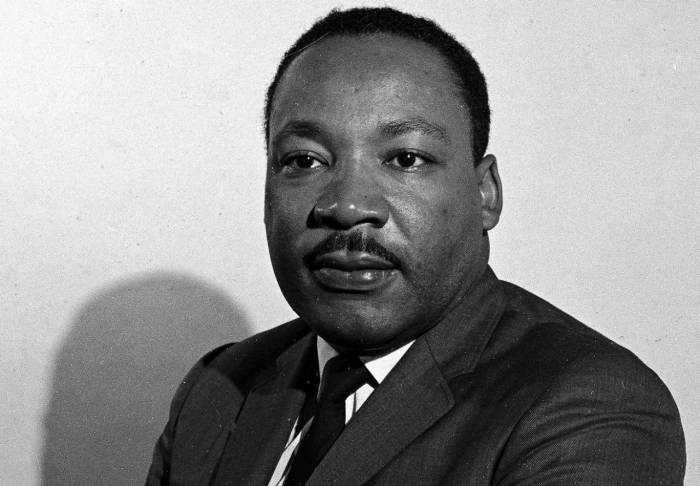

While the man who would assassinate him the next day was holed up in the New Rebel motel, hundreds of people were filtering into Mason Temple, in Memphis, Tennessee, to hear Martin Luther King Jr, speak. Outside, a thunderstorm was raging. The people clustered in the front of the church, shedding their rain-spattered jackets as they took their seats.

Then they waited.

King was an hour and a half late. Pausing a moment as he stepped to the rostrum, he peered over a welter of microphones. As TV cameramen flooded him with light, his face took on a luminous sheen. But something seemed amiss.

After he greeted the audience, he lauded them for braving the storm, coming to the rally, showing that they had the backbone to carry on with the Memphis sanitation workers’ strike.

In the words to follow King had nothing more to say about the storm. Yet you could say that the storm still had something to say to him. Time and again, wind gusts punched open two large window fans near the ceiling of the auditorium. The shutters clacked shut each time, startling King.

“Every time there was a bang,” Billy Kyles recalled later, “he would flinch.”

King looked “harried and tired and worn and rushed”, observed one minister. He had a sore throat and was sleep-deprived. By the end of the speech that he would deliver that night, everyone in Mason Temple would know another reason why he seemed out of sorts.

There had been no time to prepare, even if he had intended to do so.

King often spoke without notes, even when the stakes were extremely high. He was doing it again on this night. He had an astonishing knack for speaking off the cuff. He seemingly had a photographic memory.

In his first big moment as a civil rights leader, during the kickoff rally to commence the Montgomery bus boycott in 1955, he had 20 minutes to compose his remarks. He had delivered a riveting speech that had his audience clapping and howling their support. The “I have a dream” finale of his speech at the March on Washington in 1963 catapulted him to legendary heights. That stunning riff was famously a spur-of-the-moment departure from the prepared text.

The first theme of his remarks at Mason Temple that Wednesday night seemed far removed from Memphis. Imagine, he said, still speaking quietly, that the “Almighty” was transferring him back in time. King’s first stop, he said, would be Egypt in biblical times. He would visit classical Greece, the Roman Empire, the Renaissance, the Christian Reformation under his namesake Martin Luther, and Lincoln’s signing of the Emancipation Proclamation.

King said he would not stop his trip through history there. No, he would ask the Almighty to allow him to live in current-day America.

The specifics of the trip through time, of course, were not the point of King’s speech. They were a rhetorical device to lend emphasis and gravity to his words. It was the kind of flair that King employed to infuse his speeches and sermons with dramatic power. In the Memphis speech he was mixing the simplicity of a children’s story, a bird’s-eye view of history, with references to lofty historical figures.

As he imagined the stop in ancient Greece, he spoke of his expectation that he would bump into Pluto, Aristotle, Socrates, Euripides and Aristophanes. If few of his listeners would have recognized all those names, that did not matter. King was burnishing his speech with a dash of intellectual gloss. It was not just Martin Luther King speaking. It was Dr King, the theologian with a PhD from Boston University. It was a learned man who could rattle off the names of ancient philosophers and dramatists to poetic effect.

Advertisement

His voice built in intensity and rose in volume as he went on. That voice, a rich baritone, seemed to emerge from deep within him, as though rumbling from an oak barrel. His voice was almost musical in its harmonic rise and fall. It was at once lucid and richly ornate.

On another occasion the timbre of that voice had bowled over the newspaper columnist Mary McGrory. Writing in the Washington Evening Star on 16 December 1966, she noted how “baroque phrases” slid off his tongue in “mellifluous, mesmerizing tones”.

King’s voice could, depending on the race or sophistication of his audience, exhibit the clipped diction of a lofty academic or the earthy vernacular of African American speech. For example, on one occasion, in 1965, when he was speaking in the vernacular, he proclaimed from the steps of the Alabama statehouse at the conclusion of a triumphant march from Selma to Montgomery: “We ain’t goin’ let nobody turn us around.”

In Memphis, however, as he moved to a major theme of his speech at Mason Temple, King turned darkly pessimistic.

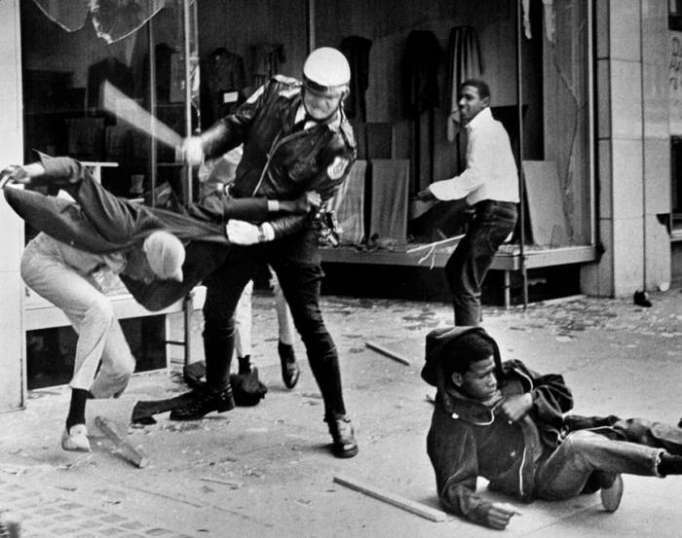

A police officer uses his nightstick on a youth reportedly involved in the looting that followed the breakup of a march led by Martin Luther King on 28 March 1968 in Memphis, Tennessee. Photograph: Jack Thornell/Associated Press

The choice for humankind was no longer between violence and nonviolence, King said. Tapping his fingers on the rostrum, he said the choice was between nonviolence and “nonexistence”. Unless the government moved swiftly to alleviate the poverty of African Americans, he went on, the nation was doomed.

It was not a momentary lapse into overstatement. King had been saying much the same thing for months. He was warning of catastrophe – nothing less. It was why he saw poverty as an issue of overriding urgency.

Then King shifted to another message, a plea for unity. He urged the strikers to stick together, invoking a passage from the Old Testament. Just as the slaves of ancient Egypt united against the Pharaoh to escape their bondage, so the strikers had to stay together, united.

King had a keen sense of what messages and symbols would resonate with which audience. Relying on biblical tropes was very much in tune with the makeup of the crowd at Mason Temple. Ingrained in the marrow of most everyone in that auditorium was a biblical heritage and Christian belief.

Religious motifs came naturally to him. Even when King was a small boy, his father, the Reverend Martin Luther King Sr, had him memorizing scripture and reciting it at the dinner table. His mother, a church organist, instilled a religious spirit through the power of song.

Every Sunday King had sat in a wooden pew of his father’s church. Before his eyes were the biblically themed stained glass windows above the pulpit. Into his ears poured Gospel-laden sermons and the voices of the white-robed choir, all radiating the Christian faith and the African American Baptist tradition.

From a young age he had displayed a knack for public speaking. He was only 15, in his last year of high school (he skipped two grades in high school), when he won a statewide oratorical contest for African American students. When he was 18, his father invited him to deliver a trial Sunday-afternoon sermon at Ebenezer.

Though he had no formal training in the ministry, he obliged. King biographer Taylor Branch described what happened: the novice preacher “seemed to project his entire being in the expression of his sentiments”, and the worshippers “rose up in celebration”.

As a graduate student in theology King honed and refined his speaking style. He mastered the charismatic techniques and sermonizing of African American Baptist preachers. He scrutinized and memorized their mannerisms until he could do dead-on imitations. He had a repertoire of them, and years later he would amuse his aides with exaggerated renditions of one preacher’s style or another.

He was alert to the possibilities of metaphor and imagery and systematic in building a stock of rhetorical material. In a brown pocket-sized spiral notebook he jotted down witticisms that caught his eye. “Nothing so educates as a shake” was one scribbling. Another was from Jean-Jacques Rousseau: “Above the logic is the feeling of the heart.”

-1522839510.jpg)

Martin Luther King stands with other civil rights leaders on the balcony of the Lorraine motel in Memphis, Tennessee, on 3 April 1968, a day before he was assassinated at approximately the same place. Photograph: Charles Kelly/AP

Flashes of King’s mastery with words were on display at Mason Temple that Wednesday night.

As he often did in his speeches, he elevated a local issue into a sweeping, transcendent national cause. He implored his listeners to support the garbage workers of Memphis. By doing so, he said, they would not just shape their city’s future; they would also transform the nation with their example.

Then his speech took a highly personal turn. He told of being stabbed in 1958 by a crazed African American woman while he was signing books in Harlem. The tip of the blade lodged in his chest a fraction of an inch from his aorta.

Surgery removed the knife and repaired the wound. He later learned that he had been extremely lucky. If he had so much as sneezed while the knife impinged on the artery, he would have died. He told of receiving a letter from an 11-year-old girl. King quoted from the letter in which the girl said she was glad that he had not sneezed.

The story of the stabbing and the girl’s letter served as a rhetorical lead-in for a recap of his career. “If I had sneezed,” he sang out over and over in a melodic refrain, each time citing a key event in the civil rights movement that he would have missed had he died from the stabbing in Harlem.

If he had sneezed, he said, he would have missed the sit-in protests to desegregate lunch counters. If he had sneezed, he would have missed the Freedom Rides to end Jim Crow on interstate buses, the Birmingham campaign, the enactment of the federal civil rights bills, the chance to deliver the I Have a Dream speech in Washington, the showdown in Selma over voting rights, and the outpouring of community support in Memphis for the strike that had brought him there.

Reciting the story about his near death seemed to transport him into a profound gloom about mortality – his mortality. Still fresh on his mind was the death threat that forced the delay of his flight from Atlanta that morning, and he could not let it go now.

He told his listeners how the airline had taken the threat seriously because he was on board, had guarded the plane during the night and checked all the passengers’ bags for explosives. Upon his arrival in Memphis, King said, he had heard yet more talk about death threats against him.

He continued in a melancholy, self-reflective mood, saying he was facing some difficult days ahead. But he said he was prepared for anything, no matter what might lay ahead, because he had “been to the mountaintop”.

His words reflected a soul searching as he contemplated the specter of death. He had talked many times before about his fear of dying a violent death. But it was unusual for King to dwell openly on the depth of his despair as he pondered his fear of death. His manner typically was lighthearted, self-assured, and unflappable.

This night in Memphis, however, he seemed near panic, anxious that he might be the target of an assassin’s bullet at any moment.

Martin Luther King lying in state in Memphis, Tennessee. Photograph: Keystone/Getty Images

For many years King had dealt openly with that fear. During his earliest civil rights leadership, in Montgomery, his front porch had been bombed. He proclaimed defiantly at a rally soon afterward: “Tell Montgomery that they can keep bombing, and I’m going to stand up to them. If I had to die tomorrow morning, I would die happy because I’ve been to the Mountaintop, and I’ve seen the Promised Land, and it’s going to be here in Montgomery.”

Two months before speaking at Mason Temple, in a Sunday sermon at Ebenezer, he dwelled on the prospect of his early death, effectively preaching his own eulogy. No need to catalog all the honors bestowed on him, he said. Rather, he said, “I’d like somebody to mention that day that Martin Luther King Jr, tried to give his life serving others … [that he] was a drum major for justice.”

Not long after, on 12 March, he sent synthetic red carnations to his wife. Until then all the flowers he had ever given her had been real. In justifying his choice of flowers, he told Coretta: “I wanted to give you something that you could always keep.”

In late March, as he girded himself for the return to Memphis, he confided to his parents that they ought to brace for his death at any time.

Now, as he concluded his speech at Mason Temple, he seemed to be coming to terms with death to an extent that he had not voiced publicly before.

King’s voice rose to its highest pitch yet. His eyes blinked rapidly, as he turned his head from side to side. He acknowledged that he wanted to live a long life but that he was resigned to whatever might happen. He said that God had allowed him to reach the mountaintop and see the Promised Land.

Then he vowed resolutely, nobly: “I may not get there with you. But I want you to know, tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land!”

He ended with an utterance of religious fervor, saying that he was not worried, that he did not fear anybody, exclaiming in a final flourish, “Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.”

That borrowing from the Battle Hymn of the Republic was a staple of his oratory. The words, penned by Julia Ward Howe in 1861, venerate a fierce fight to the death in the name of freedom for American slaves. It is a call to abolitionists to follow Jesus in sacrificing themselves for a righteous cause.

If King had completed the stanza, he would have added: “The truth is marching on.” But he did not. His wife, Coretta, reading his words spoken at Mason Temple, would think that he had become so overcome by emotion that he could not finish the stanza.

Coming to terms with the prospect of his death and his own sacrifice, King was approaching grandiosity. He was comparing himself to Jesus and Moses – to the Jesus heralded in the Battle Hymn and to the Old Testament’s celebration of the Moses who had led his people toward the Promised Land.

Other speeches had drawn the parallel between the civil rights movement and the Exodus story. Now he was adding a new element. As Moses was to the Israelites’ struggle for freedom, he seemed to be saying, he was to African Americans’ struggle for freedom. As he stared at the face of death, he was portraying himself as the Moses of his time.

Coretta Scott King leads a march of some 10,000 mourners in Memphis, four days after King’s death. Photograph: Bettmann/Bettmann Archive

King had talked for 43 minutes. Spent by the exertion, tears welling in his eyes, he turned and staggered toward his chair on the podium. Wobbly, he seemed to lose his footing.

Ralph Abernathy caught him and steered him into the chair. “It was as though somebody had taken a beach ball and pulled the plug out, as if all his energy had been sucked out,” the lawyer Mike Cody recalled.

As King collapsed into his chair, the crowd rose up from theirs, roaring and clapping. Historian Joan Beifuss later described the crowd as “caught between tears and applause”.

Even among the ministers in the auditorium who knew King’s oratory well, the emotional charge of his words provoked shivers. “I’d never heard the intensity or the passion or the drama in his voice, in how he was delivering it, and he kept getting stronger and stronger,” Billy Kyles later said.

He would add that King seemed to be preparing for his death by purging publicly “the fear. He had to get rid of it. He had to let all that go.”

In his memoir, Abernathy wrote: “I had heard him hit high notes before, but never any higher.” Jesse Jackson would call his wife to tell her, “Martin had given the most brilliant speech of his life … he was lifted up and had some mysterious aura around him.”

Years later, Jackson noted: “What I thought was so different about that sermon, I saw men crying,” not something that happens usually in church. By the end, Kyles would say, “We were on our feet clapping and hollering.”

As often happened at the end of a compelling speech by King, the crowd surged toward him. Rather than allow a crowd to crush him, he usually exited quickly. “But that night he just didn’t want to leave,” Beifuss quoted a local minister as saying.

“He just wanted to stay there and meet people and shake their hands and talk to them.” It was not an ordinary night.

This is an adapted excerpt from Redemption: Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Last 31 Hours by Joseph Rosenbloom (Beacon Press, 2018). Reprinted with Permission from Beacon Press.

The original article was published in the Guardian.

More about: