At several overlapping meetings in recent weeks — in Hanover, Rome and Brussels — EU leaders and their most trusted aides have discussed how to mount a common response to Brexit, which would be the bloc’s biggest setback in its 60-year history.

More than a dozen politicians and officials involved at various levels have sketched out to the Financial Times the ideas for concerted action to “double down on the irreversibility of our union” — as well as the many internal divisions that stand in their way.

Rather than attempt a sudden lurch to integrate the eurozone, Chancellor Angela Merkel of Germany and President François Hollande are instead eyeing a push to deepen security and defence co-operation, a less contentious initiative that has appeal beyond the 19-member euro area.

Foremost is the challenge of managing expected financial and political turmoil in the aftermath of a Brexit vote. Beyond the first statements to reassure markets, officials expect a special gathering of EU leaders — without Britain — to discuss the bloc’s response. A summit of all 28 leaders is already scheduled for June 28-29.

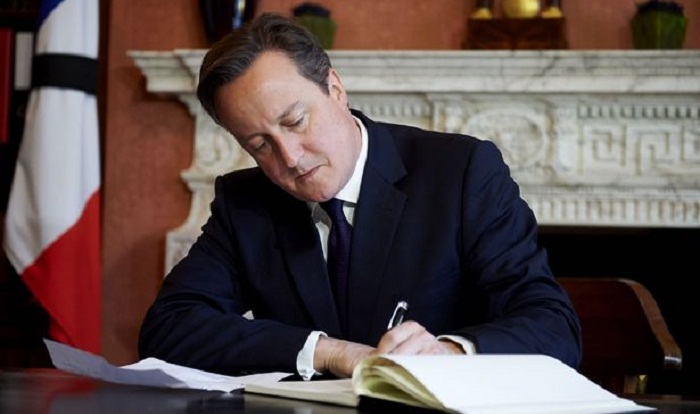

“Everybody will say: ‘We’re sorry, this is a historical disaster but now we have to move on.’ And then they will say ‘OK, David [Cameron], goodbye, because now we have to meet as 27 leaders,’” said one senior diplomat intimately involved in the planning. “That will be rather a decisive moment: will the 27 find the energy, the convergence of views to define a common agenda or whether it will be only the 19?”

French officials are wary of Brexit contagion spreading to other member states and the lift it would provide to anti-EU insurgents like the National Front’s Marine Le Pen. They are determined to send a tough and punitive message to show divorce will be costly for Britain. “Playing down or minimising the consequences would put Europe at risk,” said one senior French official. “The principle of consequences is very important — to protect Europe.”

Another leading European politician central to the Plan B process said: “Making Brexit a success will be the end of the EU. It cannot happen.”

But in Berlin, there is fear that such a harsh message — coupled with grand federalist initiatives — will only aggravate divisions within the EU-27 at a time when bloc unity would be at a premium. “For us it is much better if the price tag is delivered by the private sector [markets],” said one senior German official.

Divisions over further integration were evident this week at a meeting of four of the senior European policymakers: Jean-Claude Juncker, the commission president, Donald Tusk, Council president, Mario Draghi, European Central Bank governor, and Jeroen Dijsselbloem, chair of the eurogroup of finance ministers.

While Mr Juncker and Mr Draghi view Brexit as an impetus for the eurozone to draw closer together, Mr Tusk and Mr Dijsselbloem harbour deep reservations.

“If a negative outcome of the UK referendum should be interpreted as a vote against Europe, it doesn’t make sense in my view to respond immediately by asking for more Europe,” Mr Dijsselbloem told the FT

“The EU has moved ahead in leaps but we haven’t always completed everything. That is our main task: to finish what we have started and show results to our citizens.”

Mr Juncker, meanwhile, said earlier this month: “We have full-time Europeans when it comes to taking and part-time Europeans when it comes to giving ... too many part time Europeans. That is a problem.”

Given such differences, a common agenda on internal and external security — a relatively under-developed area that can also involve non-eurozone member states — is coming to the fore. With the public anxious about terrorism, it could help revive the EU’s battered popularity. Options under consideration include stepping up intelligence co-operation, reinforcing Europe’s external border force, and using the EU treaties to establish joint defence planning and sharing of military equipment.

“If Brexit happens, they will have no choice but to come closer together. Either that, or they stand divided,” said one senior EU diplomat. Steps toward eurozone integration are well mapped out: They range from more risk-sharing and backstops in the event of financial crises to centralising fiscal powers. But they have languished because of a lack of political will.

The secrecy surrounding the talks has sewn confusion over the depth of work and its progress. “We talk but there is no plan. We cannot write anything down,” said one official. Others insist drafting has begun between Paris and Berlin.

At least one contingency blueprint for Brexit does exist: It is in the locked office safe of Mr Juncker’s chief of staff — lying on top of an emergency plan for Grexit that was never used.

More about: