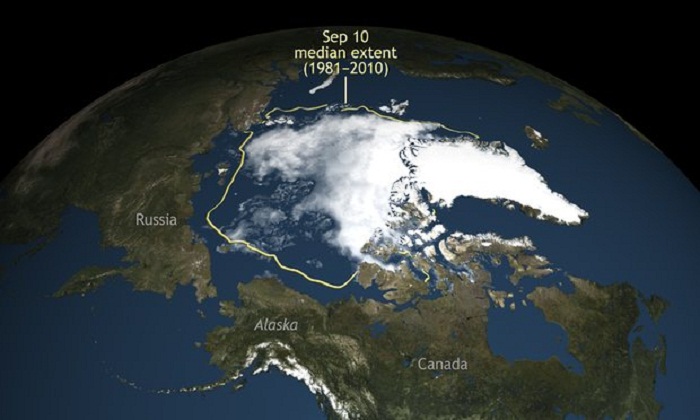

Depending on how the weather plays out over the next few weeks, that minimum is likely to fall somewhere between second and fifth place, they estimate — still a remarkably low level that shows how precipitously sea ice has declined in recent decades.

“There hasn’t been any recovery in any ice at all,” Julienne Stroeve, a senior scientist at the National Snow & Ice Data Center, said.

The area of the Arctic Ocean covered by sea ice naturally waxes and wanes with the seasons, reaching its peak at the end of winter and its nadir at the end of summer, usually in mid-September.

But the steady increase in heat-trapping greenhouse gases in the Earth’s atmosphere has fueled an intense warming of the Arctic region; temperatures there are rising at twice the rate as the global average. That has caused a dramatic melting of the sea ice that floats atop the frigid ocean waters.

Since the beginning of satellite records in 1979, the winter peak has declined by 3.2 percent per decade, while the summer minimum has declined by 13.7 percent per decade.

That loss of ice has significant ramifications for the animals that depend on it for access to food and coastal communities that need it for protection from intense Arctic storms. The loss of ice has also fueled interest in opening shipping routes through the region, as well as exploiting natural resources, such as oil, found beneath the seafloor.

But the effects of melt aren’t confined to the Arctic: Ice reflects the sun’s rays, so as it disappears, more ocean waters, which absorb those rays, are exposed, intensifying regional and global warming. Some research also suggests that the loss of ice could be impacting extreme weather in Europe, Asia and North America.

This winter, Arctic weather stayed remarkably warm, to the extent that it surprised even veteran sea ice researchers. That balmy weather stymied sea ice growth and caused sea ice extent to hit a record low winter peak for the second year in a row.

As the sun rose with the coming of spring, that meant more open ocean was exposed and ready to absorb the sun’s rays, fueling an early start to the melt season. By May, the melt season was two to four weeks ahead of schedule andfar below the previous record low for the month.

But even such a huge head start didn’t guarantee a record low come summer’s end, because weather plays a key role in summer melt. Beginning in June and lasting through July — the peak months of sun exposure — Arctic weather turned cloudy and somewhat cooler.

“So that dropped us off the pace pretty quickly,” Walt Meier, a NASA sea ice scientist, said.

Exactly where this summer’s minimum falls depends on what the weather does over the next few weeks. For example, winds could influence where sea ice flows, potentially compacting what is left, or further breaking up already tenuous chunks.

With the sun dropping ever lower in the sky, it has less influence over that melt, but the warmth retained in the ocean will continue to eat away at the ice for a few weeks.

A record low is virtually out of the question, though.

“I don’t see how we could catch 2012,” Meier said. “There’s not enough time left in the season.”

He does think it’s possible that this year could overtake 2007’s low, the second lowest extent on record.

The potential to take the second place spot, despite the fact that “the summer was just not really conducive to extreme melt” shows just how far sea ice has fallen, Meier said. “That’s just in a lot of ways kind of remarkable.”

Sea ice levels as low as current ones would have stunned scientists even a decade ago. Now it has effectively become a new normal.

“Things have really changed,” Meier said. “The Arctic is very different.”

In a recent study in the journal Geographical Review, researchers compiled historical records of sea ice from ships’ logs and other sources and found that sea ice hasn’t been this low in at least the last 150 years. The rate that sea ice is declining is also unprecedented over that timespan.

However, despite some recent reports that the Arctic would be ice-free in the summer in the next year or two, that is not the case, Stroeve said. Most projections suggest that that point will be reached sometime in the middle of the century, and, as another recent paper found, scientists’ ability to pin down that date is limited by the natural variability of the sea ice system to within a couple of decades.

Any prediction of ice-free conditions in the next few years doesn’t take into account the physics of the system, Stroeve said.

“I agree it’s going to go away eventually,” she said. “But it’s not there yet.”

More about: