“Where the tumor started doesn’t matter. What matters is why the tumor started,” says study coauthor Richard Goldberg, an oncologist at West Virginia University Cancer Institute in Morgantown.

People with defective DNA spell-checkers accumulate many mutations in their cells, which can lead to cancer. While mismatch repair errors can spark cancer, they may also be its Achilles’ heel: Some misspellings cause the cancer cells to make unusual proteins that the immune system uses to target tumors for destruction.

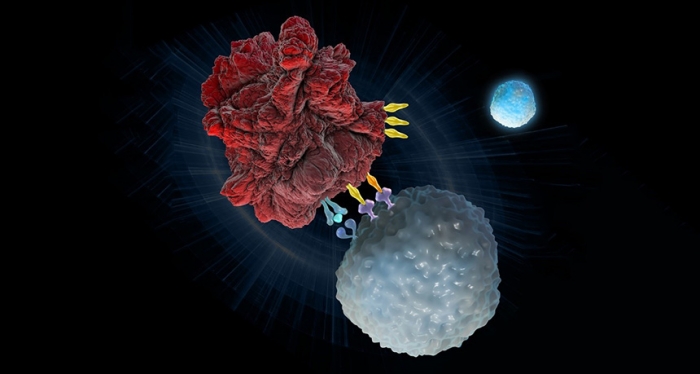

Even before treatment, cancer patients in the study had a small number of infection- and tumor-fighting T cells that target these unusual proteins, the researchers found. Treating patients with an antibody called pembrolizumab (sold under the brand name Keytruda) caused these T cells to increase in number, says coauthor Kellie Smith, a cancer immunologist at Johns Hopkins University.

The antibody binds to a protein on the surface of T cells called the PD-1 receptor. Some tumor cells use this receptor to hide from the immune system (SN: 4/1/17, p. 24). Blocking the receptor with the antibody unmasks the tumors. As a result, “immune cells can go to all corners of the body and eradicate tumors,” Smith says. That includes going after notoriously deadly metastatic tumors — ones that have spread from other parts of the body. Once the T cells are primed for action, they may patrol the body for a long time, stopping cancer from taking hold again, Smith says.

All 86 patients in the study had metastatic cancers that had not responded well to other treatments. For 18 patients, the antibody treatment appears to be a complete cure. Their tumors disappeared entirely. After two years of treatment, 11 of those patients were taken off the antibody. Their tumors have not returned even after a median of 8.3 months.

Other patients had tumors that shrank but didn’t disappear, or that remained stable while on — and even after — treatment. Goldberg says scans suggest some of the patients still have tumors, but biopsies show no remaining cancer cells. The “tumors” are really clusters of immune cells that have invaded sites to kill cancer, he says.

Not everyone fared so well. Tumors in five patients initially shrank, but then began to grow again. DNA from three of those people showed that two had developed mutations in the beta 2-microglobulin gene, which helps immune cells track down their targets.

Side effects of the treatment included skin rashes, thyroid problems and diabetes as the therapy caused the immune system to attack other parts of the body.

Revving up the immune system to combat a wide variety of tumor types may take cancer therapy in a new direction, says Khaled Barakat, a computational scientist at the University of Alberta in Canada, who was not involved in the study. In recent years, scientists have devised drugs to target specific mutations in one type of cancer. “That’s old school,” Barakat says. Immunotherapy “is the future.”

On May 23, the Food and Drug Administration approved pembrolizumab for advance-stage cancer patients with mismatch repair mutations for whom other drugs have failed. In the United States, about 60,000 late-stage cancer patients each year could be eligible for the immune therapy, the researchers estimate.

More about: #science