The study, published Monday in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, found that scores on cognitive tests -- including verbal memory and orientation of time -- dropped faster after patients received such a diagnosis than they did leading up to it.

"This study adds to the increasing body of literature that showcases how the heart and brain work together," said Dr. Neelum T. Aggarwal, director of research for the Rush Heart Center for Women and a cognitive neurologist at its Cardiology Cognitive Clinic. She was not involved in the study.

"We are now seeing more issues related to cognitive function from heart disease as more people are living longer, and also undergoing more heart procedures, and placed on medications," Aggarwal wrote in an email.

The authors of the study say previous research on the issue has been a mixed bag, often focused on the role of conditions like strokes and sometimes showing a more rapid cognitive decline thereafter. But the new study found a longer-term impact on the brain, following up with stroke-free adults for a median of 12 years and looking at a subset who had been diagnosed with a heart attack or angina, a kind of chest pain resulting from decreased flow of blood to the heart.

Heart attack patients "had a significantly faster memory decline than those with an incident angina," the authors noted.

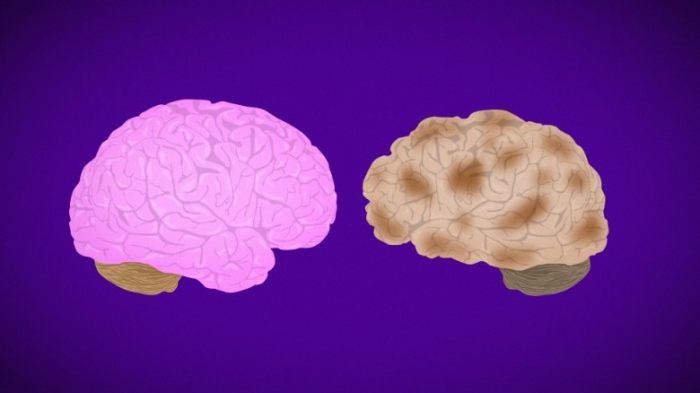

Cardiovascular disease is thought to affect the brain in multiple ways, experts say. It could impact small blood vessels, disrupting the flow of oxygen to parts of the brain. And the link between the two could stem from common risk factors that start earlier in life, such as obesity, diabetes and high blood pressure. The new findings suggest that there could be a gradual process at play affecting blood flow and the brain, but how it works is still unclear, according to a commentary published alongside the new study by doctors at the University of Turku in Finland.

Whether there could be other external factors is also unclear. For example, the authors note that they couldn't exclude the potential impact of medications and other treatments that doctors might prescribe to newly diagnosed heart disease patients.

"Teasing out what contributes the most to cognitive decline may be difficult," Aggarwal said, "as persons with heart disease have multiple medical conditions operating at the same time.

"Medications are a huge factor," she added -- including whether they are taken as prescribed.

Despite the changes in cognitive scores appearing "relatively small," according to the commentary, the study authors say that "even miniscule differences in cognitive function can result in a substantially increased risk of dementia over several years." And because no cure exists, they say, finding ways to detect, prevent and intervene early could be our best bet to address the problem, for now.

Aggarwal said there are valuable messages in the study, drawing on her own work at the Cardiology Cognitive Clinic, where her team helps patients address chronic conditions that could take their toll on brain health.

"First step is to encourage patients to tell their physicians about their memory concerns," Aggarwal said. "Often patients don't mention this."

She also encouraged doctors and patients to go over medications and be sure they're taken as prescribed, to address other possible causes like mood and sleep, and to talk about lifestyle changes that can have a positive effect on overall health.

"What is good for your heart is good for your head," Aggarwal said.

More about: brain heart-disease