Sometime between 135,000-50,000 years ago, hands slick with animal blood carried more than 35 huge horned heads into a small, dark, winding cave. Tiny fires were lit amidst a boulder-jumbled floor, and the flame-illuminated chamber echoed to dull pounding, cracking and squelching sounds as the skulls of bison, wild cattle, red deer and rhinoceros were smashed open.

This isn't the gory beginning of an ice age horror novel, but the setting for a fascinating Neanderthal mystery. At the start of 2023 researchers announced that a Spanish archaeological site known as Cueva Des-Cubierta (a play on "uncover" and "discover") held an unusually large number of big-game skulls. All were fragmented but their horns or antlers were relatively intact, and some were found near to traces of hearths.

While caves in the upper Lozoya Valley, about an hour's drive north of Madrid, had been known about since the 19th Century, the Des-Cubierta site was only found in 2009 during investigation of other cavities on the hillside. As researchers slowly uncovered the layers inside, a startling picture of the cave began to emerge. The skulls, they argued, pointed to something beyond the simple detritus of hunting and gathering. Instead, they saw the skulls as symbolic – perhaps even a shrine containing trophies of the chase.

If correct, it would raise a tantalising prospect – Neanderthals were capable of the kind of complex symbolic concepts and behaviours that characterise our own species.

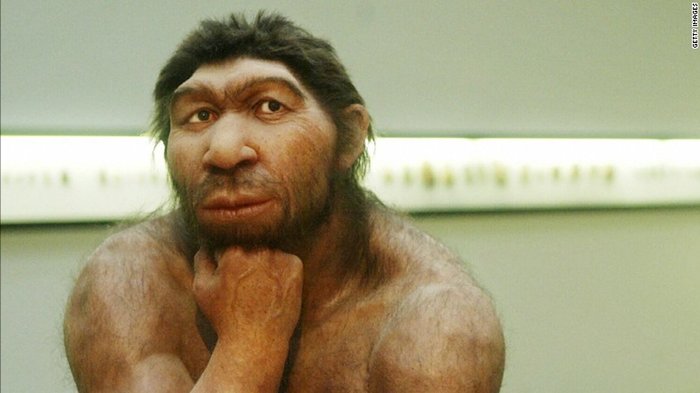

But can we really suggest Neanderthals, a hominin species that became extinct around 40,000 years ago, developed rituals centred on the skulls of their prey? Other discoveries highlight varied aspects of their culture, and some have even suggested Neanderthals produced forms of what we might call art. But the answers are far from clear.

Getting into the minds of ancient people, never mind those of a different kind of human altogether, is one of the great challenges of archaeology. Ever since the first Neanderthal remains were identified in the 19th Century, how they lived and what they thought has been a fundamental and evocative question motivating those who study them. Yet despite immense leaps in archaeology over the past 160 years, the answer remains complicated and sometimes problematic, partly because of our own preconceptions.

Neanderthals have always represented a philosophical foil to Homo sapiens – that is, to us. Initially they were the only other sort of human that we knew had existed on Earth, and even as other ancient hominin species have been discovered, they retained a special place as "the other", a kind of mirror with which to compare ourselves.

And those comparisons initially were all in our favour. The fact that Neanderthals disappeared around 40,000 years ago, after surviving for hundreds of millennia in western Eurasia, was long taken as evidence that there must have been something to explain why they "deserved" their extinction (in a scientific if not a moral sense). Consciously or not, researchers looked for evidence that Neanderthals were less successful, a beta-version of humanity destined to be replaced by our superior form. And one of the most obvious elements they focused on reflected the very thing which we believed distinguished our species from all other life on Earth: cognition.

What is cognition? In simple terms, it's how we think – our mental processes and abilities, from working out problems to our imagination. It also includes imbuing symbolic meaning in actions, objects or places.

If the research team excavating at Des-Cubierta are right, then it appears Neanderthals were capable of at least some of these higher forms of cognition.

Of course, Neanderthals aren't here to ask what they're thinking, and we can't travel back into the past to observe them. What we do have, however, is 21st Century archaeology and modern science to help us reconstruct as much as possible about Neanderthal life.

To start with the basics, Neanderthals are one of our closest-known relatives, and we last shared a common ancestor somewhere between 550,000 and 800,000 years ago, which is very recent indeed in evolutionary terms. On that basis alone, we should expect Neanderthals in many ways to be very similar to us, including brainpower. Their skulls point to cerebral volumes at least as large as our own.

But there's more to minds than brain size. While big, Neanderthal brains were apparently a bit different. Their overall shape – inferred from the inner form of their skulls – was different. This this might, therefore, mean potentially varied brain function due to how different regions of the brain seem linked to particular functions, such as analytical thought or memory.

We can also find clues at the genetic level. For example, recent research has found that tiny changes in two genes involved in neurological development have marked impacts on the human brain. One, called NOVA1, affects how neurons grow and their electrical activity, while another, TKTL1, appears to significantly increase the amount of neurons and how many folds the brain has. Neanderthals carried slightly different versions of these genes. When researchers inserted a Neanderthal NOVA1 gene into human stem cells to grow so-called "mini-brains" – in reality, clumps of differentiated cells – they found it led to altered neuron growth and the connections between them when compared with our own species. Similarly, the Neanderthal version of TKTL1 – which differed from our own by a single amino acid – may have led them to have a smaller neocortex than modern humans. This is the part of the brain involved in higher cognitive brain functions such as reasoning and language. However, some researchers have suggested that millions of modern humans may also carry the "Neanderthal version" of this gene, raising further questions about how different the brains of these extinct relatives really were.

Bones and DNA are only one way to explore what Neanderthal minds were really like. For example, recent research on their hearing has backed up the idea that Neanderthals were communicating vocally in their everyday lives. And it is archaeology, the nearest thing to a time machine, that can show us what they actually did, and therefore what they were probably talking about. Advances in archaeology over the past three decades have produced something of a renaissance in what we know, inexorably undermining preconceptions that Neanderthals were somehow lacking. From stone and even glue technology to hunting skills, bit by bit as we found out more about them, the gaps between our species have narrowed. Today there are relatively few areas that remain as clear differences.

One facet of behaviour where researchers have long looked for differences is the Neanderthals' capacity for abstract, aesthetic and symbolic thought. We have known since the middle of the 19th Century that ancient humans who lived very shortly after the Neanderthals had vanished were producing spectacular paintings of animals inside caves, finely carved figurines, and they also buried their dead with grave goods like shell beads. Despite more than a century of archaeological discoveries, we have not yet found anything truly comparable amongst Neanderthals. What has been uncovered, however, suggests their lives went beyond a simple, survival-based perspective.

One example of this is incising or engraving. Although many objects, mostly bone, have been shown through later microscopic study to have been naturally scratched or gouged, there are a number that clearly were intentionally made. One is from Les Pradelles, France, where a small piece of a hyena's thigh bone was found, bearing a series of nine parallel incisions, each about five millimetres long. It dates to around 70,000 years ago, and careful microscopic study found that the same stone tool was used, with the maker working from left to right, and progressively applying more pressure until the final line, probably because they changed the angle or shifted their hold on the tool. At the base of two of the lines further sets of minute marks had been engraved, likely again with the same tool.

What the Les Pradelles marks mean is not clear. It has been suggested that they may represent a notation or tally of some kind, but alternative interpretations exist, and there may be an aesthetic motivation here too – the secondary marks are so small that perhaps feeling them might have been as important as seeing.

So far, the most complex graphic engraving found in a Neanderthal context comes from a German site called Einhornhöhle (Unicorn cave). In this case, the bone is dated to around 51,000 years old, and came from the toe of a Megaloceros (giant deer). In addition to some of its edges being altered, with bone apparently shaved or carved off, one of the curved sides of the bone has 10 individual linear engravings. Four of these run along the base in parallel and are angled diagonally, but the other six are more complex with two sets of three intersecting each other, angled between 92-100 degrees. The effect is a repeating chevron pattern, and while once again assessing any precise meaning is impossible, the Einhornhöhle piece seems less likely to be a simple tally marker.

Engraved objects, or in the case of the Gorham's Cave in Gibraltar where a "hashtag" has been etched into a raised section of the stone floor itself, are rare among Neanderthal artefacts. Less than 10 clear examples exist. But there is more abundant evidence that Neanderthals had an interest in colour. Mineral pigments, in colours ranging from black through red, orange, yellow and even white have been found at over 70 sites. In some contexts, there is not only significant amounts, such as the more than 450 pieces of pigment from layers at Pech de l'Azé, in the Dordogne, southern France, but also clear evidence that these pieces were being processed and used. Some show scratching and grinding marks, while others have traces from being rubbed across softer things. Sometimes Neanderthals seem to have even selected particular mineral outcrops for the intensity of the pigment, and remarkably, also combined and mixed them: red with yellow to produce orange.

While we can only guess what most of the colour was being used for – and one type of black pigment, manganese dioxide, can also act as a chemical firelighter – there are some remarkable discoveries of "painted" objects. They include an orange mix combined with sparkly iron pyrite (fool's gold) on a shell and red pigment on the outer surface of a small fossil shell. Another mixture of pigment was also found on an eagle's talon, one of eight from Krapina, Croatia. And tantalisingly, there is also some evidence from the collapsed cave of Combe Grenal, near Domme in France's Dordogne, that the Neanderthals who lived there seem to have preferred different colours over time. The pigments found at the site changed through the layers, and while there is no obvious explanation for changes in local mineral source availability, there is a rough correlation with changes in stone tool types, which might point to different cultural traditions in pigment use.

The Last Neanderthal: But is it Art?

In recent years, there have also been new claims that Neanderthals applied red pigments to cave walls. Studies in three Spanish caves long known to contain prehistoric paintings analysed some of the concretions covering red patches, a red line and a negative hand print. The results ranged from minimums of 55,000 to 64,000 years old, well beyond any accepted age for the presence of Homo sapiens in Iberia. More recently red pigment pieces have been found within one of these caves – Ardales, in Málaga, Spain – within layers that contain Neanderthal-typical stone artefacts, that can be dated to around the same time as when red pigment was smeared and blown onto stalagmite formations. But researchers have still to find a chemical match between the pigment and the paintings.

In recent years, there have also been new claims that Neanderthals applied red pigments to cave walls. Studies in three Spanish caves long known to contain prehistoric paintings analysed some of the concretions covering red patches, a red line and a negative hand print. The results ranged from minimums of 55,000 to 64,000 years old, well beyond any accepted age for the presence of Homo sapiens in Iberia. More recently red pigment pieces have been found within one of these caves – Ardales, in Málaga, Spain – within layers that contain Neanderthal-typical stone artefacts, that can be dated to around the same time as when red pigment was smeared and blown onto stalagmite formations. But researchers have still to find a chemical match between the pigment and the paintings.

In many ways, applying the word "art" to Neanderthals is tricky, because it comes with a lot of interpretive baggage. For example, we might assume that such objects were finished creations, and contain symbolic information. Instead, it can be helpful to focus on how they were actually engaging with materials, and talk about "aesthetics". What Neanderthals' engravings and pigments have in common is an intention to alter how surfaces were perceived, whether visually or in a tactile way. The Krapina talons, for example, have tiny areas of polish, as if they rubbed up against other hard materials, perhaps each other. While one interpretation is that they could have been worn as a necklace, it's just as possible that lustrous and perhaps painted talons might have been strung as a rattle, making them a visual and sonic aesthetic experience. But such assumptions require care – we may never know if these were made and kept by individuals, or intended to be displayed and experienced by many others.

Material creations that undoubtedly did involve a community interaction do however seem to be something Neanderthals were capable of, evidenced by a spectacular announcement in 2018 involving a cave near Bruniquel, in southern France. Discoveries at the site go back to 1987, when a teenager keen on caving found a tiny cavity from which a breeze was coming, as if the hill was exhaling. After three years of patient digging and crawling, one day he broke through into a system of large chambers, some with beautiful shallow pools. One of which, some 300m (984ft) in, contained a truly remarkable construction. What had seemed initially to be some kind of dam made of fallen stalagmites turned out to be a structure made up of snapped off pieces, obviously human-made, but by people who'd left no traces except a few burnt pieces of bone. In the mid-1990s radiocarbon dating pointed to a remarkably ancient age, beyond the technique's then-limit of 45,000 years. It was only after dating of calcite deposits over the stalagmites using a different method that measures the ratios of uranium and thorium in the rock, reported in 2016 that the true antiquity of the rings became apparent – 174,000-176,000 years old. The only conclusion to be drawn is that the creators must have been Neanderthals.

And Bruniquel is remarkable: over 400 stalagmite sections collectively weighing some two tonnes were selected by size, and arranged into two rings, the largest more than six metres (20ft) across. Two piles of stalagmites lie inside, and two more outside. There is abundant evidence of burning, potentially to help in fracturing the columns. And all this is no sloppy job: in places the rings are made up of four layers, sometimes with pieces leaning up against them. In some areas, inside the walls there are several pieces balanced on top of each other, looking like tiny columns and lintels.

Bruniquel undoubtedly contains something built by Neanderthals, but what? An explanation as some kind of habitation or regular living space seems unlikely. The cave system so far does not appear to have an entrance close to the chamber, which is set deep into the hill. It's far more remote than any other Neanderthal living sites, which tend to be at cave mouths or only a few tens of metres inside.

The remoteness of the chamber also means that there would have needed to be permanent illumination, which would not only have meant an extraordinary expenditure of time and energy during a cold phase of the climate when trees were not abundant, but also led to a permanently smoky environment. And most strikingly, so far there are no actual stone tools. Pawprints of cave bears who used the chamber long afterwards have likely scuffed away Neanderthal footprints, but if this had been an occupied place, there should still be some debris from their daily lives. But beyond the 18 fire "hotspots" and piece of burnt bone, no artefacts, or any other remnants have yet been found.

The site is still being studied, and it's possible artefacts might be hidden beneath the flowstone floor that has formed as water has slowly dripped into the cave. Magnetic signals do suggest there are hearths hidden beneath it. But, for now, it is hard to see how the Bruniquel rings had a practical purpose. Instead, perhaps this labour-intensive construction had another kind of significance for the Neanderthals who built it.

Let's return to the mystery of the skulls in the dark at Cueva Des-Cubierta. It also demonstrates the complexity in interpreting unusual remains left behind by Neanderthals. The 80m long (262ft) cave itself, which ranges from 1m (3.3ft) to 4m (13ft) wide, formed at least half a million years ago, but the archaeological deposits date from somewhere between about 135,000 and 50,000 years ago. After years of painstaking work, initial results began being reported in 2012, including the discovery of a few fragments from a Neanderthal child aged between 3-5 years old. This is a significant discovery in its own right – every new skeletal piece we add to the record for this species is precious. As the excavation continued, with the animal skulls and hearths being uncovered, the notion that Des-Cubierta might be some kind of place for burial rituals emerged.

While the excavation team suggested it might represent burial offerings or a hunting shrine, for other researchers, Des-Cubierta does not contain clear indicators beyond "everyday" behaviour. First, later analysis found that the hominin remains, mostly of a jaw, were originally from the layer overlying that with the animal skulls. Second, there is no obvious spatial pattern to the skulls, beyond some being near traces of hearths. Third, the layer the skulls and hearths were in built up over a considerable time, covering some 2m (6.6ft) in depth, which would require a very long-term ritualised use of the space. And finally, an "ordinary" explanation does exist: cut-marks and smashing shows that the brains, eyes and tongues were being removed for food. It seems that hunted animals were initially being butchered elsewhere, potentially just outside the cave, and then the skulls along with some other bones were brought inside to be further processed by hearths. Once the juicy bits within the skulls were obtained, there was no reason to further smash them up, and perhaps the blocky, cobble nature of the layer meant that they survived in more complete form than typical.

But why would the Neanderthals bother to carry these heavy skulls inside? We know from discoveries at other well-preserved sites that Neanderthals separated different stages of their tasks between places, both across the landscape and within caves. For example, finds at Abric Romaní in Spain and Grotta Fumane in Italy show that, when butchering animals and birds, sometimes different body parts like wings or skulls were processed in different areas. Something very similar seems to explain the pattern at Des-Cubierta, and would support the general cognitive implication that Neanderthals carefully organised their time and activity.

So maybe Des-Cubierta doesn't require that we invoke an explanation involving skull trophies. But that doesn't mean that hunting and animals didn't hold social significance for Neanderthals. An intriguing possibility that researchers are paying increased attention to is that Neanderthals may have seen the creatures around them in relational terms, rather than as mere resources.

We can see something similar operating in the tendency for chimpanzees to sometimes, instead of hunting, keep small animals apparently as "pets", even though typically the creatures don't survive long. For Neanderthals, our closest evolutionary relations who were on so many levels curious and highly intelligent, it might have made perfect sense to perceive both their prey and other predators as fellow beings, and part of their social world.

Even if the Des-Cubierta skulls were not trophies, perhaps their presence inside the cave, still relatively whole, meant something to Neanderthals, and in a way that manifested the presence of the incredible, powerful animals they shared their life with.

More about: