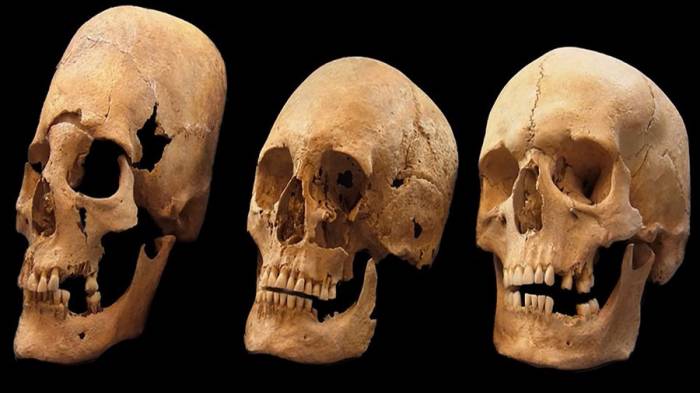

The technique used to form the women's spiked scalps, scientifically known as artificial cranial deformation (ACD), could have only been applied during childhood when the bones were still forming and the skull was still soft and malleable. Egg-shaped skulls, as with most body modifications in ancient times, were seen as a sign of beauty, status or nobility, the researchers reported. The findings were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on Monday.

To unlock the mystery of the egg-shaped skulls, researchers looked at the DNA of 36 adults, 14 of whom had altered skulls, from six different Bavarian cemeteries. They also took DNA samples from a Roman soldier and from two women from Crimea and Serbia.

The DNA test showed that the cone-headed women had vastly different genetics than their Baiuvarii counterparts. All the people with deformed skulls analyzed in the research were found to originate from southern and southeastern Europe, with DNA coding for brown eyes and blond or brown hair, as opposed to their blonde-haired, blue-eyed Baiuvarii counterparts.

The archaeologists could not locate any children with cone-shaped skulls in the graveyard, dispelling the theory that the Baiuvarii practised skull-lengthening. In addition, the women were buried with local artifacts, indicating they had adapted to local culture. The new study shows they were long-headed, immigrant brides who traveled to Bavaria from an area within modern-day Romania, Bulgaria or Serbia during the sixth century A.D.

The cone-headed concubines had likely embarked upon the journey in order to cement strategic alliances during a time when the collapse of the Roman Empire had created somewhat of a power vacuum across Europe. Germanic peoples such as the Goths, Alemanni, Gepids and Longobards swept in to fill the gap and seize territory and power for themselves. The mysterious brides were discovered in a cemetery belonging to the Baiuvarii.

RT