Many experts agree that the drinking water problem might lead to a global war in the future. They are also suggesting a variety of methods to save fresh water to avoid this horrendous scenario. Rovshan Abbasov, Head of the Geography and Environment Department at Khazar University, PhD in Geography, explains that climactic and anthropogenic factors have joined forces to breed the drinking water problem. He sees the way out in primarily applying more efficient water management.

- How real are the statements on the severity of the water problem? Can it be a speculation of sorts?

‘This is the reality of our time. The world population is growing rapidly and with it the demand for both drinking and irrigation water. More than 80% of food grown in the world is produced through irrigation, which translates to a greater demand for water to ensure food security and a greater exploitation of freshwater sources. This, in its turn, leads to conflicts and a lack of resources. The world population is expected to grow until 2050, which leaves less water resources per capita. This shall give rise to new conflicts.

The major rivers in the world pass through several countries. For example, the biggest ones form in the neighbouring states. Incompetent water management in those countries takes a toll on us, too. Massive water loss and unaccounted water withdrawals in the territories of those states gradually reduce transboundary flow to Azerbaijan.

The same example applies to other countries, such as Ethiopia and Egypt, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, Syria and Türkiye… There are too many. This calls for greater international cooperation.’

- Is the drinking water problem the product of natural causes or anthropogenic?

‘Both play their part. The population growth requires the employment of modern technologies. Water management, on the other hand, is one of the most difficult ones there is, which involves, the distribution and timely delivery of water resources to the customer. Gaps in this area manifest themselves very quickly.

On the other hand, climatic changes are also shrinking drinking water resources on Earth. As the ocean level rises, so does the precipitation in coastal regions. This is not a drinking water problem per se, but a dangerous water matter. In other terms, the water which was considered drinkable until now poses great threats to coastal terrains, such as landslides, floods, natural disasters… This is accompanied by water shortages in inland countries. Azerbaijan is also considered one. The water resources in countries far from the ocean are greatly affected by climatic change. Azerbaijan, for instance, is prognosticated to have 15-20% less water resources by 2040.

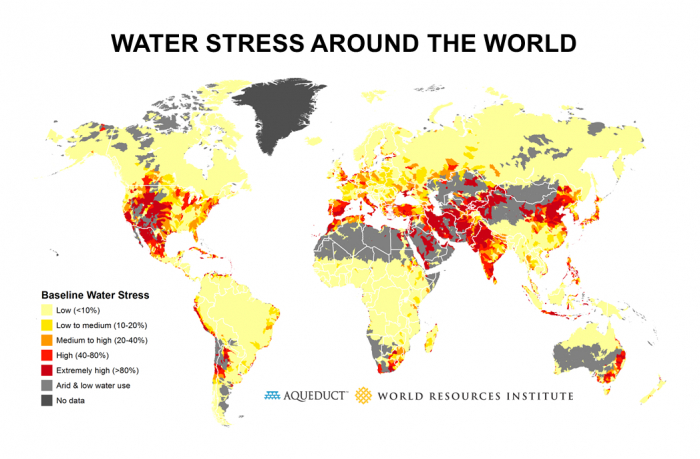

All these processes are aggravating the water stress around the globe. So, what do we mean by ‘water stress’? It is the ratio of water yield of sources within a country to its water demand. If the demand is greater than the yield, the country is considered water-stressed. Some of such countries are Israel, Kuwait, Lebanon, and Saudi Arabia. Research in Azerbaijan indicates that we are going to have higher water stress, thus joining their ranks by 2040.’

- What would you say about the water potential in Türkiye and South Caucasus in the context of upcoming crises?

‘Population grows in all countries, who are trying various means to ensure food security. I would not want to go into the political side of the issue, but we have all witnessed how the Ukraine-Russia conflict affects food security in other countries. Therefore, they all want to establish their independence in terms of food supply. These efforts boost the demand for water dramatically.

This is exactly why Türkiye is hard at work building various dams and reservoirs. They are trying all they can to preserve the waters of rivers flowing through their territories without letting any flow to neighbouring states. The same applies to Armenia and Georgia. Georgia is expected to build five additional dams on the Kura River alone, while Armenia is planning to build around 120 on smaller rivers within the next 10 years. This leaves a serious imprint on Azerbaijan’s food and water security. We must aim at solving the issue both within international conventions and through direct negotiations, which can be much smoother with brotherly Türkiye than with Armenia or Georgia. But these talks must be held for a fairer distribution of waters in the Kura River. There is an international convention on managing transboundary rivers, which envelops the ecosystems of these rivers, flow preservation and equal distribution of water among countries.

Azerbaijan is also experiencing problems with the Samur River, which currently covers most of the demand in the Absheron Peninsula, including Baku. The river is getting depleted, as the glaciers in the Samur basin have melted, the water in the river has naturally decreased, as the demand for it continues to grow. Less water is expected to arrive in Azerbaijan from the Samur River within the existing contracts. So, what must we do? We must have a very flexible and modern water management system in place.’

- What are some other options for solving the drinking water problem?

‘We are exploring a variety of opportunities in modern water management. One of the studied fields is the desalination of seawater. Israel, Lebanon, Syria, Saudi Arabia, and Kuwait are already covering a large portion of their demand through desalinated seawater. Azerbaijan is a bit luckier in this regard because the salinity of the Caspian Sea is lower than the ocean level. This translates to less costly projects. I personally am very hopeful on supplying the Absheron Peninsula with desalinated seawater in the future. Azerbaijan has already stepped onto this journey, which will favourably impact our water and food security.

There are many other alternatives. We are using modern technologies, such as drip, underground, and sprinkler methods, to reduce the demand for irrigation water. These methods substantially reduce water losses, up to 80% at times. We can thus produce more food with less water.

I was posed a fascinating question by a Mexican professor of agronomy. ‘How come you do not grow cacti for food?’, he asked. He went into detail explaining how Mexico covers most of its food demands by cactus, which does not require much water. As I objected that cacti were not traditional for Azerbaijan, he reminded me that both tomatoes and potatoes were once brought from Mexico, and they were also not traditional at the time.

What I would like to offer is to start cultivating agricultural species and varieties that depend less on water. Leading institutions around the globe, international organizations and states alike are taking significant steps in this direction.

Water losses are yet another danger. 50% of water supplied to the fields is lost in most countries, including Azerbaijan. Avoiding this problem requires shifting from earthen channels to pipe methods and applying more contemporary irrigation technologies, as I mentioned above, thus using a water management system where we know the value of every single drop of water.

Icebergs are also promising for their large water reserves. The world is now experimenting with transporting them to coastal countries. We can also be somewhat hopeful about the opportunities available in this method.

Sahil Isgandarov

AzVision.az

More about: