“I am worried that the world’s most important medium is limiting freedom instead of trying to extend it, and that this occasionally happens in an authoritarian way,” he added.

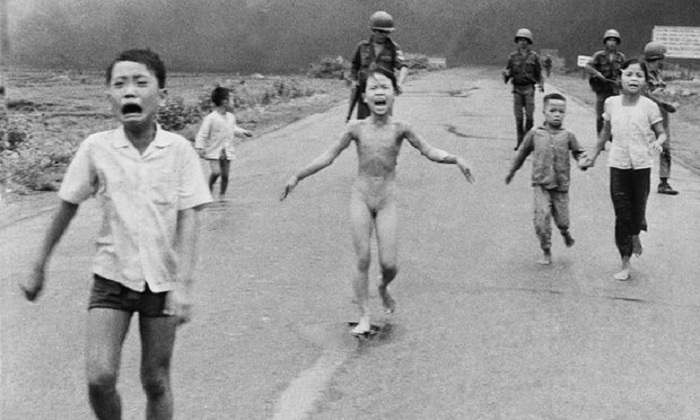

The controversy stems from Facebook’s decision to delete a post by Norwegian writer Tom Egeland that featured The Terror of War, a Pulitzer prize-winning photograph by Nick Ut that showed children – including the naked 9-year-old Kim Phúc – running away from a napalm attack during the Vietnam war. Egeland’s post discussed “seven photographs that changed the history of warfare” – a group to which the “napalm girl” image certainly belongs.

Egeland was subsequently suspended from Facebook. When Aftenposten reported on the suspension – using the same photograph in its article, which was then shared on the publication’s Facebook page – the newspaper received a message from Facebook asking it to “either remove or pixelize” the photograph.

“Any photographs of people displaying fully nude genitalia or buttocks, or fully nude female breast, will be removed,” the notice from Facebook explains.

Before Aftenposten could respond, Hansen writes, Facebook deleted the article and image from the newspaper’s Facebook page.

In his open letter, Hansen points out that Facebook’s decision to delete the photograph reveals a troubling inability to “distinguish between child pornography and famous war photographs”, as well as an unwillingness to “allow[ing] space for good judgement”.

“Even though I am editor-in-chief of Norway’s largest newspaper, I have to realize that you are restricting my room for exercising my editorial responsibility,” he wrote. “I think you are abusing your power, and I find it hard to believe that you have thought it through thoroughly.”

Hansen goes on to argue that rather than fulfill its mission statement to “make the world more open and connected”, such editorial decisions “will simply promote stupidity and fail to bring human beings closer to each other”.

The Aftenposten editorial comes at a time of scrutiny on Facebook for its ever-increasing dominance in the dissemination of news.

News organizations are uncomfortably reliant on Facebook to reach an online audience. According to a 2016 study by Pew Research Center, 44% of US adults get their news on Facebook.

Facebook’s popularity means that its algorithms can exert enormous power over public opinion.

A May 2016 report by Gizmodo that Facebook’s trending bar was deliberately suppressing articles from conservative news sites set off a firestorm that saw Zuckerberg making personal outreach to top conservatives.

Facebook recently fired the team of editors who managed the trending topics section, choosing to replace them with algorithms that quickly demonstrated the difficulty of automating news editorial judgment by promoting a fake news story.

In his open letter, Hansen points out that the types of decision Facebook makes about what kind of content is promoted, tolerated, or banned – whether it makes those decisions algorithmically or not – are functionally editorial.

“The media have a responsibility to consider publication in every single case,” he wrote. “This right and duty, which all editors in the world have, should not be undermined by algorithms encoded in your office in California.”

“Editors cannot live with you, Mark, as a master editor.”

Speaking in Rome last month, Zuckerberg addressed the question of Facebook’s role in the news media and appeared to downplay his editorial responsibilities.

“We are a tech company, not a media company,” he said. “The world needs news companies, but also technology platforms, like what we do, and we take our role in this very seriously.”

Hansen’s suggestions for Facebook to improve its behavior include “geographically differentiated guidelines and rules for publication”, “distinguish[ing] between editors and other Facebook users,” and a “comprehensive review of the way you operate”.

He also called for increased accessibility from the company, writing, “Today, if it is possible at all to get in touch with a Facebook representative, the best one may hope for are brief, formalistic answers, with rigid references to universal rules and guidelines.”

“While we recognize that this photo is iconic, it’s difficult to create a distinction between allowing a photograph of a nude child in one instance and not others,” a spokesman for Facebook said in response to queries from the Guardian.

“We try to find the right balance between enabling people to express themselves while maintaining a safe and respectful experience for our global community. Our solutions won’t always be perfect, but we will continue to try to improve our policies and the ways in which we apply them.”

More about: