by Irwin Cotler, Ahmed Shaheed and Brandon Silver

Liberal democracies have not provided an adequate policy response to widespread and systematic state-sanctioned hate directed at many minorities. Rapid implementation of targeted sanctions against individuals inciting hatred and discrimination could possibly prevent further crimes.

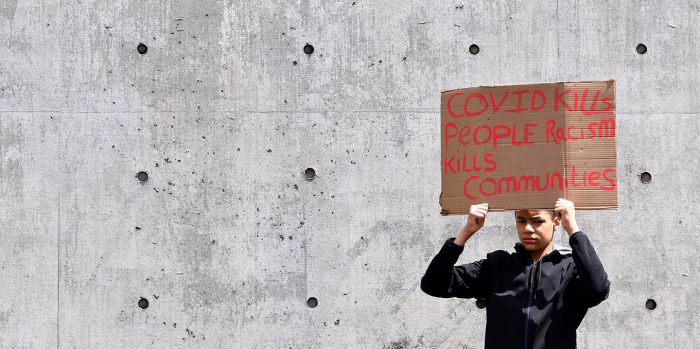

The COVID-19 pandemic has intensified the spread of an equally virulent virus: hate. Effective vaccines offer the best hope of defeating the coronavirus. We now need similarly targeted legal measures against those inciting hatred.

Today, a rapid worldwide resurgence of racism and xenophobia is targeting minorities like Jews, East Asians, and LGBT persons – with attendant harassment and physical harm – as being responsible for the spread of the coronavirus. In addition, some states have used the cover of COVID-19 restrictions and distractions to extend long-standing hateful policies.

This pandemic of hate long preceded the public-health pandemic, which exposed and expanded it. But despite this growing threat, far too many instances of hateful incitement go unaddressed, much less redressed, contributing to cultures of criminality and the impunity that underpins them. In particular, liberal democracies have not provided a commensurate and concrete policy response to the widespread and systematic state-sanctioned hate that continues to cause the misery, murder, and migration of many minorities.

Sadly, state-sanctioned anti-Semitism, anti-Muslim hatred, and bigotry against black and indigenous people are global phenomena. Emblematic examples of country-specific hate include the constitutionally enshrined discrimination and government incitement against Ahmadiyya Muslims in Pakistan, and the apartheid-like system of unjust imprisonments and dispossession of the Baha’i religious minority in Iran.

Worse, the perpetrators of these crimes continue to travel largely unimpeded around the world. Maintaining the status quo – decades of brutal persecution that shows no signs of abating – could best be described as complicity.

Combatting such hate is not only an ethical imperative, but also a public-policy one. Hate tears at society’s seams, and catalyzes crisis and conflict. This naturally progresses to mass atrocity. The Holocaust and subsequent genocides resulted not simply from a machinery of death, but also from an ideology of hate. The dehumanization of Tutsis as “cockroaches” by Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines planted the seeds of Rwanda’s killing fields in the 1990s in the same way that Joseph Goebbels’ anti-Semitic propaganda paved the path to the gas chambers of Auschwitz.

The world has long had a corpus of international laws intended to combat such crimes. After the horrors of the Holocaust, the international community crystallized a commitment to our common humanity in documents like the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and treaties such as the Genocide Convention, conventions on the elimination of racial discrimination and discrimination against women, and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. They recognize – and enshrine in law – the imperative of the struggle against hate and incitement, and the need to prevent and punish its manifestations, lest it metastasize.

But the implementation of human-rights foreign-policy tools based on these norms has been woefully inadequate, failing to challenge hate in the manner that it warrants. In particular, targeted sanctions frameworks such as Magnitsky Laws – nowadays the paradigmatic tool to punish human-rights abusers – have never been used expressly to combat incitement to violence and discrimination. This is despite many such frameworks being linked to the relevant international treaties, whether explicitly, such as in the European Union and United Kingdom, or implicitly, like in Canada and the United States.

Such sanctions have been a powerful post-facto tool, adding substance to statements condemning discriminatory violence against the vulnerable and – with applicable due-process safeguards – targeting the individuals most responsible for these crimes. They have been used, for example, in relation to Houthi-controlled security and intelligence agencies’ unjust detention and rape of politically involved women in Yemen, Chechen leaders’ torture and murder of LGBT persons, and the atrocities committed by Myanmar’s military, the Tatmadaw, against the country’s Rohingya Muslim minority. But these sanctions, while commendable, deal with the criminal consequences of hate, not its cause.

Rather than providing posthumous redress, targeted sanctions could possibly have prevented such crimes. Rapidly implementing such measures in response to incitement to hatred and discrimination – an initial early warning sign that often foreshadows major crimes – would sound the alarm and shine an international spotlight on the situation, naming and shaming individual perpetrators while providing protective cover to victims.

Moreover, sanctioning such individuals for incitement – typically with visa bans and asset seizures – could potentially serve as a deterrent, as they may modify their behavior in the hopes of being delisted. Even where those listed do not change their ways, targeted sanctions would reduce the virality of their hate by minimizing their resources and restricting their global mobility.

Such sanctions would be an important expression of solidarity and support for those suffering in other countries. Furthermore, they would safeguard the implementing country’s sovereignty by protecting against a corrosive influx of foreign assets and individuals linked to the promotion of divisive – and often deadly – discrimination.

Government leaders who violate internationally recognized obligations by promoting hate should not enjoy the freedoms abroad that they deny minorities at home. Protecting freedom of speech is not inconsistent with holding to account those inciting violence and discrimination. In fact, ending impunity for stirring up hatred would widen the scope for freedom of expression for all, especially for minorities whose voices are suppressed by rampant hate speech.

In these difficult and dangerous times, the shared desire for a peaceful and harmonious future, in which we celebrate our differences and the solidarity of humanity, can be a source of inspiration and a catalyst for global cooperation. To achieve it, we must stand up and strike out against the hate that ultimately hurts us all.

Irwin Cotler, a former minister of justice, attorney general, and member of Parliament of Canada, is Canada’s Special Envoy on Preserving Holocaust Remembrance and Combatting Antisemitism.

Ahmed Shaheed, a former foreign minister of the Maldives, is UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief and Deputy Director of the University of Essex Human Rights Centre.

Brandon Silver, an international human-rights lawyer, is Director of Policy and Projects and Head of the Global Magnitsky Sanctions Program at the Raoul Wallenberg Centre for Human Rights.

Read the original article on project-syndicate.org.

More about: