The researchers found teenagers were better at a picture-based learning game than adults when positive reinforcement was involved, and they argue this sensitivity to reward could be part of an evolutionary adaptation to learn from their environment.

Teens` brains are wired differently from adults, the study found, explaining both their wild behaviour and their ability to memorise.

`The adolescent brain is adapted, not broken,` said Dr Juliet Davidow, co-author and psychology researcher at Harvard University.

`The imbalances in the maturing teenage brain that make it more sensitive to reward have a purpose - they enable adolescents to be better at learning from their experiences.`

Dr Davidow and her colleagues, including Professor Daphna Shohamy from Columbia University`s Zuckerman Institute, and Adriana Galván from the University of California, set out to test whether teens` sensitivity to reward could also make them better at learning from good or bad outcomes.

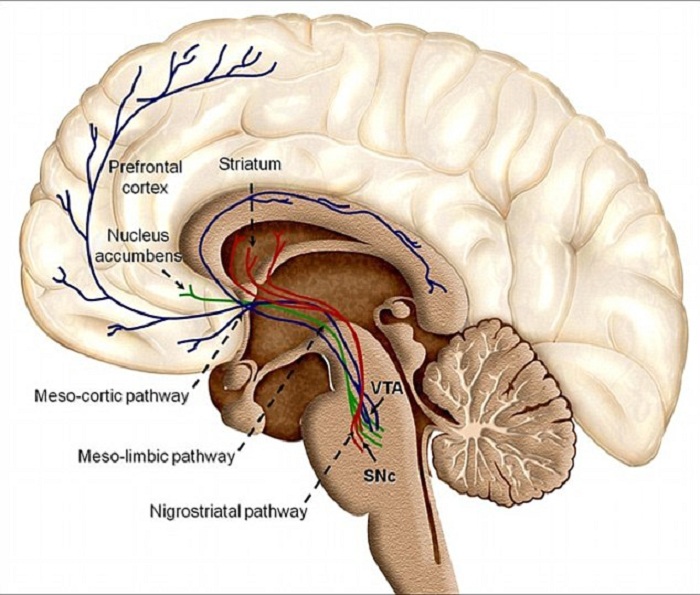

It all comes down to the coordinated activity of two distinct regions called the striatum and hippocampus - a phenomenon that is unique to youngsters.

The striatum is the area of the brain involved in releasing dopamine.

Professor Daphna Shohamy, of Columbia University in New York, lead author of the study said: `Studies of the adolescent brain often focus on the negative effects of teens` reward-seeking behaviour.

`However we hypothesised this tendency may be tied to better learning.

`Using a combination of learning tasks and brain imaging in teens and adults we identified patterns of brain activity in adolescents that support learning - serving to guide them successfully into adulthood.`

The study of 41 teens and 31 adults first focused on the striatum which controls planning, decision-making and something called reinforcement learning.

The subjects were presented with a picture of a butterfly and then a pair of flower pictures, and asked to guess which flower the butterfly would land on.

They could work out which flowers the butterfly would land on using trial and error.

Dr Davidow said: `In simplest terms reinforcement learning is making a guess - being told whether you`re right or wrong and using that information to make a better guess next time.

`Essentially it`s a reward signal that helps the brain learn how to repeat the successful choice again.`

If participants selected the right flower, the word `correct` would flash on their screen, and if they guessed wrong, it would say `incorrect` instead.

With every answer, an unrelated image - for example, a watermelon or a pencil - would also be displayed when the `correct` or `incorrect` label appeared.

These images were later used in a memory test to examine how well the subjects remembered their environment during the learning process.

The study, published in the journal Neuron, found adolescents performed better than adults in this game.

Brain scans of each participant while they were performing learning tasks were expected to show the teens` superior abilities were due to a hyperactive striatum.

Dr Davidow said: `But surprisingly, when we compared the brains of teens to those of adults, we found no difference in reward-related striatal activity between the two groups.

`We discovered the difference between adults and teens lay not in the striatum but in a nearby region - the hippocampus.`

This is the brain`s memory HQ and further analysis revealed more activity here for teens - but not adults - during reinforcement learning.

Moreover, that activity seemed to be tightly coordinated with activity in the striatum.

To investigate this connection, the researchers slipped in random and irrelevant pictures of objects into the learning tasks, such as a globe or a pencil.

The images - which had no bearing on whether the participants guessed right or wrong - served as a kind of background noise during the tasks.

When asked later on, both adults and teens remembered seeing some of the objects, but not others.

However, only in the teens was the memory of the objects associated with reinforcement learning, an observation that was related to connectivity between the hippocampus and striatum in the teen brain.

`What we can take from these results isn`t that teens necessarily have better memory, in general, but rather the way in which they remember is different,` said Dr Shohamy.

`By connecting two things that aren`t intrinsically connected, the adolescent brain may be trying to build a richer understanding of its surroundings during an important stage in life.`

Previous studies have shown adolescence is a time when powerful memories are formed, which the authors argue could be due to this enhanced connectivity between the hippocampus and striatum.

`Broadly speaking, adolescence is a time when teens begin to develop their independence,` said Dr Shohamy.

`What more could a brain need to do during this period than jump into learning overdrive?

`It may be the uniqueness of the teen brain may drive not only how they learn, but how they use information to prime themselves for adulthood.`

More about: