Study co-author Piotr Winkielman, from the Warwick School of Business at the University of Coventry in England and the University of California at San Diego, said the findings appear to undercut the notion that female attraction is primarily dependent upon "hormonal influences" that are believed by some researchers to be the primary subconscious driver of a woman`s mate selection.

Another strong influence on our personal preference, he said, is "our lazy brains."

"If you look at a face without asking any questions, you`ll say, `That looks like a pretty face,`" Winkielman said in an interview. "But if you`re told to figure out the person`s gender, that requires more mental effort and our lazy brains don`t like mental effort and that`s obviously going to be more difficult."

"We`ve known for a while that making things effortful on the mind leads to people disliking things," he added.

The findings are published in the international journal PLOS ONE.

Winkielman said the study sheds light on how cultural forces influence perception, especially when it comes to how we form split-second first impressions at a job interview or in a bar.

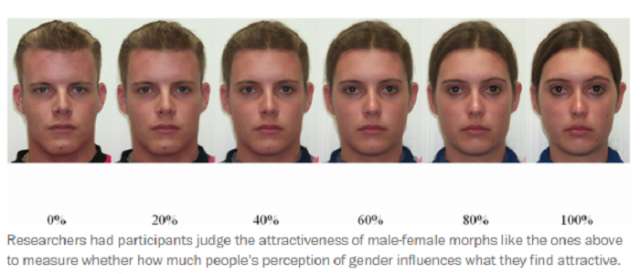

To reach their findings, Winkielman and his co-author — professor Jamin Halberstadt of the Department of Psychology at New Zealand`s University of Otago – had participants look at photos of gender-blended face morphs and rate their attractiveness during two separate experiments.

During the first experiment, participants were told to judge the faces after a gender had been assigned to them.

"The idea we tested is that the mental effort of having to assign a gender to an ambiguous face has a flow-on effect of negatively influencing how we feel about that face," Halberstadt said in a news release.

The mental effort is known as "processing fluency," which is a way of measuring the effort required for the brain to perceive, process and categorize something.

Winkielman noted that participants tended to take longer when making their assessment, which he attributed to them expending more time and energy categorizing a face to make a judgment about its beauty.

"The brain is trying to economize and do things efficiently," he told The Post. "If you can get the same product for a lesser price, then you`ll like the one that takes less effort to get. The brain adds the cost of effort to the value of the product."

In the second experiment, participants were asked to rate the attractiveness of the the gender-ambiguous faces after they`d been assigned an ethnicity. During that experiment, researchers said, the subjects did not find the gender blends less appealing.

Participants more often preferred the more feminine faces, Winkielman said. But that changed when the context of the experiment changed and the viewer was asked to consider faces within "rigid gender boxes, which can negatively color the impression of the face."

"These rigid gender categories create difficulties for people who fall somewhere in-between genders and maybe create an unnecessary reduction in their likability," he said.

Winkielman cautioned against jumping to the conclusion that categorization is a categorically negative way of understanding the social world.

It`s useful to a point, he said, like when we`re classifying someone as a "doctor" or "lawyer" or "east or west coaster." But at some point, he said, our penchant for categorizing the world around us leads to diminished returns that provide us with less information, not more.

Instead of fitting people into strictly defined boxes, which may appear to make things easier on the brain, Winkielman said the findings hint at an alternative.

"The same way we give people the option of being mixed race, lets open up the space and approach a person as a human being," he said. "Instead of asking whether we find someone a beautiful man or woman, we should ask, `is a beautiful human being?`"