Overshadowed by the fighting in Ukraine, another armed conflict in the former Soviet Union — between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the territory of Nagorno-Karabakh — has escalated with deadly ferocity in recent months, killing dozens of soldiers on each side and pushing the countries perilously close to open war.

The month of January was heavily stained by blood, with repeated gun battles and volleys of artillery and rocket fire. Two Armenian soldiers were killed and several wounded in a fierce gunfight on Jan. 23 along the conflict’s northern front. That set off a weekend of violence including grenade and mortar attacks that killed at least three Azerbaijani soldiers.

The most recent clashes prompted an unusually pointed rebuke by international mediators who met on Monday in Krakow, Poland, with the Azerbaijani foreign minister, Elmar Mammadyarov.

“The rise in violence that began last year must stop,” the mediators, from France, Russia and the United States, said in a joint statement, adding, “We called on Azerbaijan to observe its commitments to a peaceful resolution of the conflict. We also called on Armenia to take all measures to reduce tensions.”

Instead, the violence has continued.

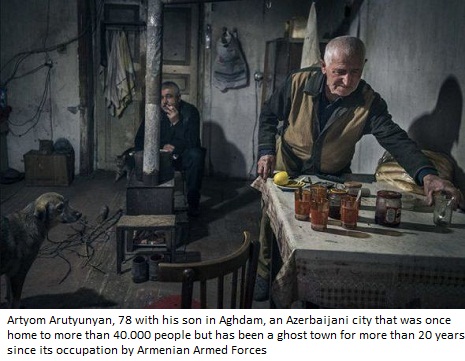

On Thursday, the Azerbaijani Defense Ministry said it had shot down a drone not far from Agdam, an Azerbaijani city that was once home to more than 40,000 people but has been a ghost town for more than 20 years since its occupation by Armenian forces.

Tensions are expected to grow even further this year as Armenia prepares to commemorate in April the 100th anniversary of the genocide against Armenians in Turkey.

While the fighting here often seems to be an isolated dispute over a mountainous patch of land that no one else wants — roughly midway between the Armenian capital, Yerevan, and the Azerbaijani capital, Baku — the conflict poses an ever-present danger by threatening to draw in bigger powers, including Russia, Turkey and Iran.

It also provides a chilling warning of what could be in store for Ukraine, where many fear Russia is intent on turning the eastern regions of Donetsk and Luhansk into a similar permanent war zone.

The recent flare in fighting has been fueled by a quiet arms race, in which both countries — but especially oil-rich Azerbaijan — have built up arsenals of ever more powerful weapons.

Russia is the main supplier to each side, even as it claims a leadership role in international peace negotiations, known as the Minsk Group process, which it chairs with the United States and France.

In recent weeks, President Ilham Aliyev of Azerbaijan has upped the ante, demanding that the Minsk Group leaders take steps to force Armenia to withdraw from Azerbaijani lands — nearly one-fifth of Azerbaijan’s internationally-recognized territory — that it has occupied since a truce was signed in 1994.

“Measures must be taken,” Mr. Aliyev said in a speech to government ministers in January. “The truth is that the continued occupation of our lands is not just the work of Armenia. Armenia is a powerless and poor country. It is in a helpless state. Of course, if it didn’t have major patrons in various capitals, the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict would have been resolved fairly long ago.”

In his speech, Mr. Aliyev warned darkly that Azerbaijan, which has an economy seven times larger than Armenia’s, planned this year to spend more than double Armenia’s entire annual budget of $2.7 billion on strengthening its military.

President Serzh Sargsyan has responded with his own threats. “The hotheads should expect surprises,” Mr. Sargsyan said at a recent military ceremony.

With tensions mounting, visits to each side of the front line, and interviews with senior government and military officials, as well as conversations with dozens of residents, refugees, war veterans, soldiers, local officials, academics, civic activists and even schoolchildren, found the two sides bracing for war, and neither expecting nor prepared for peace.

“We have a saying,” said Col. Abdulla Qurbani, a senior official in the Azerbaijan Defense Ministry, while on a tour of the Azerbaijan side of the line of contact. “When water mixes with earth, this is mud. When blood mixes with earth, this is motherland.”

Across the line in Shushi, a city whose Azerbaijani residents were forced to flee during the war, an Armenian woman, Anaida Gabrielyan, said: “Our land is soaked in blood. Every millimeter is soaked in grief.”

Since fighting began in the late 1980s, it has killed tens of thousands of people and displaced more than a million, many of whom have been living as refugees for more than 20 years.

The increased firepower is not the only reason the conflict has grown more dangerous and more intractable.

The fight is rooted in religious hatreds — real and imagined — between Christian Armenia and predominantly Muslim Azerbaijan.

And a new generation of Armenians and Azerbaijanis, including the soldiers now serving on the front line, cannot remember when their parents and grandparents lived peacefully as neighbors — before Armenians were purged from Azerbaijan and Azerbaijanis were forced from the areas now occupied by Armenia.

In Azerbaijan, there is a city government-in-exile with a single-minded focus on reclaiming the city, called Shusha in Azerbaijani. “Our only goal is to come back,” said Bayram A. Safarov, the head of the administration in exile. “I know every stone there.”

The hardened views in the public mind make it even more difficult to broker an accord, despite Presidents Aliyev and Sargsyan’s having met three times last year.

“The reality is after 20 years of inflammatory rhetoric, both presidents will admit to you that the people of the two countries are just not ready,” said one Western official who has met both men, and who requested anonymity to discuss private conversations on sensitive diplomatic issues.

In Azerbaijan, tens of thousands of refugees live in substandard housing. In some cases, families have lived for years in individual college dormitory rooms, sharing a bathroom on the hall.

The region’s capital, called Stepanakert in Armenian and Xankendi in Azerbaijani, has no functioning airport. And officials there do not have a formal role in the peace process.

Irina Khachaturyan, who sells trinkets from a stall in the central market in Stepanakert, is Armenian but said she dreamed of returning to Baku, the Azerbaijani capital where she lived before the war.

“It was my motherland; I was born there, lived there, studied there,” Ms. Khachaturyan said.

Although she lives among fellow Armenians, she said Stepanakert never became home.

“I never found my place,” she said. “These 25 years, I have been living like on needles.”