Hate speech exploded on Facebook at the start of the Rohingya crisis in Myanmar last year, analysis has revealed, with experts blaming the social network for creating “chaos” in the country.

Evidence of the spike emerged after the platform was accused of playing a key role in the spread of hate speech in Myanmar at a time when 650,000 Rohingya refugees were forced to flee to Bangladesh following persecution.

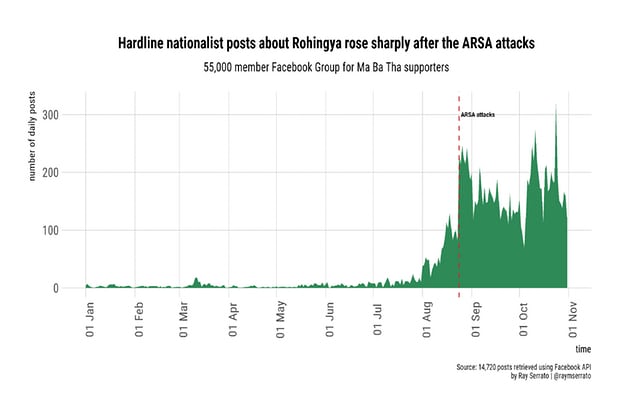

Digital researcher and analyst Raymond Serrato examined about 15,000 Facebook posts from supporters of the hardline nationalist Ma Ba Tha group. The earliest posts dated from June 2016 and spiked on 24 and 25 August 2017, when ARSA Rohingya militants attacked government forces, prompting the security forces to launch the “clearance operation” that sent hundreds of thousands of Rohingya pouring over the border.

A graph of the posts on Facebook in Myanmar after attacks by Rohingya militants that prompted the ‘clearance operation’ Photograph: Facebook/ Ray Serrato

Serrato’s analysis showed that activity within the anti-Rohingya group, which has 55,000 members, exploded with posts registering a 200% increase in interactions.

“Facebook definitely helped certain elements of society to determine the narrative of the conflict in Myanmar,” Serrato told the Guardian. “Although Facebook had been used in the past to spread hate speech and misinformation, it took on greater potency after the attacks.”

The revelations come to light as Facebook is struggling to respond to criticism over the leaking of users’ private data and concern about the spread of fake newsand hate speech on the platform.

Alan Davis, an analyst from the Institute for War and Peace Reporting who led a two-year study of hate speech in Myanmar, said that in the months before August he noticed posts on Facebook becoming “more organised and odious, and more militarised”.

His research team encountered fabricated stories stating that “mosques in Yangon are stockpiling weapons in an attempt to blow up various Buddhist pagodas and Shwedagon pagoda”, the most sacred Buddhist site in Yangon in a smear campaign against Muslims. These pages also featured posts calling Rohingya the derogatory term “kalars” and “Bengali terrorists”. Signs denoting “Muslim-free” areas were shared more than 11,000 times.

When the monitors working with Davis called officials about the signs, they were told the officials knew nothing about them. When he tried to fund a team of local journalists to investigate and report on them, the journalists all declined for reasons of safety.

Davis said this was the defining moment. “People just thought ‘oh well, we can just keep on doing what we do.’”

Among Myanmar’s 53 million residents, less than 1% had internet access in 2014. But by 2016, the country appeared to have more Facebook users than any other south Asian country. Today, more than 14 million of its citizens use Facebook. A 2016 report by GSMA, the global body representing mobile operators, found that in Myanmar many people considered Facebook the only internet entry point for information, and that many regarded postings as news.

One cyber security analyst in Yangon, who asked to remain anonymous for fear of online attacks, said: “Facebook is arguably the only source of information online for the majority in Myanmar.”

In early March, UN Myanmar investigator Yanghee Lee warned that “Facebook has become a beast.” “It was used to convey public messages but we know that the ultra-nationalist Buddhists have their own Facebooks and are really inciting a lot of violence and a lot of hatred against the Rohingya or other ethnic minorities,” she said.

Myanmar has agreed to a visit by the UN security council after months of resistance, but it remains unclear whether ambassadors will be allowed to go to Rakhine state, the body’s president said Monday.

A Facebook spokeswoman said the company was ramping up efforts to remove hate content and people who repeatedly violate the company’s hate-speech policies. “We take this incredibly seriously and have worked with experts in Myanmar for several years to develop safety resources and counter-speech campaigns,” she said.

“We now have around 14,000 people working across community ops, online ops and our integrity efforts globally – almost double where we were a year ago – and will have more than 20,000 by the end of this year.”

On Monday, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg told Vox that the spread of hate speech on the platform in Myanmar was “a real issue”.

Serrato called on Facebook to be more open with its data. “Right now, we have no way of knowing which people like or share certain posts so we cannot track how disinformation or hate speech spreads on the platform.”

But Davis said the damage was done. “I think things are so far gone in Myanmar right now ... I really don’t know how Zuckerberg and co sleep at night. If they had any kind of conscience they would be pouring a good percentage of their fortunes into reversing the chaos they have created.”

Facebook has been accused of fomenting violence elsewhere in the region. In March the Sri Lankan district of Kandy was the site of mass riots and arson by Buddhist nationalist fanatics.

The Sri Lankan minister for telecommunication, Harin Fernando, told the Guardian the government ordered Facebook and other social media services to be shut down at the height of the violence. “This whole country could have been burning in hours,” Fernando told the Guardian.

An analysis of 63,842 Facebook posts by Yudhanjaya Wijeratne, an author and data researcher, concluded the social media ban took fewer than half the country’s Facebook users offline, many likely turning to a VPN to access the service.

The Guardian