The same goes for other people’s faces, says Linda Henriksson at Aalto University in Helsinki, Finland. Her team scanned 12 people’s brains while they looked at hundreds of images of noses, eyes, mouths and other facial features and recorded which bits of the brain became active.

This revealed a region in the occipital face area in which features that are next to each other on a real face are organised together in the brain’s representation of that face. The team have called this map the “faciotopy”.

The occipital face area is a region of the brain known to be involved in general facial processing. “Facial recognition is so fundamental to human behaviour that it makes sense that there would be a specialised area of the brain that maps features of the face,” she says.

This is the first example of a brain map that reflects the topology of an object in our environment, says Henriksson.

Who’s that in my toast?

The finding raises the question of whether differences in faciotopy could explain why some people struggle with face processing, such as those with prosopagnosia, says Brad Duchaine, a cognitive neuroscientist at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire. The team plan to investigate differences in face recognition and faciotopy next.

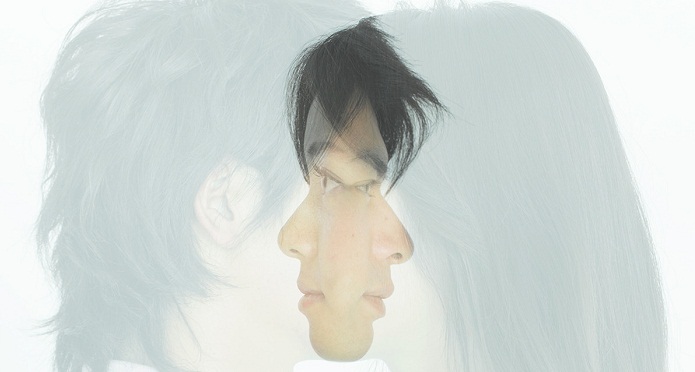

For most people, faces demand very little attention from the brain in order to be recognised. So little, in fact, that we often see faces where they don’t exist – Jesus in our toast or the man in the moon, for example. Earlier this month, the internet went into a frenzy over a demon lurking over a baby in an anonymous woman’s ultrasound.

“We can’t help but see faces everywhere,” says Winrich Freiwald, who studies face processing systems at the Rockefeller University in New York. It’s a result of specialised face cells in the brain responding to non-face objects that share certain feature with faces, he says.

“Face recognition is such an important mechanism that it’s fooled by stimuli that resemble the two-eyes, nose and mouth combination”.

-1745485667.jpg&h=190&w=280&zc=1&q=100)