Dreams have fascinated philosophers and artists for centuries. They have been seen as divine messages, a way of unleashing creativity and, since the advent of psychoanalysis in the 19th Century, the key to understanding our unconscious. As so many of us have been experiencing unusually vivid dreams in recent weeks, it seems an opportune moment to explore the way in which they have been understood and depicted throughout the centuries. In doing so we may even find some intriguing parallels with our own experiences.

But why are we dreaming so vividly now? “We’re in a new situation so there’s new emotions to process,” says psychotherapist Philippa Perry, who was inundated with replies when she recently asked her followers to send her their dreams on Twitter. We make up narratives to make sense of those feelings that in dream manifest themselves “not straightforwardly but in metaphors”, she explains.

Dream Vision (1525) by Albrecht Dürer is the first known depiction of an artist’s personal dream in Western art (Credit: Getty Images)

Albrecht Dürer’s Dream Vision (1525) is the first known depiction in Western art of an artist’s personal dream. The watercolour, seemingly hastily produced on waking, shows a deluge of water descending from the sky to engulf him. “I awoke trembling in every limb and it took a long time for me to recover,” he noted.

Perry says that although her training taught her there was no such thing as a dream dictionary, decades of practice have shown her that “certain objects usually stand for a certain thing”, and “if somebody dreams about water that is usually about feelings”. To her, it sounds as if Dürer was “drowning in feelings”, and although of course she cannot be sure what those feelings were, “most of us, whether we admit it or not, or are ignorant of it when awake, fear annihilation and oblivion”, she says.

Perhaps it is unsurprising that many of the dreams Perry was sent on Twitter also involved people being engulfed with water, although the woman who dreamt she was surfing on a tsunami was clearly dealing with her emotions better than Dürer.

Renaissance artists favoured biblical stories such as Jacob’s Dream, painted for a ceiling in the Vatican’s Palazzo Apostolico by Raphael in 1518 (Credit: Getty Images)

Dürer’s personal portrayal was, however, very much the exception. Although the Renaissance had stimulated interest in ancient philosophy’s study of dreams, this had to be reconciled with prevailing Christian ideology, which frowned upon pagan interpretations. Most paintings of dreams were biblical in nature.

The dreams of Jacob – as well as those Joseph interpreted for the Pharaoh – were favourite subjects: Raphael painted them on to a ceiling in the Vatican’s Palazzo Apostolico in 1518. The vivid metaphors of the dreams are shown in spheres floating in the sky as if to emphasise that their comprehension was beyond mortal man.

Mythological themes, such as Lorenzo Lotto’s Sleeping Apollo and the Muses with Fame (1549), could, however, give artists licence to suggest the relationship between dream and inspiration. Apollo’s slumber appears to have given the muses free rein to throw off their clothes and frolic naked in the neighbouring meadow, suggesting the uninhibited creativity that sleep can unleash.

The nightmarish contents of paintings by Hieronymus Bosch resonated with a far greater number of people. Their imagery was almost certainly understood not simply as the artist’s representations of paradise and hellfire, but as representations of admonitory nightmares that might be visited on sinners to warn them of what awaited them should they not repent. This is made explicit in The Vision of Tundale (c 1520-30) by a follower of Bosch, in which the sinful knight is seen hovering above his own nightmare vision of hell.

Grotesque depictions of heaven and hell were painted by Bosch and his followers – one of whom created The Vision of Tundale (c 1520-30) (Credit: Alamy)

Dreams as artistic subject matter largely fell out of favour in the rational era of the Enlightenment but the late 18th Century saw the creation of one of the most famous depictions – The Nightmare (1781) by Henry Fuseli. Without literary, biblical or art-historical precedent, it has continued to defy interpretation, although some see it as prefiguring Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytical theories.

Perry doesn’t view the painting as a straightforward portrayal of nocturnal horrors. Instead, she sees in the defenceless pose of the woman, the horse’s unhealthy interest in her crotch, and the pose of the gremlin – which might suggest he is about to defecate on her – a “degradation of woman wet dream that many a man might have”. Or, she adds, “a woman… our dreams and our sex fantasies are rarely politically correct, whatever gender we are.”

‘Draw your dreams’

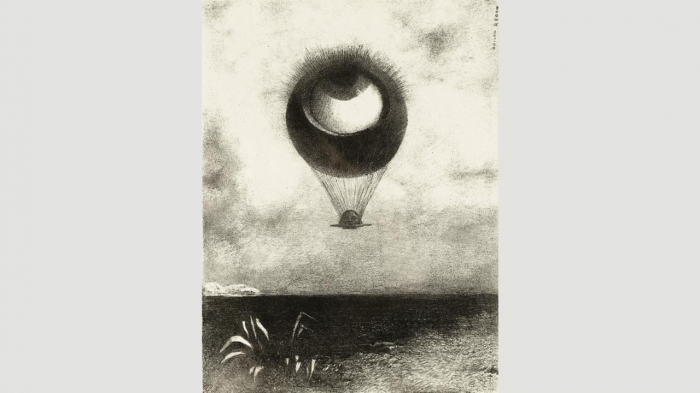

It was the Symbolists who returned dreams to the forefront of artistic expression. For artists such as Gustave Moreau and Odilon Redon, dreams were a method of deciphering reality and the mysteries of existence. Redon’s The Eye Like a Strange Balloon Mounts Towards Infinity (1882), in which a hot air balloon in the form of an eye appears to be lifting a man’s head into the clouds, suggests the often incongruous imagery of dreams. It comes as no surprise that the movement had an impact on the Surrealists.

Surrealism’s primary inspiration came from Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams. According to Freud, dreams are an expression of wish fulfilment distorted by self-censorship into imagery that makes no sense to the dreamer upon waking. By unlocking their hidden meaning, he believed that psychoanalysis could cure patients of whatever was afflicting them.

The Nightmare (1781) by Henry Fuseli is one of the most famous depictions of a dream – it continues to defy interpretation (Credit: Getty Images)

However, where Freud saw dreams as something to be deciphered in order to cure, the Surrealists saw them as a means of unleashing uninhibited creative expression; a reaction against the bourgeois culture of Europe they had come to loathe in the aftermath of World War One.

In Surrealist art, the dreamer is not usually depicted. Instead, the viewer is directly confronted with the inner workings of the dream. In Giorgio de Chirico’s anxiety-laden dreamscapes or Max Ernst’s curious paintings, collages and multimedia work dreams take the form of puzzles that challenge the viewer’s perceptions of reality.

The Eye, like a Strange Balloon, Mounts toward Infinity (1882) by Redon made an impact on the Surrealists (Credit: Getty Images)

Freud, it has to be said, was bewildered by their ideas, although he did slightly change his tune when he met Salvador Dalí in 1938. Dalí had brought with him his painting Metamorphosis of Narcissus (1937), in which the form of Narcissus gazing into a pool is duplicated by a finger and thumb clutching a cracked egg from which a Narcissus flower appears. Previously Freud had seen the Surrealists as “absolute (let us say 95%, like alcohol), cranks” – but Dalí, with his “undeniable technical mastery”, made him reconsider his opinion.

Perry herself explored the Surrealist approach to dreams when she made the BBC Four documentary How to be a Surrealist with Philippa Perry in 2017. Like them, she set up a Bureau of Surrealist Research and asked the public to tell her their dreams before asking them to draw them. “What is so moving is what they got from it when they relived their dreams,” she says.

Surrealist dream paintings, such as Metamorphosis of Narcissus (1937) by Salvador Dalí, depict the inner workings of a dream (Credit: Alamy)

With patients, Perry generally uses Gestalt therapy, pioneered by the German psychiatrist Fritz Perls, which involves retelling your dreams to yourself from the point of view of all the objects in the dream. The idea is that everything in your dream is a part of you, so you’ll know what they’re going to say and will thus gain a better understanding of yourself.

In our current situation, Perry thinks multiple approaches will have benefit. “Draw your dreams; write the dreams down. All these things help you process the emotion and the feeling in the dream. You take ownership and therefore you take control,” she says.

And, who knows, in the process, we might unleash our own, hitherto unknown, creativity.

BBC

More about: dreams