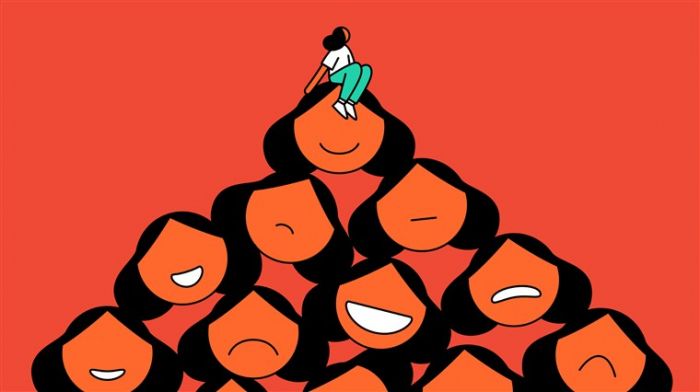

People who chronically brag and boast are grating – and, at times, repellent. But a surprising truth about narcissists might help us feel unexpected compassion for them.

In a world where humility is valued, some of the most grating people are those who constantly name-drop, brag, claim credit and opine about their brilliance. These qualities set off loud alarm bells of a narcissist in our presence – the kind of person who makes us roll our eyes and gnash our teeth.

It’s hard to find compassion for a someone who’s full of themself – and, in many cases, it’s unclear why we’d want to sympathise with the people who repel us most. However, research indicates that unlike Narcissus staring at himself reflecting in the pool, many narcissists actually aren’t in love with themselves after all.

Quite the opposite, in fact.

Much of the time, a narcissist’s behaviour isn’t driven by self-love – rather, self-hatred. New findings reinforce this idea, noting that narcissistic behaviour like flexing on social media might come from low self-esteem and a constant need for self-validation. The fact that some narcissists might actually dislike themselves not only debunks the common school of thought around braggarts, but also suggests that we might want to rethink the way we interact with narcissists.

'They don't feel good'

"Narcissists tend to be very charming and outgoing, and they can make very good first impressions," says Robin Edelstein, professor of psychology at the University of Michigan, US. "But they also tend to be somewhat disagreeable, lacking in empathy and manipulative."

In an employment setting, that can mean taking credit for other people's work, blaming colleagues for mistakes, taking advantage of others to get ahead or responding to feedback with hostility, explains Edelstein. Socially, this may manifest as showing off on social media, or usurping attention over brunch at the expense of someone else.

A common misconception is that this behaviour stems from intense self-love, self-obsession and self-centredness. But the cause could be just the opposite.

"Narcissistic individuals are actually really hamstrung by insecurity and shame, and their entire life is an attempt to regulate their image," says Ramani Durvasula, a licenced clinical psychologist and professor at California State University, Los Angeles. "Narcissism has never been about self-love – it is almost entirely about self-loathing."

It's long been established that there are two types of narcissists: "vulnerable" ones, who have low self-esteem and crave affirmation, and "grandiose" ones, who have a genuinely overinflated sense of self.

A new study from New York University shows that grandiose narcissists might not be considered narcissists at all, because their behaviour could resemble psychopathy – a related condition in which people act with no empathy in self-serving ways. The research team suggests vulnerable types are the true narcissists, because they don't seek power or dominance, but rather affirmation and attention that elevate their status and image in the minds of others.

"They do not feel good about themselves at all," says Pascal Wallisch, clinical associate professor at New York University and senior author of the study. "The paper is not to demonise narcissists at all – on the contrary, we need a lot more compassion."

The study involved nearly 300 undergraduate university students, who answered questionnaires that measured personality traits, like being insecure or unempathetic, with statements like "I tend to lack remorse" or "It matters that I am seen at important events". They found that unlike grandiose narcissists, vulnerable narcissists were the group who most manifested insecurity and other related traits.

So, when you see someone name-dropping at work, plastering selfies on Instagram or being touchy to feedback that makes them look bad, they could very well be a vulnerable (or "true") narcissist. Their constant need for attention and apparent obsession with self comes from deep insecurities they're trying to cover up.

A vicious cycle

Of course, seeking positive reinforcement to make ourselves feel better is something everybody does from time to time – and doesn’t necessarily make someone a narcissist.

"Seeking out self-enhancement is a normal aspect of personality. We all try to seek out experiences that boost our self-esteem," says Nicole Cain, associate professor of clinical psychology at Rutgers University in New Jersey, US. But narcissism can lead to "self-enhancement becomes the overriding goal in nearly all situations, and may be sought out in problematic and inappropriate ways".

In these cases, behaviours aimed at boosting external validation can backfire, because people end up liking the individual less. Wallisch calls the resulting cyclic, repetitive behaviour a "maladaptive cascade", a self-defeating cycle that comes in three phases. It starts off with a vulnerable narcissist fearing that others aren't perceiving them in a certain way – so then they self-aggrandise to alleviate that fear. But paradoxically, others are put off by the behaviour, leading the narcissist right back to square one – and, in fact, the other person might view them even less favourably than before. That's what interests Wallisch most: the narcissist clearly isn't being rewarded for this behaviour, but they do it anyway, because they mistakenly view it as a means of alleviating pain and fear.

"Narcissistic people have an idea of how they want to be seen, and don't feel they measure up to that," says Durvasula. "So, they have to portray themselves [in a certain way], and then because they behave badly to do that, they end up experiencing social rejection anyhow, and the cycle keeps happening."

For narcissists, "self-enhancement becomes the overriding goal in nearly all situations" – Nicole Cain

While this rarely ends in a good place, Wallisch suggests that "we can't take these behaviours at face value, especially if someone is boasting and blustering". He adds, "It doesn't mean they actually feel good about themselves. Something is lacking in their life." He says these kinds of vulnerable narcissists might actually hate themselves. "It's very sad and tragic. They feel like they are never going to be good enough. If they become a billionaire, that's not going to help with the [root] psychological issue."

Misunderstood and misnamed?

There's still a lot we don't know about narcissists in general, though. Some experts say the tug of war between self-love and self-loathing, and the idea they're self-promotional because they want to hide insecurities, doesn't fully explain the behaviour.

"This is a very hard question to test," says Edelstein. "How do you really know what a person feels deep down but is either unwilling or unable to express?"

It's also not clear how understanding what's driving narcissism will help curb the behaviour. Most narcissists don't realise that they are the problem, says Edelstein, something that makes tackling the issue hard. "Narcissists tend to be resistant to change because they see the locus of most problems in others rather than themselves," she says. "I think a person needs to be fairly self-motivated for any sort of intervention to be effective for any personality trait, but narcissism seems to be particularly sticky."

Cain, who suggests intensive psychotherapy is the best way to treat narcissism, says workers dealing with narcissistic colleagues should recognise that they are unlikely to be able to change them, persuade them or win an argument with them. "Set realistic expectations for your interactions with them. At work, clearly define roles. Don't get pulled into a competition with them," she says.

Remembering that their actions may well come from a place of insecurity could also help you view them with more compassion. "I think the best strategy for dealing with narcissists may be to try to understand where they're coming from," says Edelstein, "and that much of their behaviour comes from deep-seated insecurities and attempts to minimise their own vulnerabilities – as opposed to a reflection of your own inadequacies."

"I think people cover up mental pain quite a bit – by posturing, and other things," says Wallisch. "It's adds to the tragedy. They're misunderstood."

More about: