The answer could quite possibly be yes. "Meteorological factors certainly play an important role in determining the global range of the virus-transmitting Aedes (aegypti species of) mosquitoes and how competently they can transmit a virus," said Andrew Monaghan, a research scientist at the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research.

El Nino, which is characterized by warming waters in the central and eastern Pacific Ocean, typically brings warmer temperatures and shifting precipitation patterns to South America and can create conditions that help mosquito populations, and the diseases they can transmit, thrive.

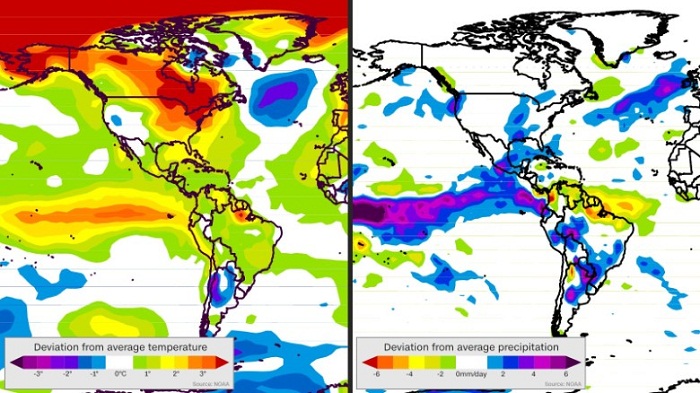

Map on left shows how the average temperature during the last 90 days is different from the average temperature of the same 90 days from 1981 to 2010. On the right, the rate of precipitation during the last 90 days is compared to the rate from the same period from 1981 to 2010.

The current El Nino episode began in mid-2015 and is tied with the 1997-98 El Nino for the strongest on record. Accordingly, the impacts from such a strong event are being felt far and wide, and this includes heavier than average rainfall in parts of Uruguay, southern Brazil and Paraguay. Massive flooding at the end of 2015 displaced 150,000 people in the region. These large amounts of fresh, standing water are ideal mosquito breeding grounds and certainly have contributed to the rapid spread of the Zika virus.The United Nations specifically mentions that El Nino can cause an "increase in vector-borne diseases including dengue, chikungunya and Zika virus due to increased mosquito vectors."

Drier conditions do not necessarily mean a region will avoid a rapid spread of the disease, however. Northern Brazil, Venezuela, Guyana and Suriname have seen the Zika virus locally transmitted in recent months, despite El Nino bringing them drier-than-normal weather. Drier-than-normal conditions during a time that is usually quite wet bring more people outside for activities, which in turn leads to greater transmission of vector-borne diseases. In addition, El Nino fueled drought in northern Brazil has led to stockpiling of water, according to CNN`s Shasta Darlington in Recife, Brazil. These stockpiles of freshwater provide ideal breeding grounds for the mosquitoes, according to Dr. Bill Reisen, at University of California, Irvine.

Warmer temperatures also make it easier for the disease to flourish. According to the United Nations, increased temperatures can "enhance reproduction and transmission" of viruses such as Zika. Reisen said that under warmer temperatures, "There are more mosquitoes, they bite more frequently, and they can transmit the virus earlier in their life cycles." Warmer temperatures can also lead to longer mosquito seasons, which begin earlier and end later during warmer years.

El Nino has raised the temperature all over the world, leading to a record-smashing global temperature in 2015. South America was certainly feeling the heat, as 2015 was the hottest year the continent has seen since records began 106 years ago. Over the past 90 days, as El Nino has reached its peak; all the Zika-affected countries have seen well above average temperatures.

El Nino is almost certainly playing a role in the Zika virus "spreading explosively," as the head of the World Health Organization said on Thursday. It will likely continue to spread as these conditions continue to create an environment where the mosquitoes can thrive.

Once the temperatures rise in spring and summer in the United States, the Aedes aegypti mosquito that is spreading the disease will likely find more suitable conditions in the north to breed. El Nino has brought an expected wetter than average winter to the southeast United States, where the species is already known to exist.

More about: