By Daphne Ewing-Chow

My hand trembled, uncertain, as I gripped the barrel of the pen, slowly scratching the letters “AB-positive” into the visitor log— each movement a jarring acknowledgment of the unspoken. My heartbeat pounded in my ears, drowning out the anticipatory purr of two ambulance engines idling nearby.

I was really doing this.

Only a month had passed since I met Heidi Kühn, the 2023 World Food Prize laureate and visionary behind NGO, Roots of Peace. For 25 years, the organization has transformed the scars of war into seeds of hope, working tirelessly to turn minefields into fertile farmland. Guided by the simple yet profound formula— demine, replant, regenerate— Roots of Peace has partnered with demining teams across the globe, restoring irrigation, infrastructure, and arable land to farmers in war-torn regions. It is a mission that reclaims not just soil, but the dignity and future of entire communities.

Heidi and I met at the Borlaug Dialogue— the annual food security conference of the World Food Prize Foundation in Iowa— and within minutes of our introduction, an unshakable bond formed.

When we discovered that we’d both be at the UN Climate Conference— COP 29— in Azerbaijan a few weeks later, Heidi extended an invitation that left me breathless in its audacity. “Join me,” she said, her voice alight with purpose, “in walking the minefields of Nagorno-Karabakh.”

The site of scarred lands ravaged by a decades-old territorial conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, Nagorno-Karabakh was once well-known for its verdant agricultural landscape. Its fertile soil and distinctive climate once supported a thriving agriculture sector, famous for its viticulture and an annual production of up to 160,000 tons of grapes— a testament to the region’s rich potential.

Heidi described a vision where landmine-ridden fields would give way to sprawling vineyards. “Mines to Vines,” she called it— with the fervor of a dreamer and the conviction of a mother— imagining lush grapevines where there was now only danger, imagining hope where there was despair.

“The grapevine is an ancient symbol of peace,” she said. “The fruit of the vine produces grapes, raisins and fine wine, which represents the seeds we have in common— rather than those which separate us.”

And so, there we were— a month later— packed into the back seat of a black International Eurasia Press Fund (IEPF) SUV, rumbling down a four-hour stretch of road from Baku to Aghdam. The gravity of what we were about to do was tempered by our shared laughter and whispered confessions. We clutched each other’s hands. Two mothers, hearts brimming with conviction, trading stories of our children— our shared humanity laid bare against the shadow of impending peril.

In the front passenger seat sat Umud Mirzayev, President of IEPF, a man whose quiet strength and humble resolve anchored the journey before us. More than the head of an NGO tirelessly advancing demining efforts and advocating for a safer Azerbaijan, he is a son of Karabakh, born into a family of grape farmers. His bond with Heidi, forged through shared purpose and a profound belief in renewal, had grown into a friendship as enduring as the land they both longed to see restored.

On one of her previous visits, they had knelt together in the soil at the IEPF offices in Tartar, symbolically planting a grapevine in soil long shadowed by war. The act was simple yet profound, a silent promise that even in the aftermath of destruction, life could begin anew. As our SUV rolled toward the perilous fields of Aghdam, Mirzayev’s steady presence carried the weight of that promise.

-1735029508.jpg)

Before us, Aghdam, once a vibrant urban hub, exposed the ugly scars of war. The brutal six-year battle that began in 1988 left Armenian forces in control, and renewed fighting in 2020, which lasted for 44-days, saw Azerbaijan reclaim much of the land. Remnants of homes, skeletal vehicles, and barren fields that mark the area had become haunting testaments to war’s devastation.

But beneath this ravaged site is a cradle of history where the roots of Azerbaijan’s ancient winemaking tradition run deep. Archaeological excavations near the city of Aghdam have revealed grape seeds and petrified clay jars that date back 3,500 years. This land, once home to vineyards that birthed native grape varieties unique to Azerbaijan, stands as a poignant reminder of what was lost— yet also of what might bloom again.

My discussions with Elchin Amirbayov, Special Envoy of President Ilham Aliyev, outline the war’s staggering toll. Azerbaijan is one of the five most heavily mined countries globally; over 1.5 million landmines and unexploded ordnance planted since the 1990s have contaminated 12,000 square kilometers— 13% of Azerbaijan’s territory. Over the last 30 years, the cumulative toll of landmine victims in Azerbaijan is in the thousands, with 382 victims recorded since 2020.

“This is not only about mines,” he said gravely, “but about innocent lives lost to this scourge.”

A devastating blow to Azerbaijan’s economy and food security lies in the vast, idle expanse of land— 60% of it flat, fertile agricultural fields— now deemed unusable by the lingering scars of conflict. According to a report from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “the presence of mines and other unexploded ordnance have significantly disrupted the land, vegetation cover, water infiltration, and the flow of water, and have rendered vast areas of valuable agricultural land inaccessible.”

At the ANAMA base in Saricali Village, Khalid Zulfugarov, the head of the ANAMA (Azerbaijan National Agency for Mine Action) demining unit in the area and Shahin Allahverdiyev, IEPF’s Operations Manager described the efforts underway to rebuild the city and restore it as a hub for regional development and resettlement.

As of mid-2024, over 145,700 hectares of land have been cleared, neutralizing more than 122,000 explosives, including 32,581 anti-personnel mines and 19,666 anti-tank mines. Despite these advancements, less than 13% of the contaminated region has been cleared, highlighting the immense scale of the challenge.

“Landmine clearance efforts are costly and require advanced technology, skilled labor, and sustained international support,” says Mirzayev. “Without urgent investment, the ongoing environmental degradation will continue to escalate, threatening biodiversity, natural ecosystems, and the livelihoods of communities who rely on these resources. Accelerating the pace of landmine removal is not just a humanitarian necessity but an ecological imperative to prevent further damage to our planet’s biosphere.”

In June 2021, a mine map from Armenia exposed the alarming presence of 97,000 mines in Aghdam alone. In 2023, under the coordination of ANAMA, the UNDP, in collaboration with IEPF, Mines Advisory Group (MAG), and APOPO, launched a project to mitigate the landmine threat and help to resettle the area. In 2024, this joint effort supported the deactivation of close to 3,000 mines in Aghdam alone.

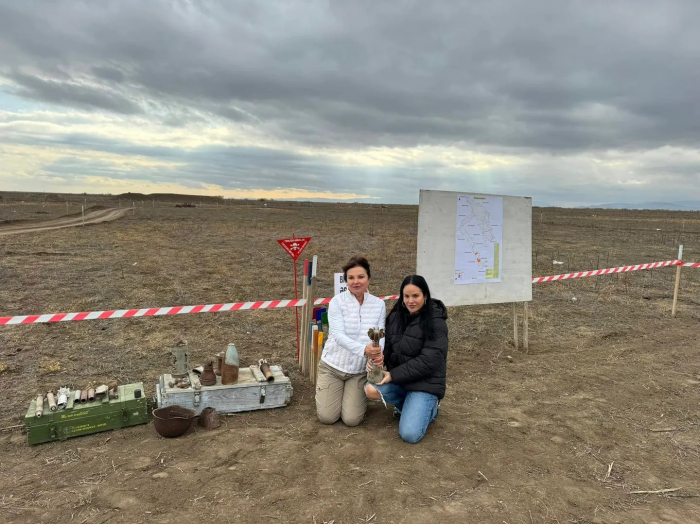

Through the desolate expanse of Aghdam, we arrived at a roped-off clearing in Namirli Village. Here, we provided our blood types, passed ambulances on standby, and stood before wooden crates filled with recovered remnants of conflict. It was here, too, that we met 14 male deminers, as they worked. Later, at the IEPF offices, we would meet nine women deminers— a quiet yet powerful testament to resilience and the shared determination to transform fields of danger into landscapes of hope.

In Namirli Village, under a small, makeshift tent, we clasped cups of scalding tea to thaw our cold fingers as Ramin Gadimli, of MAG, shared his story. Serving as both translator and witness, Ramin recounted the searing impact of the six-week war in 2020. Then a member of the Baku police force, and originally from Ismayilli where many young men were deployed as soldiers, he saw the brutal toll firsthand. “I lost many friends, and many others were badly injured,” he said, his voice steady yet burdened by the tragedy. “The news during that time was relentless and heartbreaking.” His words hung in the air, heavy as the work being done just steps away.

Ramin tells me that much of the land cleared by MAG around the world is agricultural, a reminder that demining is not just about safety and survival— it is also about sustenance. Once freed from the grip of hidden explosives, these fields can once again nourish communities, restoring livelihoods with dignity and purpose. Cleared land enables farmers to cultivate crops, rebuild irrigation systems, and revitalize local economies. Every mine removed is a step toward greater food security, unlocking the potential for sustainable development and resilient food systems in regions scarred by conflict.

According to a study reported in journal, Global Environmental Change, one third of all cases of agricultural abandonment in the Caucas region during post-Soviet times have been war-related, in part due to landmines.

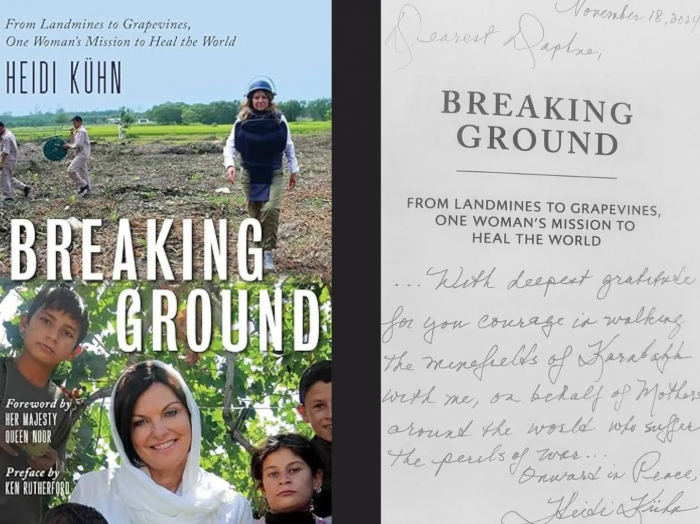

In her foreword in Heidi’s memoir, Breaking Ground : From Landmines to Grapevines, One Woman's Mission to Heal the World, Queen Noor refers to landmines as ‘“weapons of mass destruction in slow motion.” They continue destroying lives and livestock and holding valuable agricultural land hostage long after conflict has stopped.”

This is the legacy of war in Nagorno-Karabakh.

A year and a half before Heidi and I retraced what she called the “footsteps of peace,” she stood in Alfred Nobel’s private home in Baku, Azerbaijan, receiving the official news that she had been awarded the 2023 World Food Prize. Just two days earlier, she had wielded Nobel’s invention— dynamite— not for destruction, but for renewal, detonating six anti-tank mines in Nagorno-Karabakh. In that moment, history and purpose converged: a symbol of war transformed into a tool for reclaiming life.

In 2023, Azerbaijan declared “A world without mines” as its 18th National Sustainable Development Goal, aligning this bold vision with the UN Agenda 2030. Landmines are more than remnants of conflict; they are barriers to life itself, rendering fertile fields untouchable and severing the lifeline of food security for nations and communities alike.

Yet, the scale of the challenge demands global action. According to Elchin Amirbayov, foreign assistance has accounted for only 5% of the resources used for large-scale demining efforts since 2020. Greater international support is urgently needed to accelerate demining operations and enable the safe return of 800,000 internally displaced persons to their long-abandoned homes.

In Aghdam, across Nagorno-Karabakh, and in countless regions worldwide— where up to 110 million mines remain buried across 60 countries— the promise of renewal is etched into the soil, waiting to be healed.

Heidi and I were bound by an unspoken oath: to stand together in defiance of fear, to carve paths of safety where others dared not tread, and to carry forward the voices of those silenced by conflict.

It was a connection, raw and immediate— fueled by the hope of two mothers. Hope for the land. Hope for our children. Hope for a world where vines would one day flourish, strong and unyielding, in the place of mines.

The original article was published in Forbes.

More about:

-1735029322.jpg)