“If plumes exist, this is an exciting find,” lead researcher William Sparks said. “It means we may be able to explore that ocean, that ocean of Europa, and for organic chemicals,” he added. “It would allow us to search for signs of life without having to drill through miles of ice.”

The apparent plumes seem to be mostly around the south pole, Sparks said, although one appears farther north and may be a likelier candidate for a mission. “We presume it to be water vapor or ice particles because that’s what Europa’s made of, and those molecules do appear at the wavelengths we observed.”

With other instruments, he said, the scientists could search for hydrogen, oxygen and other chemicals that could hint to what the ocean is made up of.

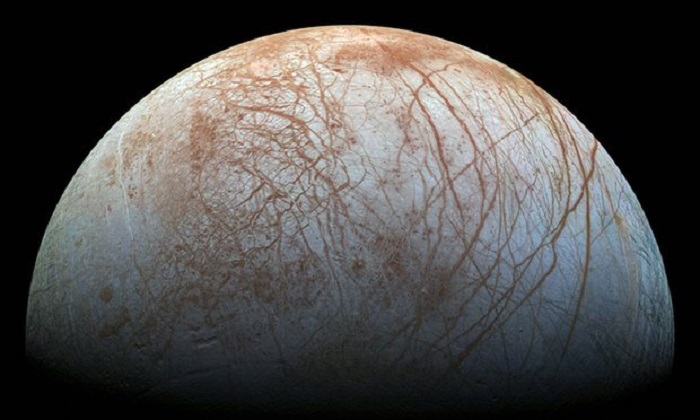

Europa is one of the most active bodies in the solar system: about the size of Earth’s moon, and at its warmest only about -260F (-160C), and covered in an icy shell that makes one of the most reflective objects in the neighborhood. But the moon also has rarer qualities: evidence of abundant liquid water, a rocky core that would have a range of chemicals, and energy generated by tidal heating – the moon is tidally locked to Jupiter, with one face always toward the gas giant.

Should the moon have water, energy and organic chemicals, it could have the basic building blocks that developed into life on Earth. “For a long time humanity has been wondering whether there is life beyond Earth,” Nasa astrophysicist Paul Hertz said. “We’re lucky enough to live in an era where we can address questions like that scientifically.

“We have a special interest in any place that might possess those characteristics. Europa might be such a place.”

The finding, Nasa’s astrophysicist Paul Hertz said, “increases our confidence that water and other materials in Europa’s ocean, Europa’s hidden ocean, might be ... available for us to study without us landing and digging on those unknown miles of ice”.

Scientists have collected clues for decades of an ocean beneath Europa’s icy shell. In 1979, Voyager spacecraft showed that the ice was cracked in some places, like ice floes on Earth, and the 1990s Galileo mission, which spent eight years orbiting Jupiter, confirmed the ocean under Europa. A 2016 study suggested that Europa produces 10 times more oxygen than hydrogen, and a 2014 study suggested the moon may have plate tectonics, qualities that would make it like Earth.

Nasa scientists have been working on proposals for a Europa mission for 15 years, and has a tentative plan to send a spacecraft on a flyby near the moon in the 2020s, zipping past its intense, electronics-frying radiation field. The ESA has also planned a mission to launch the Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (Juice), which will aim to orbit the moon Ganymede and collect data and Europa and a third moon, Callisto.

“The Europa flyby is not a life-finding mission,” said program scientist Curt Niebur. “That mission is focused on finding the habitability of Europa.”

Neibur said that Nasa was well versed in evaluating habitability, but had little in its history evaluating for life. “When it comes to finding life we don’t have as much experience, and we have an ongoing and vigorous debate in the scientific community when it goes to finding out.”

Sparks and Hubble scientist Jennifer Wiseman similarly downplayed the chances that a flyby mission could find direct evidence of life. “By the time it gets into space, with radiation and cryogenic temperature, it’s not going to survive,” he said.

“The jury’s out,” said Wiseman. “It first depends on whether the plumes are really there.”

Should the plumes exist, a spacecraft orbiting Europa could collect samples from plumes to get a taste of what Hertz called “a global saline liquid water ocean” that “engulfs the moon at the present time, hidden under miles of ice”.

Last year Nasa’s Cassini spacecraft dove into the plumes erupting from Saturn’s moon Enceladus, finding ice and dust that revealed qualities of the moon’s ocean. “It has revealed a tremendous amount of information about the ocean that is present beneath Enceladus’ ice shell,” Hertz said. “We would kill to have that kind of information and data about Europa.”

Sparks said the observations announced today were actually made in 2014, only a year after Nasa researchers saw what they believed to be evidence of water vapor plumes shooting 120 miles into space from Europa’s south pole. “It’s not just taking a picture,” Sparks said. “It’s a rather complicated way of observing.” He said that engineers had to develop the software to analyze a table of observed events, about 50 miles in total, and that the researchers continued to observe the moon throughout.

Sparks said that they had found statistically significant results, but cautioned: “We do not claim to have proven the existence of plumes but rather to have contributed evidence that such activity may be present.”

More about: