to have occurred tens of thousands, or even hundreds of thousands, of years ago – long before the big brain shrink.

But do smaller brains mean that, as individuals, humans became stupider?

Not really, unless you are talking about subtle differences across a large population. In 2018, a team of researchers analysed a huge volume of data from the UK Biobank, a vast biomedical database that contains, among other things, brain scans and IQ test results for thousands of people.

At 13,600 people, it had a bigger sample than all previous studies on brain size and IQ combined, says the study's co-author Philipp Koellinger, a behavioural geneticist at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, in the Netherlands.

The study found that having a bigger brain was, on average, associated with doing slightly better on IQ tests but, crucially, the relationship was non-deterministic. That means that there were some people who did very well on the tests despite having relatively small brains and vice versa.

"There is really no very strong relationship," says Koellinger. "It is just all over the place."

That's important partly because of how people have historically tried to categorise and sort individuals based on things such as the size or shape of their heads.

"There is a very ugly history in the Western world, the eugenics movement and all these sorts of things that have been based on these ideas about biodeterminism," says Koellinger. "The correlations that we report do not imply any sort of biodeterminism."

Because the brain scans also revealed certain information about the structure of people's brains, not just their size, the study was able to detect something else that might be going on. It found a relationship between the volume of grey matter – the outer layer of the brain, which has a particularly high number of neurons – and IQ test performance.

In fact, structural differences like that are probably more meaningful in terms of a person's general cognitive ability than the sheer size of the brain organ.

"It would be crazy to think that the volume can explain the entire difference," says Simon Cox, who studies brain ageing at the University of Edinburgh. It might even be one of the least important factors, he adds.

This makes sense when you think about it. Men's brains are generally about 11% larger by volume than women's brains because of their larger body size. But studies have found that, on average, women have the advantage with some cognitive abilities, men on others.

Cox points out that other research in which he has been involved that reveals how women's brains may compensate for being smaller via structural differences. For instance, women have, on average, a thicker cortex (the layer that contains grey matter).

There are many features and facets of brains that appear to affect cognitive ability. Another example is myelination. This refers to the sheath of material that surrounds axons, the long, thin "cables" that allow neurons to connect to other cells and form a neural network.

When people age, their myelin breaks down, reducing the efficiency of the brain. It's possible to detect this change by studying how easily water diffuses across brain tissue. With reduced myelin, the water flows more easily. This is indicative of cognitive decline.

The brain remains "phenomenally complex", says Cox, and it is difficult to know exactly what difference the structural make-up of a particular brain will have on a person's intelligence. It's also worth noting that some people have partial brains, due to injury or quirks of development, and yet seem surprisingly unaffected. One man in France who was a successful career as a civil servant was found to be missing 90% of his brain and yet had an IQ score of 75 and a verbal IQ of 84 – only slightly below the French average of 97.

Exceptions can never be interpreted as the rule, though. Ultimately, multiple studies do suggest statistically significant, albeit subtle, links between brain volume, structure and intelligence.

All of this gets even more interesting when you consider the different brains of the animal kingdom. We've already explored one comparison, between human and ant brains, but what about other species? What prompts big – or small – brains to evolve?

Amy Balanoff, who studies brain evolution at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, says that brain tissue requires a lot of energy to grow and maintain, so a species is not likely to evolve a large brain unless it needs it. Think of parasitic creatures that rely on relatively stable environments and resources, she suggests. Lampreys have notoriously small brains of just a few millimetres long, for example.

"They don't really need to spend that extra energy on neural tissue which is really metabolically expensive," says Balanoff.

Also, some animals appear to have developed larger brains, relative to their body size, over time – but their brains haven’t actually changed, their bodies have just got smaller. This applies to bird species, Balanoff explains.

Then there are animals that appear to have evolved specialised brain regions, which pump up the overall size of their brains compared to similar species. Take mormyrid fish, which have pretty big brains relative to their body size – similar in proportion to humans, in fact. These fish use electrical charges to communicate with one another and detect prey and in 2018 researchers found that a particular part of their brain, the cerebellum, is unusually hefty. No one is quite sure why this is but the authors of that study speculated that it could help the fish process electro-sensory information.

In humans, one area of the brain that marks us out is the neocortex, which is involved in higher cognitive function – conscious thought, language processing and so on. We undoubtedly rely heavily on these things and so it makes sense that our brains would be tailored to our needs.

Given that lots of energy is required to keep the cogs turning, it's interesting to note that animals with large brains have evolved to acquire lots of energy early in life, says Anjali Goswami, a palaeobiologist at the Natural History Museum in London.

Think of the nutritional boost that birds get even while in the egg, or which mammals receive through the placenta or from breast milk. Human babies are actually born with an excess of neurons, 100 billion, and this number declines as they develop. This is because brains fine-tune themselves depending on development and an individual's environment. Only the really necessary parts of the neural network are retained as we age but having a brain well-stocked with neurons to begin with makes that possible.

Mammals evolved in the shadow of dinosaurs, says Goswami. They needed extremely good sensory capabilities to survive, which is probably why they developed nocturnal habits and night vision. That almost certainly had an impact on neural development. As did the requirement for primates, including our ancestors, to develop the specialised motor skills required for swinging through trees.

The environment, then, put pressure on mammal brains to evolve capabilities that helped us get out of sticky situations. Lots of animals have likely benefitted from having to step up their cognitive prowess in a world full of challenges.

One study found that birds that colonised oceanic islands, and therefore had to adapt to unpredictable new territory, possessed larger brains than their mainland counterparts.

By now it should be clear, though, that you can't just measure the size of an animal's brain, compare that to the size of its body, and come to hard conclusions about how intelligent that animal is. Size is just one piece of the puzzle.

What's cleverer, anyway, to think – or to survive? Humans love to cogitate but, as Goswami says, our ability to plan looks very poor indeed when you consider our current struggles to deal with long-term, existential problems such as the climate crisis.

Cox makes another point: "There are many more things to life than having a higher general score of cognitive ability, or a high IQ."

It almost makes you wish our brains were smaller still.

BBC

More about: