By Vasif Huseynov

Interstate armed conflicts often cause extensive destruction and degradation of the natural environment in addition to their immediate catastrophic implications for the lives of people in the conflict zones. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) reports that such conflicts have been the single most important predictor of the decline of certain wildlife populations between 1946 and 20102. The environment, often, as the ICRC aptly puts it, a neglected victim of such conflicts, is damaged not only in the course of the war, but also in its aftermath, owing to the collapse of the institutions tasked with the protection of nature.

The environmental cost of a conflict soars dramatically when the region is covered with dense forests rich with endemic flora and fauna. The nature of Azerbaijan’s Nagorno- Karabakh and surrounding regions is such that they can be included in this category. In the wake of the fully-fledged war that Armenia waged against Azerbaijan in 1988–1994, Baku lost control over this region, which constitutes about 20 per cent of Azerbaijan’s internationally recognized territories. The four UN Security Council resolutions of 1993 that demanded the immediate withdrawal of Armenian troops from the occupied Azerbaijani territories have yet to be implemented.

According to the surveys that Azerbaijan made prior to the occupation, there were more than 460 native tree and shrub species in the occupied territories’ 260,300 hectares of forests, of which more than 15 per cent existed only in this region. Previously, 24 rare species of animals and 27 species of plants were protected in the state reserves (Basut- Chay and Garagol) and other protected areas (Arazboyu, Lachin, Gubadly, and Dashalty) before the war.

Over the last three decades, Azerbaijan has exercised no control over this region; this has created favorable conditions for the ruthless exploitation and pillage of the natural resources by the occupying forces. This illegality, coupled with the inaction of the local authorities when there are threats to the environment, such as fires, caused by the activities of the people settled in the region puts the regional environment in jeopardy.6

Illegal activities and their environmental costs

The post-Soviet leaders of Armenia have a notorious reputation for exploiting the environment to generate economic benefits3. A 2015 study titled “Environmental Crime in Armenia,” prepared by western experts with funding from the European Union, revealed the disastrous consequences of this situation for the environment of the country4. The authors reported that:

“Despite the fact that the Republic of Armenia (RA) is signatory to several international environmental treaties and conventions, environmental laws are weak, contradictory, and rarely enforced. The victims of a lax regulatory framework and environmental crime are often ordinary citizens, the economy at large and even the country’s national security. Common problem areas linked to environmental crime include RA’s vast mining sector, the logging industry and the hydroelectric sector.”

Unfortunately, the environmental crimes carried out by the Armenian authorities did not end with the forced change of government in 2018 that brought a new political elite to power. The recent initiative to expand the mining industry in southern Armenia, in total disregard of its potential impact on the local environment, is a distressing example5. It is important to note that, in the face of strong opposition from environmental activists, the government did not shy away from changing the national environmental information law, giving the authorities the right, inter alia, to withhold “information that can negatively affect the environment.” 6

The Armenian government’s pledge7 to double the country’s tree cover by 2050 sounds like a promising contribution to reversing the ecological downturn in the region8. However, a quick review of all the populistic promises that Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan has made since he took power in 2018 (e.g., the FIFA World Cup, a 15- fold increase in GDP, almost doubling the population by 2050)9 casts doubt on the true nature of this plan, which has already been postponed10.

It is important to note these facts from Armenia’s domestic politics here to illustrate what a government that does not take proper care of the environment in its own territories would do vis-à-vis the environment of a territory that it has unlawfully occupied and that is not subject to any strict oversight. The answer is self-evident: It would loot its natural resources at the maximum speed possible! This is what Armenia is in fact doing in Azerbaijan’s occupied territories.

In 2008, Armenian reporters Edik Baghdasaryan and Armine Petrosyan found out that the wood exports of Armenia had been constantly rising since the end of the Soviet period11:

“According to the Customs Department and the Statistical Office of Armenia, the volume of wood exported from Armenia has risen sharply over the last four years. During the Soviet era, the republic imported, rather than exported, wood. Today the nearly forestless Armenia exports not only wood products but raw timber as well.”

There is no doubt that the exported woods were derived not only from the Armenian forests, but also from those located in Azerbaijan’s occupied regions, or, more probably, the Azerbaijani forests were the only source. This is confirmed by the above-named Armenian reporters, who revealed in their report that “Walnut forests are being destroyed in Nagorno-Karabakh as well, but more on this at a later date.” However, they were apparently banned from speaking out about the situation in the occupied territories, as their report “at a later date” never came to light.

However, satellite imagery of the region obtained by Azerbaijan’s satellite operator Azercosmos allows us to get a clear understanding of the environmental degradation in the region. This observation demonstrates an alarming rate of deforestation, including in those areas populated with endangered tree species12. A few years ago, Azerbaijan’s ecology experts warned that:

“Upon the occupation of the Azerbaijani territories by Armenia, walnut, oak and other tree species were cut down and sold to foreign countries, and forests for cattle grazing were massively destroyed in some of the occupied regions. Some tree and shrub species, which were protected for many years such as yew-tree, Araz oak, Eastern plane, pomegranate, forest grapes, Buasye pear, box(-tree), Eldar pinewood, persimmon (date-palm), willow leafed pear, etc. are now on the edge of vanishing. From the mid-1980s to mid-1990s, the amount of forest and woodland declined by 12.5%.”

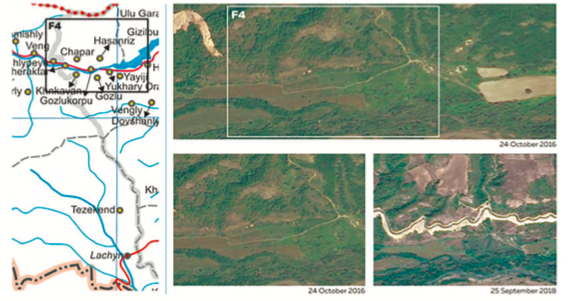

1. Satellite imagery of forest cutting for the construction of a canal near the Sarsang Reservoir in the occupied part of the Tartar district (46°30’30.882”E, 40°8’45.486”N) obtained by Azercosmos.

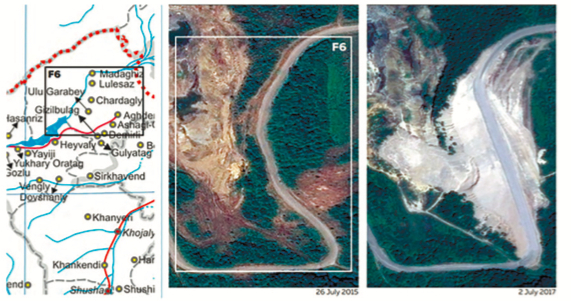

2. Satellite imagery of deforestation caused by mining activities near Chardagly village in the occupied part of the Tartar district (46°41’33.965”E, 40°14’9.393”N) obtained by Azercosmos14.

Notably, this observation was confirmed by Armenian sources. For example, a report dated September 2003 revealed that walnut trees cut down en masse in Azerbaijan’s occupied territories were being exported to Italy and Spain, adding that the claims of local authorities about the export of damaged or rotten trees sounded unconvincing15. The report showed that the exported wood was “of the highest quality, and [was] used for luxury car interiors and gun hilts,” citing a local expert who stated that “even trees in cemeteries had been torn up by the roots. Some gravestones had been damaged as a result.” It is also strange that for more than 10 years no report about the logging industry in this region has been made public; apparently, this was banned at the highest level.

Pollution of water resources and disruption of water flow

The occupied regions of Azerbaijan are also rich with water resources which are rapidly shrinking in the entire South Caucasus, thus posing a variety of challenges to the lives of the region’s people and maintenance of agriculture. While in the rest of the region local states can take some measures to ameliorate the situation, the Azerbaijani government has no access to water resources in its occupied territories.

According to some records, there are seven environmentally significant large or small surviving lakes in the occupied Azerbaijani territories that are now subject to anthropogenic impacts16.

The Sarsang Reservoir, which is under Armenian control, is now unavailable for appropriate agricultural use, thus resulting in irrigation problems, eradication of flora, and other serious environmental problems. This reservoir, located in the Nagorno-Karabakh region, is of great importance to the agriculture of the surrounding areas. Built in 1976 and containing 560 million cubic meters of water, the reservoir has the capacity to provide irrigation water for 100,000 hectares of agricultural land in six regions in Azerbaijan – Tartar, Agdam, Barda, Goranboy, Yevlakh, and Aghjabadi.

Azerbaijan has complained that the occupation regime in Nagorno-Karabakh stops the outflow from the Sarsang Reservoir to the above-named regions in summer, when people and agriculture most need water. In contrast, in winter, when the need drops, the water from the dam is released, flooding agricultural land and eroding roads. This has seriously damaged Azerbaijan’s agriculture and regional ecological situation since the occupation in early 1990s.

Describing this as “green genocide,” Azerbaijan has sought to draw international attention to the rapid deterioration of the ecological situation in the regions under occupation.10

The Council of Europe, in its resolution 2085 (2016) confirming the distressing level of water-related environmental problems in the occupied territories, stressed that “the lack of regular maintenance work for over twenty years on the Sarsang reservoir, located in one of the areas of Azerbaijan occupied by Armenia, poses a danger to the whole border region.”17The Assembly emphasized that “the state of disrepair of the Sarsang dam could result in a major disaster with great loss of human life and possibly a fresh humanitarian crisis.”

The pollution of rivers in the region is another problem that has long-since been raised by the Azerbaijani government but has only recently attracted the attention of other neighboring countries.

For example, in 2004, Azerbaijan became alarmed that “2.1 million cubic meters of polluted water is thrown down without preliminary purification in the Aras, first of all in its tributaries, running on the territory of Armenia and Azerbaijan occupied territories every day.”18 This not only destroys the flora along the river’s course, but also exterminates fish species living in its waters.

Threatened by the environmental impacts of the pollution of the Aras and similar ecological issues, Iran has recently started to express its concerns more loudly and lambasted Yerevan for the contamination of the river. A study by Iranian scientists conducted over the last few years discovered that the Aras was very highly contaminated with heavy metals19.

In November 2019, an Iranian agricultural researcher, Ahmad Baybordi, stated in a report in the Tehran Times that “Aluminum, copper, iron and arsenic have been found in the river which were 10 times the safe limits,” adding that “I have closely watched the activity of Armenian factories, I would definitely say that the industrial effluent flows into Aras and the color of water is turning green because of the high concentration of heavy metal.” 20

Another Iranian researcher explained in the same report that the source of contamination was Armenia, not the Iranian industrial units, and he therefore called on the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Iran to intervene.

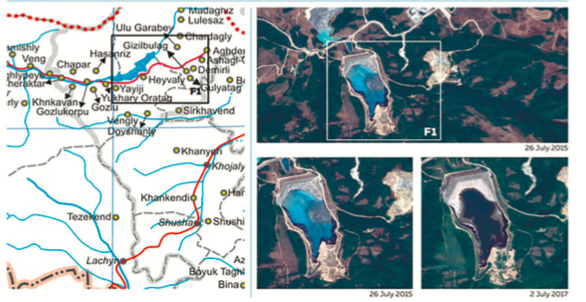

3. Satellite imagery of the tailing dump caused by the exploitation of the Gyzylbulag underground copper–gold mine near Heyvaly village in the occupied Kalbajar district (46°35’43.645”E , 40°8’34.632”N) obtained by Azercosmos. 21

The issue has been on the agenda of the highest-level talks between the two countries on several occasions, but apparently with no practical consequences. During his 2016 visit to Yerevan, Iran’s President Hassan Rouhani declared that they had also discussed environmental issues and the contamination of the Aras river, highlighting that “I hope that by the directive of [Armenian President] Mr. Serge Sargsyan, the issue will be resolved.”22Nevertheless, the above-mentioned report by Iranian scientists in 2019 demonstrates that the problem has yet to be put right.

Inaction of Armenia and its subordinate authorities in Nagorno-Karabakh in times of natural disaster

The environment in the occupied territories of Azerbaijan is also threatened by the indifference shown by local Armenian authorities with respect to the natural disasters that are undermining the region’s natural balance. This is most painfully observed when wildfires erupt in the region and spiral out of control because of the lack of an effective fire-management system.

This was well-documented thanks to the cooperation of the OSCE during the first series of massive wildfires that overran an area amounting to 163.3 km2 in the eastern part of the Armenian-occupied Azerbaijani territories in summer 2006. The fact that the Armenian authorities appeared to be rather apathetic regarding taking immediate measures to extinguish the fires in time outraged the Azerbaijani people, and they called for international intervention.

On September 7, 2006, the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution titled “The situation in the occupied territories of Azerbaijan” proposed by Azerbaijan in regard to the incidents of massive fires taking place in the occupied territories. The resolution of the General Assembly stressed the necessity of urgently conducting an environmental operation and called for an assessment of the short- and long-term effects of the fires on the environment of the region and measures for its rehabilitation.

The OSCE fact-finding fission, carried out from October 4 to 12, 2006, assessed the fires’ short- and long-term impacts on the environment in the affected territories and confirmed, inter alia, that “the fires resulted in environmental and economic damages and threatened human health and security.” The assessment also concluded that the damage caused by wildfires could partially be attributed also to the absence of effective forest fire management systems23.

This negligence, violating international humanitarian law including the Geneva Conventions of 1949, resulted in the devastation of wildlife and destruction of fertile areas in the region and transformed the entire fire-affected territories into a burned desert in less than two months. An assessment by Azerbaijani experts lamented that:

“The productive humus layer of the soil has been destroyed and it will take many years to rehabilitate this fertile layer. Many trees constituting the microclimate together with grasses and bushes have been burned as well. The area has become black. Extermination or migration to other territories of numerous fauna species caused a great, and in many cases an irreversible damage to the biodiversity of the fire-affected territories.”

Concerns relating to environmental hazards in the region have also been voiced by European institutions. For example, the Council of Europe, in its resolution 2085 (2016), noted that it “deplores the fact that the occupation by Armenia of Nagorno-Karabakh and other adjacent areas of Azerbaijan creates... humanitarian and environmental problems for the citizens of Azerbaijan living in the Lower Karabakh valley.”24

The resolution also stressed that the lack of regular maintenance work on the regional water reservoirs poses a danger to the whole border region and “could result in a major disaster with great loss of human life and possibly a fresh humanitarian crisis.”

The ramifications of environmental destruction cannot be localized

The depredatory exploitation of natural resources, the millions of tons of waste in tailing dumps saturated with heavy metals and other dangerous substances, and the massive felling of trees are literally destroying the regional environment in the occupied territories of Azerbaijan. A report prepared on behalf of the UNDP, UNEP (Regional Office of Europe), and OSCE concluded that “These areas [i.e., Nagorno-Karabakh and adjacent districts], out of the control of the central authorities, represent a major challenge for the environment and security of Azerbaijan.”25

The environmental threats posed by the destruction of the flora and fauna are not, however, confined to these territories, but also threaten the wider region of the South Caucasus. It is expected that the region will be among those most affected by climate change, even though the share of the region’s countries in global carbon dioxide emissions is insignificant. Expert estimates show that the temperature increase in the region is exceeding the global average and this is likely to be exacerbated if the deforestation is not reversed. 26

The massive exploitation of forests and other natural resources in Azerbaijan’s occupied territories thus generates an environmental threat on a wider scale. This concern is also shared by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), whose Director of Regional Office for Europe drew attention to the environmental impacts of the Armenia– Azerbaijan conflict, stating that “The environment is under serious threat as a result of the conflict. Natural pearls of the region belong to all mankind. They should be protected and no conflict should affect it.”27

Also relevant is the breach of international legal provisions that characterize destruction of the environment and pillage of natural resources as a war crime, alongside crimes against humanity and genocide. The violation of these provisions is subject to criminal liability and prosecution by the International Criminal Court. Parties in conflicts should therefore be held accountable for their disregard of international environmental law in all instances—not only when this is in line with the interests of some global powers.

Vasif Huseynov is a Senior Advisor at the Center of Analysis of International Relations (AIR Center), Baku, Azerbaijan.

The article was published on aircenter.az .

More about: