It looks like a thick, dark stew bubbling on the stovetop. Or a bulbous living being trying to escape from the black sludge on the ground. It is, however, none of those, but the natural forces acting up at the mud volcanoes in Gobustan (also called Qobustan), close to Azerbaijan’s capital Baku. Azerbaijan is rich in natural oil resources, a place where volcanic activity below the earth causes strange phenomena — like the fire burning non-stop through wind and rain on the mountain at Yanar Dag for probably hundreds of years now, and the wide craters spewing a thick magma-like substance at the mud volcanoes of Gobustan.

There are an estimated 700 mud volcanoes in the world, and nearly half of them are found in the post-apocalyptic, lunar landscape of Gobustan National Park along the Caspian Sea. Mud volcanoes are formed at places where the subterranean methane gas forces its way up through a weak spot in the earth. So, does volcano mean these eruptions are fiery hot? It turns out, no. I dip my hand into the frothing mud with great trepidation, urged on by my guide; will I get sucked deep towards the core of the earth if I slip and fall into the crater. The mud is cold, close to freezing, drying up instantly when I take my hand out.

Around me, a dramatic scene is unfolding at the edge of the crater, featuring a group of young British tourists. One of the men has taken off his shirt and is being incited by his friends to jump in. He flexes his muscles in a show of false bravado and steps gingerly into the mud. I look on breathlessly, while others are busy digitally documenting his adventure for posterity. He is standing shoulder-deep in the mud, a high wattage smile of achievement on his face. Apart from being good for the skin, the volcanic mud is believed to have curative properties for ailments of the nervous system, painful joints and so on. However, this is nothing but high jinks, and he soon emerges from the mud to the sound of whistles and whoops.

Climbing down from the mound, I walk back on the path of dried earth that is cracked and gaping, to where my USSR-era chariot is waiting to take me back to civilisation. An hour earlier, I had gotten off the big tourist bus that had ferried me from Baku, and been transferred into a Premier Padmini-lookalike car that seemed to run on pure willpower. My driver had raced through a long stretch of unpaved and unmarked territory — calling it a road would be a stretch — before pulling up close to the volcanoes.

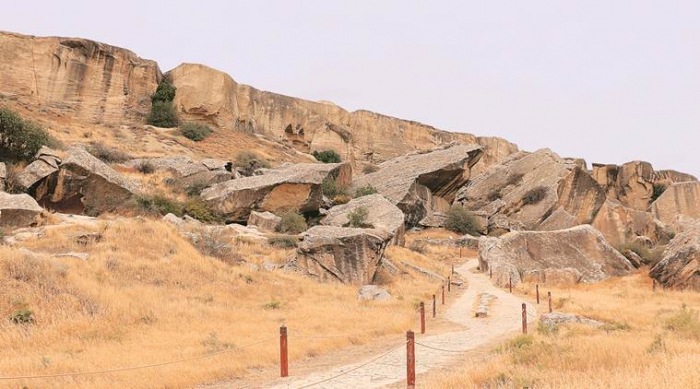

By the time I am back on the bus, I am covered in a thick patina of dust and clumps of black mud. We then drive a few minutes to where the petroglyphs are. Derived from the old Greek “petro” for stone and “glyphein” meaning to carve, petroglyphs are simple etchings on rocks. Gobustan National Park has one of the largest such collections of petroglyphs anywhere in the world, with some of them dating back over 40,000 years to the last Ice Age. Known as the Gobustan Rock Art Cultural Landscape, this outdoor museum has over 6,000 such pieces of rock art on boulders and cave walls.

These petroglyphs were discovered quite by accident in the 1930s when quarrying work was being carried out in the region. It is now a protected area, with the Unesco adding it to the World Heritage site list in 2007. On a short tour through the rocky landscape, my guide points out the petroglyphs, depicting various scenes from daily life — stick figures dancing, hunting and cooking, as well as the animals they herded and hunted, including deer, goats, bulls and horses. Ancient tools and weapons were also found on the site, indicating these caves were once inhabited by the artists. The most fascinating of the petroglyphs is a set of reed boats. The art is not sophisticated, but the boats resemble the ones etched in similar rock art found in Scandinavia. There are new petroglyphs and artefacts being discovered here all the time. After all, these ancient rocks do not give up their secrets so easily.

Read the original article on indianexpress.com.

More about: Azerbaijan