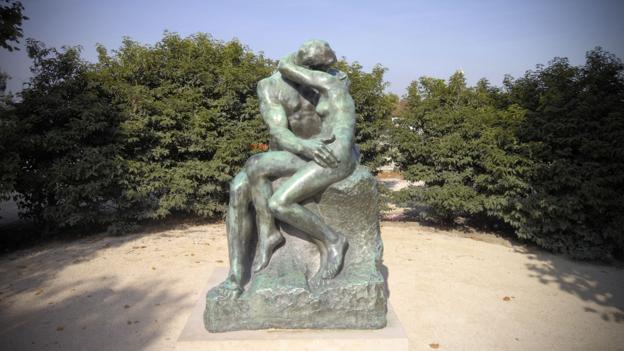

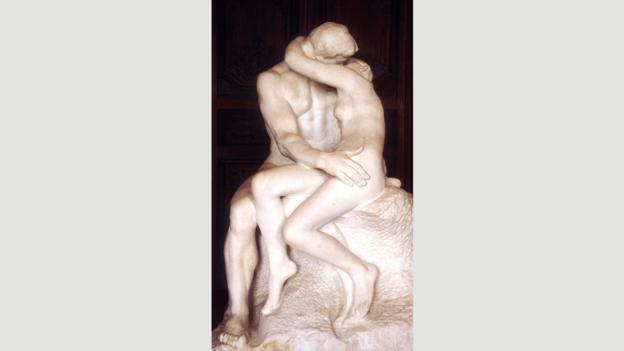

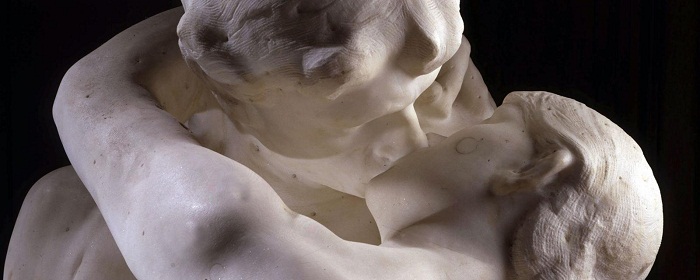

It must be one of the frankest – and most popular – images of carnal love in the history of art: Auguste Rodin’s monumental marble sculpture of two naked lovers fused in passion, known simply as The Kiss. With sleek and supple bodies, which provide a striking contrast to the roughly chiselled rock on which they sit, Rodin’s sweethearts appear timeless and idealised: a universal representation of sexual infatuation, oblivious to all else.

Three over-life-size marble versions of the sculpture were executed in Rodin’s lifetime. The earliest is in the collection of the Musée Rodin in Paris, which reopened this month following extensive refurbishment, in its home, the Hôtel Biron, a magnificent 18th Century palace that the sculptor used as his Paris studio until his death in 1917.

The museum was always one of the most romantic destinations in the city. Now spruced up, with refurbished woodwork and parquet floors, it remains so; indeed, its appeal has been enhanced. And, appropriately enough for this mecca for young lovers, The Kiss occupies a prominent position, immediately visible as you enter the building, in the middle of a gallery on the ground floor.

Yet while The Kiss seems so buoyantly optimistic, simple, and carefree, the story of its creation and afterlife offers a knottier tale. For instance, did you know that Rodin’s paramours actually represent a pair of doomed adulterers from Dante’s Inferno?

Doomed lovers

The origins of the sculpture can be traced to 1880, when Rodin, who had been born in a working-class district of Paris as the son of a police clerk, was approaching 40. By then, he had established his reputation. That year, he was commissioned for the first time by the French state to design a pair of monumental bronze doors for a new museum of decorative arts.

As a theme, he chose Dante’s Inferno. From the off, he planned to sculpt a pair of lovers in relief in the middle of the left-hand door panel. Called Faith, the group would represent the illicit passion of Paolo and Francesca, whom Dante met in the second circle of hell, buffeted by an eternal whirlwind, and who were a popular subject in 19th Century art.

According to the original 13th Century story, Francesca and Paolo fell for one another as they sat reading tales of courtly love. When Francesca’s husband, who was also Paolo’s brother, discovered them, he stabbed them to death. Rodin decided to depict the lovers at the moment of their first kiss. Look closely, and you can see the book slipping from the man’s left hand.

In the mid-1880s, though, the plans for the new museum foundered, and Rodin’s Gates of Hell, as they eventually became known, were not cast in bronze until after his death. By 1886, though, Rodin had decided anyway that his bas-relief of Paolo and Francesca would work better as a large, spiralling sculpture in the round – and the following year, the French state commissioned him to execute the work in marble on a scale larger than life.

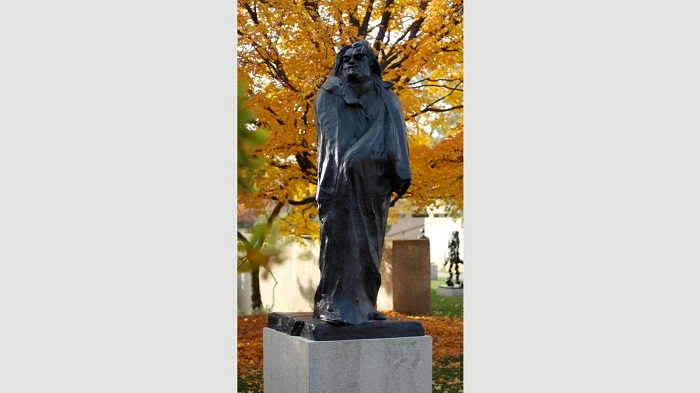

For the next decade, The Kiss stood unfinished in Rodin’s studio, as he focused his attention elsewhere. In 1898, though, Rodin decided to exhibit it at the annual Salon, alongside his monolithic statue of the writer Honoré de Balzac, which the art historian and Rodin scholar Catherine Lampert describes as the artist’s “most radical work”.

While the latter sculpture, in which the writer stands shrouded in a robe covering a strangely priapic bulge, was ridiculed, The Kiss proved a hit with the public at once. It was quickly copied in bronze in various sizes, and more than 300 casts had appeared by 1917. “It is a magnet for thoughts of romantic, physical, youthful passion,” explains Lampert.

In 1900, the gay Bostonian antiquarian and connoisseur Edward Perry Warren, who lived in East Sussex in southern England, enquired whether Rodin would consider producing a full-size replica of the sculpture “in the finest possible marble” for his own private collection. The French artist acquiesced and a contract was drawn up, specifying Rodin’s fee of 20,000 francs, as well as the stipulation that “the genital organ of the man must be completed”. The finished piece was delivered in the summer of 1904, but it proved too large for Warren’s house and had to be stored, ignominiously, in the stable block.

During the First World War, Warren loaned it to Lewes Town Hall: “It was installed in the Assembly Room,” says Lampert, “which was a recreation space for troops billeted in the town. Regular boxing matches were staged in the room.” But the indecency of its nude protagonists proved so offensive to puritanical locals, who feared that it would incite lewd behaviour among the soldiers, that it was surrounded by a railing and covered with a sheet. Two years later, it was returned to Warren and hidden by hay bales, to protect it from shells. Eventually, long after Warren’s death in 1928, it entered the collection of the Tate, in 1953.

All tied up

Half a century later, The Kiss was causing controversy in Britain once again. For years, it had occupied the central rotunda in what is now Tate Britain, but, following the opening of Tate Modern in 2000, it was moved to the new gallery, where it languished on a landing near the toilets.

When the British artist Cornelia Parker was invited to participate in the Tate Triennial in 2003, she decided to return The Kiss to its “prime spot” in Tate Britain, wrapped up in a mile of string. This was a reference to an infamous wartime show of Surrealism in New York designed by the modern artist Marcel Duchamp, who criss-crossed the exhibition space with a “mile of string”, so that his tangled web would obscure the other artworks.

“It was like a battle between two styles,” Parker explains, referring to her own intervention, which she called The Distance (A Kiss with String Attached). “I’ve always loved Rodin, but I probably love Duchamp more. And I felt that even though it was the most famous sculpture in the Tate – people love it – The Kiss had become a bit clichéd. I wanted to give it back the complication it used to have: that relationships can be tortured, and not just this romantic ideal. So the string stood in for the complications of relationships.”

Not everybody was enamoured with Parker’s idea. Negative articles quickly appeared in the press: “Some of it was quite painful, but it didn’t surprise me,” Parker recalls. “Perhaps it seemed a very arrogant thing for me to be doing.” One irate visitor to the Tate even whipped out a pair of shears and chopped off Parker’s string before the guards could intervene. The Tate wanted to prosecute, but Parker didn’t wish to give any more oxygen to the assailant’s cause. “Instead I just tied the string back together and put it back on,” she says, “and that made it even less lyrical and slightly more punk. I imagined that Duchamp would have enjoyed that, so I thought I should enjoy it too. Actually, it’s one of my favourite pieces I’ve ever done.”

Of course, the conceptual art that Duchamp pioneered during the first half of the 20th Century could not have been more different from Rodin’s easy-on-the-eye forms. Yet Rodin, too, was a great innovator. “His imagination was fired by immediate proximity to the men and women who posed for him,” Lampert explains, “and his modelling in clay of their bodies, turned 360, is still breath-taking and unsurpassed.” Moreover, she continues, “He was one of the first artists to be curious about the sexual experience of women.”

To a degree, this is evident in The Kiss, in which the woman reciprocates the active sexual desire of the man. (It was rumoured that the inspiration for the woman in The Kiss was Rodin’s mistress, the sculptor Camille Claudel, but the sculpture was begun before they had met.)

Yet Rodin’s curiosity about female sexuality is even more apparent in other, more explicit works of art displayed at the Musée Rodin, such as the startling Iris, Messenger of the Gods (c 1895), in which a headless naked woman hurtles through space in mid-air. In a gesture that may allude to the titillating routines of can-can dancers, her right hand clutches her foot, so that her legs are splayed to reveal her sex.

The Kiss isn’t nearly as provocative. If anything, it is a cleaned-up, tasteful rendition of desire – a kiss, not an orgasm. Perhaps this is why Rodin himself was dismissive of it: he once called The Kiss “a large sculpted knick-knack following the usual formula”. Yet – like Parker’s mile of string – knowing about the backstory of the sculpture complicates our response to it, in, I believe, a useful and stimulating way. Perhaps the old adage is right: despite appearances to the contrary, the course of true love never does run smooth.

More about:

-1745485667.jpg&h=190&w=280&zc=1&q=100)