Demand and supply since September

Wonkblog writes that there’s one short-term reason and three longer-term reasons for this slump. The meeting was the most important in years, because it came amid a pre-existing slump in prices. Everybody wanted to know if OPEC would take any action to halt the decline. It didn’t — presumably because its members decided it was wiser to weather the current storm — and crude oil prices immediately tanked. The long-term reasons include booming U.S. and world oil production, little demand in Europe and Japan, and improving automobile fuel efficiency standards.

Brad Plumer writes that up until very recently that US oil boom — along with increases in Canada and Russia — had a fairly minimal effect on global prices. That’s because, at the exact same time, geopolitical conflicts were flaring up in key oil regions. There was a civil war in Libya. Iraq was a mess. The US and Europe slapped oil sanctions on Iran and pinched that country’s exports. Those conflicts took more than 3 million barrels per day off the market. Things changed again around September 2014. Many of those disruptions started easing. Libya’s oil industry began pumping out lots of crude again. And even more significantly, oil demand in Asia and Europe has been weakening — particularly in places like China, Japan, and Germany.

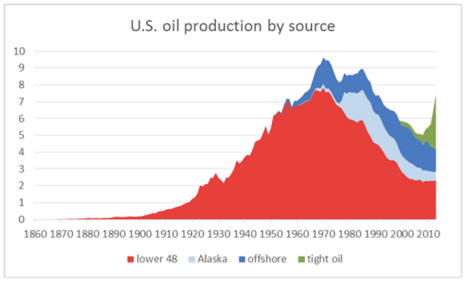

James Hamilton writes that the current surplus of oil was brought about primarily by the success of unconventional oil production in North America, most new investments in which are not sustainable at current prices. Without that production, the price of oil could not remain at current levels. It’s just a matter of how long it takes for the high-cost North American producers to cut back in response to current incentives. And when they do, the price has to go back up.

Brad Plumer writes that this marks a big shift in global oil politics. Essentially, OPEC is now engaged in a price war with oil producers in the United States. The cartel will let prices keep falling in the hopes that many of the newest drilling projects in the US will prove unprofitable and shut down. It’s very cheap to pump oil out of places like Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. But it’s more expensive to extract oil from shale formations in places like Texas and North Dakota. So as the price of oil keeps falling, some US producers may become unprofitable and go out of business. The result? Oil prices will stabilize and OPEC maintains its market share. The catch is that no one quite knows how low prices need to go to curb the US shale boom. According to the International Energy Agency, about 4 percent of US shale projects need a price higher than $80 per barrel to stay afloat. But many projects in North Dakota’s Bakken formation are profitable so long as prices are above $42 per barrel. We’re about to find out how this all shakes out — and which numbers are correct. Tyler Cowen writes that because of fixed costs and option value, a currently unprofitable project can remain up and running for a long time to come.

Oil prices and inflation expectations

VCpost writes that one of the most obvious effects of falling oil prices is that it brings down inflation and exerts a downward pressure on inflation expectations. Under normal economic conditions, falling inflation could be seen as positive under, but in the present circumstances with major economies struggling to meet the inflation target of around 2 percent, plunging oil prices is not good news.

Tony Yates writes that the argument for loosening is that on account of oil being a major input, it will raise potential output relative to actual output. Which in models like those central banks uses is deflationary. Also, if inflation expectations are extrapolative, a temporary oil price fall would lower inflation expectations, transmitting into core inflation. (Inflation itself being lower on account of the fall in expected inflation). Neil Irwin writes that to the degree those one-time shifts change peoples’ expectations about future inflation, and lead people to doubt the credibility of the central banks’ promises to keep inflation at 2 percent, it is a problem. That’s particularly true when inflation expectations are already below where the likes of Mario Draghi, Janet Yellen and Haruhiko Kuroda would prefer.

Michael Mackenzie writes that while the Fed has played down the recent drop in break-even measures, the slide in oil prices has not escaped the attention of consumers. The University of Michigan’s consumer sentiment survey last week showed a drop in long-term US inflation expectations from 2.8 per cent to 2.6 per cent, the lowest level since 2009. Olivier Coibon and Yuriy Gorodnichenkopoint that household expectations might be more important than professional forecasts for the dynamic of inflation. More than half of the historical difference in inflation forecasts between households and professionals can be accounted by the level of oil prices. Because gasoline prices are among the most visible prices to consumers, households pay particular attention to them when formulating their expectations for other prices. Coibon and Gorodnichenko present evidence that firms’ inflation expectations are, in fact, better proxied by household than by professional forecasts.

Other channels

Gavyn Davies writes that the disinflationary effects are uncontroversial. But the boost to growth is more debatable, since lower oil prices involve a redistribution of income from oil producers to oil consumers. Why should this reallocation of resources lead to a rise in real gross domestic product? It is because of time lags. Oil consumers, which are mainly households, have seen their real incomes rise, perhaps permanently, and they are assumed to allocate part of this gain quite quickly to increased real expenditure on other goods and services. Oil producers, on the other hand, are mainly rich governments and corporates, and they may take much longer to reduce their expenditure in line with their lower real incomes. That, anyway, is what economic models tend to assume when oil prices decline for supply-related reasons.

James Hamilton writes that lower gasoline prices likely also contributed to the recent rise in consumer sentiment. Historically a 20% drop in energy prices would predict a 15-point rise in consumer sentiment. That relation weakened considerably as consumers got accustomed to the up-and-down yo-yo of prices in recent years. Nonetheless, consumer sentiment is now at the highest level it’s been since the Great Recession.

Published in collaboration with Bruegel

Author: Jérémie Cohen-Setton is a PhD candidate in Economics at U.C. Berkeley and a summer associate intern at Goldman Sachs Global Economic Research.