The Early Netherlandish painter’s artwork (c. 1490-1510) is a vision of sin and morality: and the devil is in the detail. As the art critic Alastair Sooke wrote in BBC Culture, The Garden of Earthly Delights has been called ‘probably the most famous scene of the underworld in all Western art’. If hell is other people, Bosch’s version involves people cavorting with owls, strawberries – and derrières tattooed with musical scores.

“I decided to transcribe it into modern notation, assuming the second line of the staff is C, as is common for chants of this era,” Hamrick wrote on her blog, before promptly going viral. The 500-Year-Old Butt Song from Hell, as it’s also known, is an entrancing piece: played on lute, harp and hurdy-gurdy or sung in a Gregorian choral arrangement, the music soars beyond a tiny patch of paint on the third panel of a triptych. And that is where Bosch’s genius lies: in among what appears to be a sweeping panorama encompassing Eden, a place of hedonistic abandon and Hell, small details pop up to reveal the unexpected.

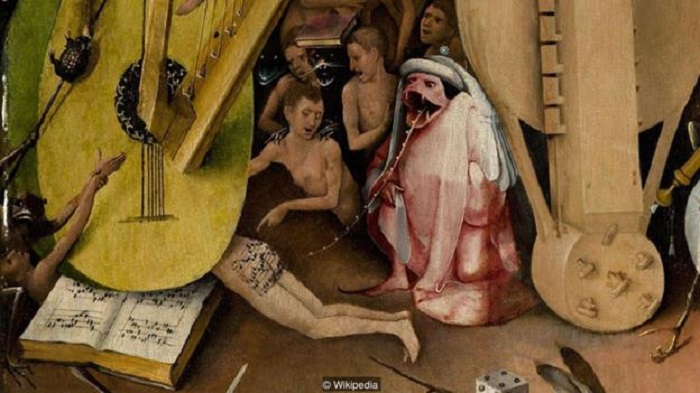

Gamblers

Torture, mutilation – and backgammon. One area of the painting’s third panel shows diabolical creatures stabbing a man in the back and impaling a heart on a sword, as well as dice and board games. The grotesque figures aren’t just inflicting pain; they’re gambling with their victims. According to an interactive tour of the painting created as part of a ‘transmedia triptych’ including the new documentary Jheronimus Bosch, Touched by the Devil, “Bosch’s hell panel is a far cry from other mediaeval depictions of inferno, where we often see people being boiled, burned or eaten alive. The suffering going on in this panel is not just on the physical level, it’s also psychological: the souls are being driven mad by fear, anxiety, chaos and distress”.

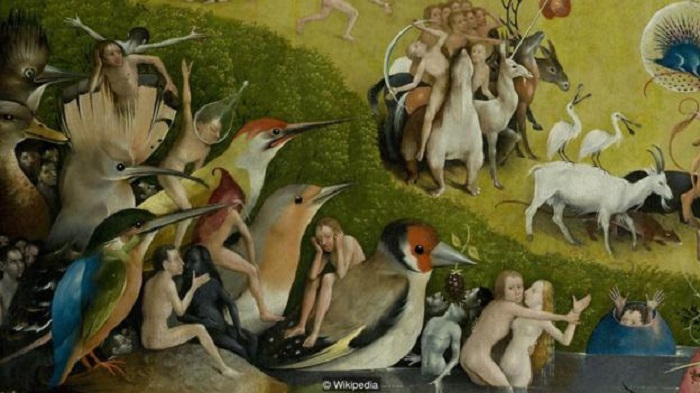

Birds

Alongside the suffering, there is humour. In the central panel, we see naked people riding oversized birds including a robin, a duck and a woodpecker. Bosch might have been making a visual joke: according to the interactive tour, “the birds could also be taken as a double entendre. As well as being an obsolete plural form, the Dutch word ‘vogelen’ (vogel meaning bird) could refer to having sexual intercourse”. There are other hidden messages to decode: art critic Kelly Grovier has written in BBC Culture about an “Easter egg that’s concealed in plain sight: the secret symbol that centres the eye… to find it, one’s eyes need merely draw an ‘X’ from the four corners of the work and an egg marks the spot, smack before us at the dead centre of the painting”. Despite depicting damnation, the painting is playful. According to Sooke, “Bosch has a reputation, above all, as the preeminent image-maker of hell… It seems he found jubilation in his peculiar creations, as well as fire and brimstone”.

Mussel shell

The Garden of Earthly Delights was first documented in 1517, when the Italian canon Antonio De’ Beatis, who was accompanying the Cardinal of Aragon on a visit to Brussels, wrote in his travel journal that “there are some panels on which bizarre things have been painted. They represent seas, skies, woods, meadows, and many other things, such as people crawling out of a shell, others that bring forth birds, men and women, white and black doing all sorts of different activities and poses”. Writing in A Dictionary of Sexual Language and Imagery in Shakespearean and Stuart Literature, Gordon Williams suggests that shellfish have been ‘venereal symbols’ since ancient times, arguing that although Bosch’s shell is from a mussel rather than an oyster, “it has a scattering of semen pearls… Pliny mentions a species of mussel called Venereae, or Venus-Shell”.

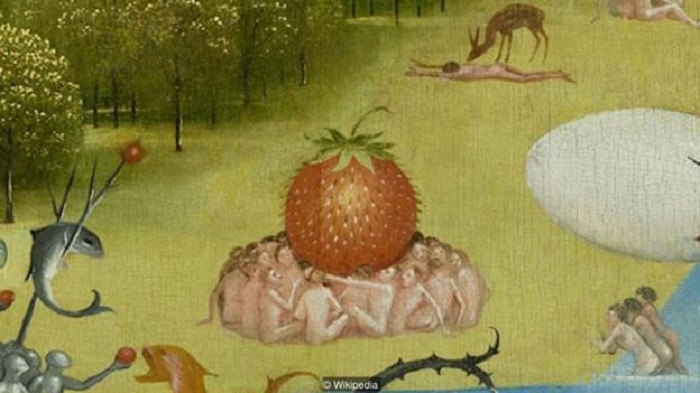

Strawberries

Early descriptions of the triptych refer to it as the ‘strawberry painting’, and the fruit appears several times in the central panel. It allows Bosch to reference other forms of imagery: in one section, people pick apples from trees while a man offers a strawberry to a woman with a leering expression, a twist on biblical depictions of Eden. In another, couples feed each other berries, a scene traditionally associated with courtly romance, yet here they are doing more than merely flirting. According to one critic, Bosch ‘subverts and perverts’ the theme of courtly love, with “‘love fruit’, a traditional metaphor for amorous union, both religious and worldly, now transformed into a hellish prison”.

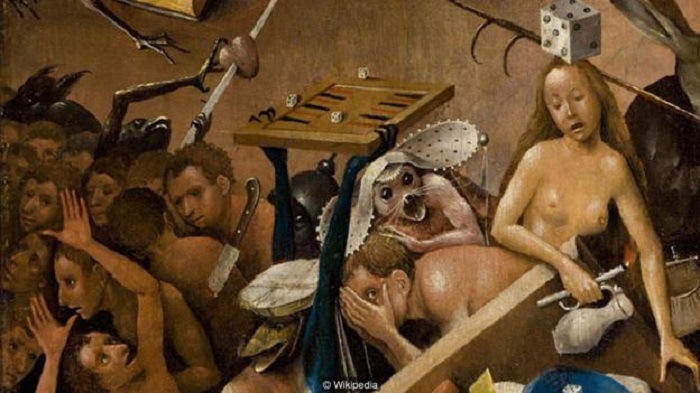

Pig nun

It might seem that the pig in a nun’s habit is the most significant element of this detail: but the amputated foot in fact offers the more surprising insight. Bosch paints the sawn-off appendage as a reminder of a condition known as St Anthony’s Fire – gangrene caused by eating bread infected with a black mould, or ergot fungus. In the 1950s, a component of the fungus was synthesised to create LSD. According to Pieter van Huystee’s interactive documentary, “If you ate bread from the wrong baker… limbs would rot away while the mind would be addled by hallucinations, ultimately leading to insanity. Did Hieronymus Bosch paint his Garden of Earthly Delights while suffering from a bad trip?”

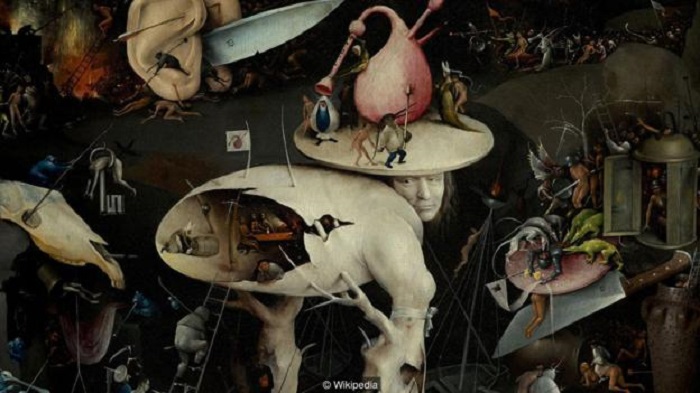

Tree Man

Hans Belting – who sees the painting as utopian rather than apocalyptic – believes that this figure is a self-portrait of Bosch. Art historian Reindert Falkenburg argues that the painter’s anthropomorphic images are ‘double’ or Gestalt, requiring an imaginative response by the viewer to see the veiled imagery. Ultimately, The Garden of Earthly Delights evades analysis. According to Falkenburg, it’s a work deliberately designed to resist interpretation; while Erwin Panofsky claims in Early Netherlandish Painting that “In spite of all the ingenious, erudite and in part extremely useful research devoted to the task of ‘decoding Jerome Bosch’, I cannot help feeling that the real secret of his magnificent nightmares and daydreams has still to be disclosed. We have bored a few holes through the door of the locked room; but somehow we do not seem to have discovered the key”.