The US researchers named it after the Greek word for amber ("elektron") - the fossilised resin of long-dead trees.

Their discovery appears in the journal Nature Plants.

The two flowers were among 500 fossils collected on a 1986 field trip by Professor George Poinar of Oregon State University.

Prof Poinar is a renowned entomologist and most of these specimens were insects. But after nearly 30 years working on the bugs, his eye settled on the flowers.

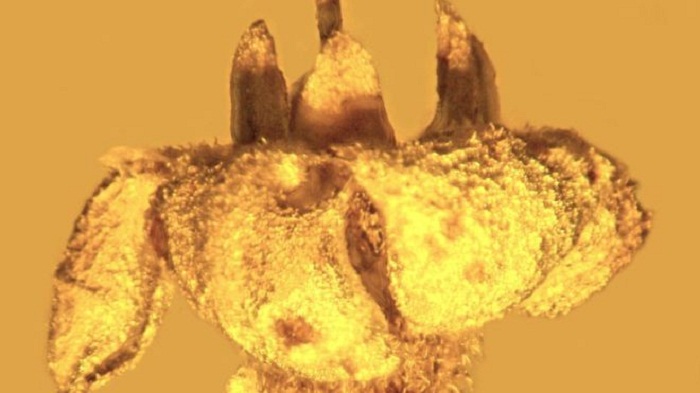

They were remarkably complete - unlike most plant fossils found in amber, which are usually just fragments.

In 2015, he sent high-resolution photos to Professor Lena Struwe at Rutgers University.

Probably poisonous

"These flowers looked like they had just fallen from a tree," said Prof Poinar. "I thought they might be Strychnos, and I sent them to Lena because I knew she was an expert in that genus."

Prof Struwe set about comparing the physical structure of the flowers to all 200 known Strychnos species, combing the collections of multiple museums and herbaria.

"The characters mostly used to identify species of Strychnos are flower morphology, and that`s what we luckily have for this fossil," said Prof Struwe.

"I looked at each specimen of New World species, photographed and measured it, and compared it to the photo George sent me. I asked myself, `How do the hairs on the petals look?` `Where are the hairs situated?` and so on."

For the animals of the late cretaceous, S. electri was probably not very good eating.

"Species of the genus Strychnos are almost all toxic in some way," said Prof Poinar.

"Each plant has its own alkaloids with varying effects. Some are more toxic than others, and it may be that they were successful because their poisons offered some defence against herbivores."

The most famous such alkaloid, strychnine, is a toxin that once formed the basis of many rat poisons - as well as being one of Norman Bates`s murder weapons in the Alfred Hitchcock movie Psycho.

But these plants also fall within the "asterid" family, which includes more than 80,000 flowering plants including many of the ones humans eat, from potatoes and mint to sunflowers and coffee beans.

The new discovery is a crucial addition to the fossil record of this family, which is very poorly understood.

More about: