| The Analytical Group of AzVision.az |

The Liquid Problem | Long Read// There is no ‘lack of water’ problem per se, there is one of mismanagement |

|

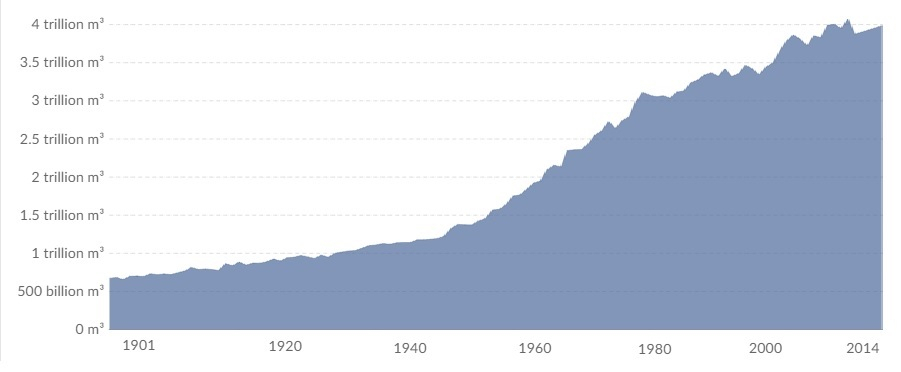

H umanity did not think of water as an EXHAUSTIBLE resource until recent decades, because we have used it as an INEXHAUSTIBLE, renewable one for centuries. After all, how can we run out of water?! The issue sounds incoherent at first: mankind returns the water back to nature once they have used it. We do not burn it unlike oil. Water does not leave planet Earth. It merely goes round in an endless circle. So, why should it diminish?!This pattern of thought prevents us from understanding the problem at hand fully. The reality is quite different. True, the volume of water on Earth is constant , and it indeed does not decrease with use unlike oil. However, due to uneven distribution, the availability of this vital resource is dwindling where it is most needed . The global population grows by 1.1 percent each year, which translates to 84 million people . Drinking water resources must also increase by 60 million cubic meters annually to provide for such growth. This is such a great number that even if we do return the water we use back to nature, it does not have enough time to ‘digest’ it and replete its resources. For instance, groundwater renewal rate is only 1% per year . Therefore, the reserves are gradually shrinking. |

||

|

||

| Global water consumption growth dynamic. Source: Global International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme (IGB) |

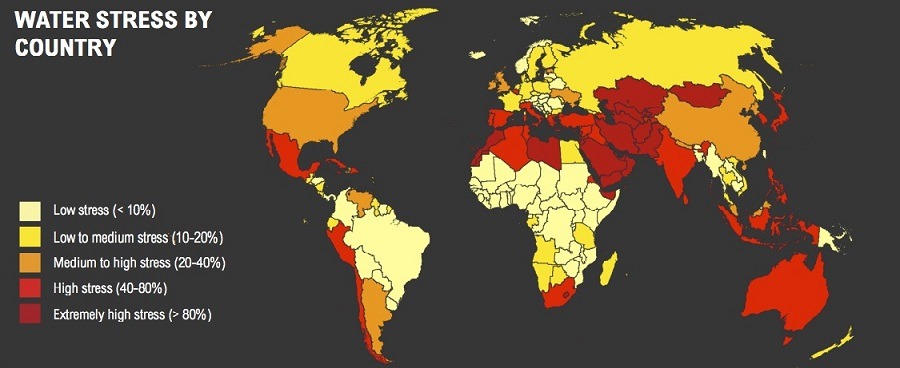

While depletion is one hand of the problem, pollution is the other. Rivers and lakes are held back from the balance as they get contaminated to unsuitability. While there are 750 cubic meters of water per capita at the moment, the number is to drop to a mere 450 by 2050. 80% of global population will fall under a mark, defined as ‘water scarcity’ by the UN. Various regions will experience the aftermath of the problem differently due to uneven distribution of water resources around the globe. Denis Sorokin, head of regional information centre at the Scientific Information Centre of the Interstate Coordination Water Commission of Central Asia in Uzbekistan says in his article for AzVision that Europe and Asia, which account for 70% of world’s population, contain only 39% of global river water reserves. Only 7% of the total water supply worldwide is concentrated in Europe, with almost 20% of global population. While the vicinities of several large rivers around the world remain practically unpopulated. Water Stress The term ‘water stress is commonly used to describe the problem. It refers to the water yield to water demand ratio in a certain country. An exceeding demand translates to a water stressed country. The research conducted in Azerbaijan forebodes that we, too, will enter the ranks of such states in 2040. |

|

|

||

| Global water stress map. Source: World Resources Inst. |

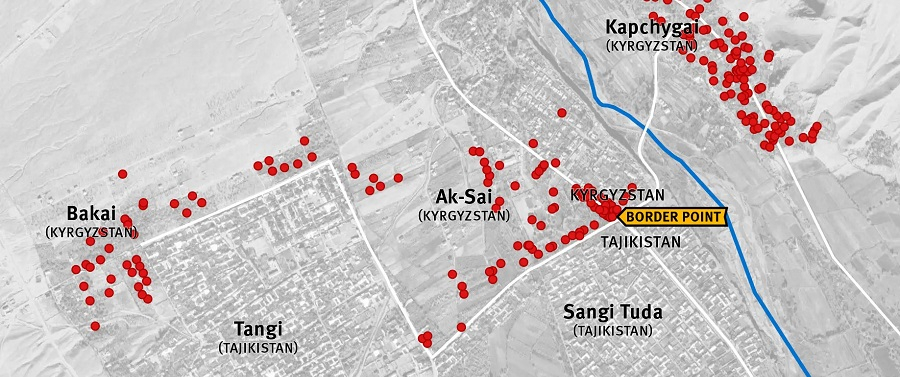

It is absolutely crucial to understand the problem on a regional scale. No country alone can shoulder the water problem, because unlike countries, the water cycle in nature is boundless. The biggest rivers of the world flow through territories of several countries, not one. Inadequate water management in one makes the neighbours suffer as well, which might lead to political tension, even conflicts at times. The world has seen over 500 ‘water’ confrontations over the past 50 years, 20 of them escalating to hostility. Ban Ki-moon, former UN Secretary General, officially admitted: ‘Fresh water may become the main cause of regional wars in the immediate future’. Three billion people across 50 countries may be forced to live in zones of armed conflict due to water shortage. |

|

|

||

| Disputes over water were one of the main reasons behind the September 2022 border conflict between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan |

What

about the situation in the Caspian countries? Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan

has the severest water problem in the South Caucasus because most of the

precipitation arrives from the Atlantic Ocean. Türkiye and Georgia, which are

both to the west of Azerbaijan, receive more of it. Experts warn that water

resources in Azerbaijan will diminish by 15 to 20% by 2040.

While

going deeper into the subject, AzVision revealed an unexpected fact: we

do not know how much water exactly we have! Zakir Eminov, Doctor of

Geography and Director of ANAS Geography Institute says, the water resources in Azerbaijan were

calculated back in the 1970s. The last book on the matter was published in 1985:

‘Which makes them the estimations of late ‘70s and early ‘80s. We must

establish new commissions and recalculate. Managing anything requires

measuring it first. But we do not know how much water exactly we have

currently.’ |

|

| Zakir Eminov: ‘Citizens need around 500 litres of water a day’ |

The

population in Central Asia is over 75 million and the number is expected

to exceed 100 million by 2050. The summers in the region are getting

hotter every year, which accelerates desertification. These factors

boost water consumption among both the population and agriculture. Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan

is one of the countries that suffer the acutest water problem in Central Asia. The

water demand in the country will go up by 46% by 2040, while World Bank

forecasts the water resources in Kazakhstan to decrease from 90 to 76m³ a year

by 2030. This translates to a water shortage of 12-15m³ per year, that is, 15%.

Aizhan

Skakova, candidate of geographical sciences,

environmentalist, an ecology expert at the Majilis of the Republic of

Kazakhstan points out in her article for AzVision

that shortage of water resources in Central Asia is one of the main

limiting factors for the development of regional countries. The growth of

water consumption leads to competition for water at the regional and local

levels among various sectors of the economy. The need to take care of their

food and energy security will increase the water requirements and tension over

water in the region. |

|

|

||

| The water in Syr Darya is on the decline |

Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan

ranks 34th among the most water stressed countries around the

globe. Experts warn that the drinking water shortage will go as high as 7

billion cubic metres in 2030. The amount of water per capita has decreased

by 48% in the last 15 years, dropping from 3,048 cubic meters (2008) to

1,589.

Only 10% of water resources take shape on the territories of the country, which translates into great dependence on waterflow arriving from neighbouring countries. In the last 50 years, Syr Darya and Amy Darya – the two largest rivers in the region – have lost 20% of their water supply.

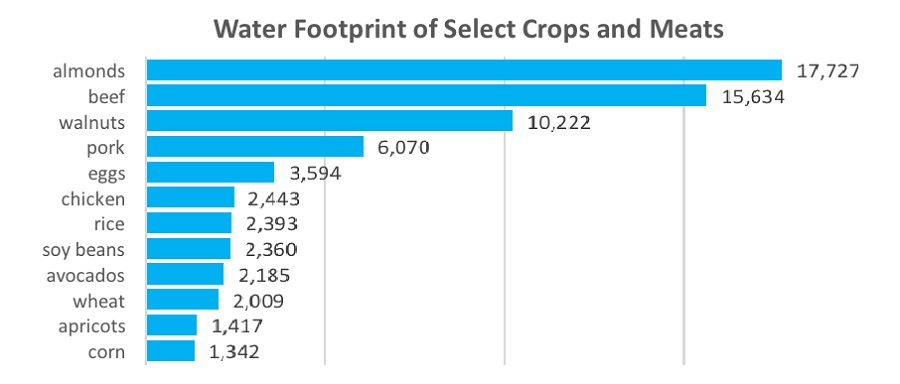

Thirst Equals Hunger The main point remains that water does not only cover people’s domestic

needs. Agriculture accounts for the biggest portion of it. Over 90%

of water withdrawn from river basins in Central Asia is used for

agriculture. Animal husbandry is the second largest ‘water spender’. Scientists

at the University of Twente in Netherlands have calculated that producing a

kilogram of beef needs 15 thousand litres of water. One kg of pork accounts

for 6 thousand, and one kg of chicken for another 4.3 thousand litres.

We are certainly not talking of the water these animals drink: we must also

grow their feed… The plants need no less: growing a kilogram of legumes or rice requires

4 thousand litres, a kg of wheat another thousand litres. A kilogram of

potatoes translates to a hundred litres of water. Basically, 2,400 litres of

water goes into making one hamburger. |

|

|

||

| Water used to produce a kilo of various foods, in litres. |

Clearly, water scarcity does not only come down to thirst, but also

hunger. And agriculture must be the first field to save. Water’s Number One ‘Enemy’ One of the main reasons behind water shortage is the ever-growing

demand for food due to the boost in world population. Around 80% of

water resources are spent for agricultural needs.

Garib Novruzlu, deputy director at

the Agricultural Research Centre under the Ministry of Agriculture, PhD in

Agrarian Sciences says in his interview to AzVision.az that the field is in

need of fundamental infrastructural changes: ‘The water from sources is mainly

delivered through earth ditches. Say, there is a kilometre from source A

to point B, which would take the water 15-20 minutes at most if

delivered through concrete canals, whereas it takes the water an entire week

(!!!, editor’s note) to reach its destination point. And that is if we are

lucky enough to have rapid waters… |

|

| Garib Novruzlu: ‘Fundamental changes must be introduced in water infrastructure’ |

It is hard to

escape the conclusion that if the water infrastructure is not updated

fundamentally, applying new technologies in the fields will not yield great

effect, whereas applying the new methods after concreting the canals

might completely change the picture. For instance, bedropping a hectare of a

grain traditionally requires 1,200-1,500 cubic meters, that is 1,55 tons of

water, while 30 to 50 tons of water suffice to drip irrigate the same

hectare. The difference is about 30 times! The same problem

persists in Kazakhstan. Ayjan Skakova, candidate of geographical

sciences, environmentalist, an expert at the Majilis of the Republic of

Kazakhstan, says in her interview to AzVision that the efficiency of

irrigation systems in the country does not exceed 0.45-.055, which

translates into 50% of irrigation waters lost. The number goes up

to 40% in Uzbekistan as well, while agriculture is the driver of the Uzbek

economy. The country owes 30% of its economy to this field.

Only 16% of irrigated arable uses drip

irrigation technologies and sprinkler systems in Kazakhstan. Basically,

most of the irrigation waters seep into the soil. This requires changing

the policy of state support in irrigated agriculture. It must be rendered to

only those, who implement water-saving technologies. |

|

|

||

| Can cactus be a traditional source of food for our region? Let’s not haste to say ‘no’! |

What are Some

Other Ways? There are not

plenty of options, in fact. The systemized list of all the advice given

by the experts we interviewed is as follows: ·

Saving

water ·

Recycling

wastewaters ·

Desalinating

sea water ·

Cultivating

salt tolerant plants in saline soil through genetic technologies. These can be

irrigated with salty waters, which substantially saves fresh water. ·

Mass

transitioning to drip irrigation ·

Transporting

glaciers to regions in more need of water ·

Drilling

deep wells. Each of these

methods poses its unique advantages and disadvantages. Rovshan Abbasov,

Head of Geography and Environment Department at Khazar University, Ph.D. in

Geography recalls an interesting conversation in his interview to AzVision.az.

‘I was posed a very interesting

question by a Mexican professor of agronomy. ‘How come you do not grow cacti

for food?’, he asked. He went into detail explaining how Mexico covers most

of its food demands by cactus, which does not require much water. As I

objected that cacti were not traditional for Azerbaijan, he reminded me

that both tomatoes and potatoes were once brought from Mexico, and they were

also not traditional at the time.’ |

|

| Rovshan Abbasov: |

Well, are we ready to see cactus

dishes on our dinner tables? Let’s not be too hasty to answer. Another one of our experts insists that there is no other plant that can

replace wheat both in and outside Azerbaijan. ‘Maybe there will be one in

50 to 100 years, but it seems unrealistic for now.’ When it comes to

desalinating seas, the salinity of the Caspian Sea is much lower

than that of the ocean, which translates to less costs to make it drinkable.

Azerbaijan has already started moving in this direction and it will play a

positive part on both water and food security in the country. In a broader sense, desalinating

a litre of water costs 2.5 USD, that is around 5 manats. Although it might

suffice to meet some of the important needs around the household, the method

should not be widely relied upon in agriculture. If irrigating a hectare of

land costs 3,000 dollars, the product will end up having a phantasmagorical

price tag. Neighbour, have you

got running water?

The main path to solve the water

problem runs along regional cooperation. For example, Georgia is expected to

build five additional dams on the Kura River alone, while Armenia is planning

to build around 120 on smaller rivers within the next 10 years. This might

leave a serious imprint on Azerbaijan’s food and water security. A fairer

distribution of waters in the Kura River must be achieved both within

international conventions and through direct negotiations. There is an

international convention on managing transboundary rivers, which envelops

issues such as ecosystems of these rivers, flow preservation, and equal

distribution of water among countries. |

|

|

||

| Considering the interests of neighbouring countries is crucial while exploiting transboundary rivers |

The Samur river currently covers

most of the demand in the Absheron Peninsula, including Baku. However, the glaciers in the Samur

basin have melted, the water in the river has naturally decreased, as the

demand for it continues to grow. Less water is expected to arrive in Azerbaijan

from the Samur River within the existing contracts. We might need to revise

those contracts. The Caspian basin shrinks by 70 cm a

year on both Kazakhstani and Azerbaijani shores, which is partly caused by reduction

of water in the Ural River. There are 300 reservoirs with a total

capacity of 4.9 million cubic meters on the river, which take most of the

water upstream. The average water volume in the river used to stand at 9.4

billion cubic meters, whereas it has now plummeted to 5.7. Kazakhstan and

Russia are running joint projects to prevent shallowing of the river. We have thus arrived at a conclusion

that escaping water stress and problems in can bring along requires regional

cooperation and integration of water management systems in these countries.

|

|

|

||

| The fate of the Aral Sea proves that there is no one who can shoulder the water problem alone |

Central Asia has been striving for

cooperation in the field lately. In 2023, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and

Kyrgyzstan agreed on constructing a hydropower plant on the Narin River. There

is also the Interstate Commission for Water Coordination in the region,

albeit with no leverage and little authority. Countries around the Aral Sea

have established the Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM). But

all these do not suffice and there is a need for a more comprehensive

coordination. Liquid Logic Guided by the principle of justice,

water resources in the regions must be distributed equally, considering the

interests of all parties. But it is easier said than done. The main point

is that energy resources, such as oil, gas, and coal, have a price tag, water,

on the other hand, is free. This approach does not satisfy the countries with

abundant water. Their rhetoric demands that if some are selling oil gifted

to us by nature for money, why should water, also provided by nature, be free? There are certainly dozens of arguments

that render such rhetoric meaningless. But we must first and foremost realize

that lack of water is not the culprit. The real problem is the improper

management of it. It is a problem that can only be solved jointly.

The

alternative is to fight for water. In other words, there is no alternative. We

must simply learn to manage water resources together. That’s it. |

|

-1728294271.jpg)

-1680010126.jpg)