The 23 Meiji period (1868-1912) sites include coalmines and shipyards that Japan says contributed to its transformation from feudalism into a successful modern economy.

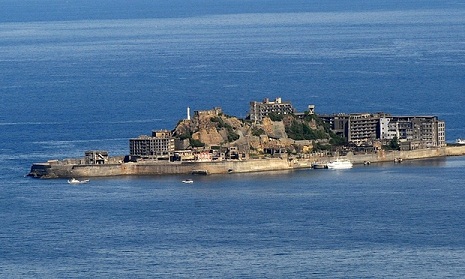

South Korea, however, had opposed the application for world heritage status unless clear reference was made to the use of an estimated 60,000 labourers forced to work at seven of the sites, including the island coalmine Gunkanjima, during Japan’s 1910-1945 colonial rule over the Korean peninsula.

After the UN body’s 21-member panel in Bonn postponed a decision for 24 hours until Sunday to give the two sides more time to negotiate, Japan agreed to acknowledge the use of conscripted labour.

“Japan is prepared to take measures that allow an understanding that there were a large number of Koreans and others who were brought against their will and forced to work under harsh conditions in the 1940s at some of the sites,” the Japanese delegation to Unesco said in a statement.

Most forced labourers have died, but some survivors are still seeking compensation from Japan through the courts. Japan had initially resisted South Korean pressure, saying its application referred to a period up to 1910, before foreign labourers were put to work at the sites.

While South Korea’s government welcomed the agreement, after months of negotiations, politicians in Tokyo attempted to play down the significance of Japan’s concession.

“For the first time Japan mentioned the historical fact that Koreans were drafted against their will and forced into labour under harsh conditions in the 1940s,” South Korea’s foreign ministry said in a statement. “Given that this matter was resolved smoothly through dialogue, the government hopes it will help the further development of South Korea and Japan relations.”

After the UN body’s 21-member panel in Bonn postponed a decision for 24 hours until Sunday to give the two sides more time to negotiate, Japan agreed to acknowledge the use of conscripted labour.

“Japan is prepared to take measures that allow an understanding that there were a large number of Koreans and others who were brought against their will and forced to work under harsh conditions in the 1940s at some of the sites,” the Japanese delegation to Unesco said in a statement.

Most forced labourers have died, but some survivors are still seeking compensation from Japan through the courts. Japan had initially resisted South Korean pressure, saying its application referred to a period up to 1910, before foreign labourers were put to work at the sites.

While South Korea’s government welcomed the agreement, after months of negotiations, politicians in Tokyo attempted to play down the significance of Japan’s concession.

“For the first time Japan mentioned the historical fact that Koreans were drafted against their will and forced into labour under harsh conditions in the 1940s,” South Korea’s foreign ministry said in a statement. “Given that this matter was resolved smoothly through dialogue, the government hopes it will help the further development of South Korea and Japan relations.”

“The government’s position over those recruited from Korea has not changed,” the chief cabinet secretary, Yoshihide Suga, told reporters.

Local supporters celebrated the sites’ inclusion, which is expected to boost tourism and opens up sources of funding for preservation work.

“The value of our industrial heritage of what became the driving force of Japan’s industrial development has gained global recognition,” said Kenji Kitahashi, mayor of Kitakyushu city, where the Yawata steel mill used thousands of forced labourers. “I would like to share this joy with the residents of this city, and with the people of Japan.”

The chief objection to the Japanese sites’ inclusion came from China. “Japan has still not given an adequate account of all of the facts surrounding the use of forced labour,” China’s ambassador to Unesco, Zhang Xiuqin, was quoted as saying by the official Xinhua news agency.

Zhang urged Japan to ensure that “the sufferings of each and every one of the forced labourers is remembered, and their dignity upheld”.

More about: