Organisations work “very hard” to make pay opaque, she says. “They know they can’t always justify differences. It’s in [their] interest as an employer not to be open about these things.”

Such secrecy puts workers at a huge disadvantage in negotiating salary, says Alison Green, the US management consultant behind the site Ask A Manager, who has compiled an anonymous database on pay. “It also makes it far harder to uncover pay disparities by gender or race.”

Professor Simms has in the past usefully shared salary levels with peers, although admits to having needed to fortify herself in the pub beforehand to pluck up enough courage. “Almost any conversation that gives a number to your worth comes with [baggage]; it can be emotional, you think your peers will judge you.”

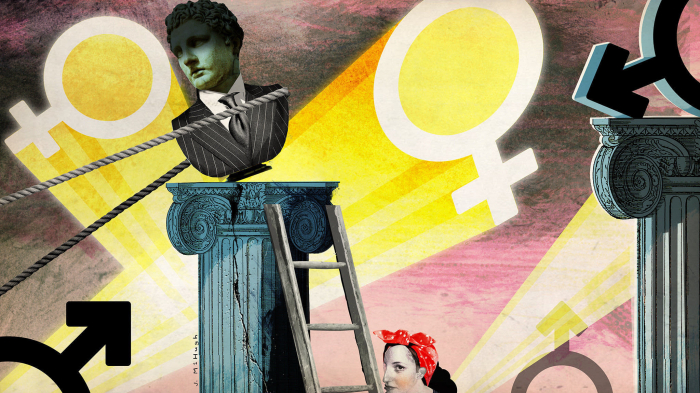

Pay has long been considered a taboo subject in many parts of the world. As Kim Scott, previously at Google and Apple, and author of Radical Candor, puts it: “We behave about money the way the Victorians behaved about sex.” Technology and legislation are shifting attitudes to pay secrecy. At its most extreme, some companies have embraced radical transparency — making their staff’s salaries accessible to each other. Could this be the future?

Social media has made the private public, and websites such as Glassdoor and Salary Expert help workers find information about pay. At the same time, legislation has brought pay under public scrutiny. In the US and UK, listed companies are required to publish the pay ratio between chief executives and workers’ averages. Gender pay gap reporting has been introduced in the UK and France. A new law in Germany allows women to ask for the median salary of a group of at least six men doing similar work, and vice versa.

Publishing pay information can trigger dissatisfaction and dissent — notably at the BBC, the UK broadcaster.

In 2017, the BBC revealed that two-thirds of its highest paid stars were men. The following year, Carrie Gracie resigned from her post as China editor, writing in an open letter that the broadcaster was “breaking equality law and resisting pressure for a fair and transparent pay structure”. In response to complaints, in March the Equality and Human Rights Commission launched an investigation into unequal pay at the broadcaster. The BBC acknowledged that there had been historic equal pay cases but subsequent independent reviews “did not find systemic issues of pay discrimination” and is making “improvements to pay structures”.

One BBC employee says that the pay controversy has encouraged some men to share their salary levels with female staff, so they can discover if they are being underpaid. “It can be immensely helpful. The genie is out of the bottle. We believe that transparency is right in court proceedings, in MPs’ expenses. We need to be more prepared to be open with each other about what we earn.”

Sam Smethers, chief executive of the Fawcett Society, a gender equality charity, says that asking a peer for their salary level can be an “important” step in revealing pay discrimination. This is no easy task. Research by the Fawcett Society last year found that 53 per cent of female workers and 47 of male workers would be uncomfortable disclosing their pay to a peer. However, when they believed there was discrimination, 62 per cent of women and 57 per cent of men would share the data.

Transparency can keep employers in check. A study published in 2015 concluded optimistically that organisational transparency over pay “can also help reduce gender and racial inequality in the workplace”.

In some cases, being open may purge paranoia among workers who are suspicious about unequal pay. Women discover they are paid fairly, while men might find out they are underpaid.

Learning that a peer earns more than you may be demoralising and trigger a hunt for a new job, but the converse is true of your manager. Discovering the boss has a higher salary can motivate an employee to strive harder. This is according to researchers at Harvard Business School and UCLA’s Anderson School of Management who looked at 2,000 employees at a bank.

While quitting to seek better pay may be rational, some argue that most workers are delusional about their ability and value. Todd Zenger, author of Beyond Competitive Advantage, argues in an article that: “Widely publicising pay simply reminds the vast majority of employees, nearly all of whom possess exaggerated self-perceptions of their performance, that their current pay is well below where they think it should be.”

Even advocates of radical pay transparency, do not see it as a panacea. Paulina Sygulska Tenner, co-founder of GrantTree, which helps tech companies find public funding, has shared salaries internally from the outset. It has had “its challenges”, she says.

Pay transparency, she says, has to be part of an open culture. In her company, which launched in 2010, employees can also access corporate information including the accounts and departmental budgets. “My co-partner and I wanted to create a place where we wanted to work. We give [employees] the message that we trust them,” says Ms Tenner.

Two years ago, they introduced a new pay scheme whereby employees research and set their own salaries. Over several months they gather information about their pay, based on skill level, performance and market value. They then receive feedback on their proposal before making a final decision.

Pay transparency, she thinks, stops water-cooler gossip about salaries.

Some people have taken a pay cut as they have changed roles. One employee moved from being a senior client manager to marketing and said it was reasonable to reduce her salary, though it was not lowered to the level of a junior marketer, on the basis that she was saving recruitment costs and the time spent bringing a new recruit up to speed on the company.

To go transparent on pay, Ms Tenner says, employees need to be financially literate. “If people can’t understand that, we can’t expect them to make good decisions.”

This conclusion is echoed by Hans Christian Holte, director of the Norwegian tax administration. Norway is widely held up as exemplary on transparency. It makes its citizens’ tax returns public and accessible. Financial literacy, he says, is “a big issue”.

If employers are considering transparency, they need to be clear about job roles and justifications for pay differences and rewards. Charles Cotton, senior adviser for performance and reward to the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development, says: “It forces an organisation to think about what it’s rewarding and why.”

These guidelines will need to be updated periodically — skills that were once highly sought after fall out of favour; jobs change.

One pay expert says that asking a large established company to open the payroll suddenly is disorientating, comparing it to a spouse proposing that a monogamous marriage should become open. Ms Tenner suggests large companies considering transparency should start small — perhaps with a single department.

Ruben Kostucki is chief operating officer at Makers Academy, a software developers’ training company that has 50 employees and has had pay transparency since its foundation in 2013. He says it is a lot easier as a small and new company that can “take risks”.

He believes pay transparency makes employees clear about their goals. While transparency is “probably fairer”, he says, “I don’t want anyone to think it’s a magic bullet. We are not trying to make everyone happy but be open and honest with employees.”

“We don’t put everyone’s salaries on a whiteboard every day, it just means they are accessible. Most people don’t care. We’ve got better things to do.”

Read the original article on Financial Times.

More about: transparency