Until, that is, Angela Merkel won the dubious honour of becoming the first German Chancellor since World War Two to fail to form a government.

"What next, Germany?" is the favourite screaming front page headline of the moment here; the question ricocheting across the country from the federal parliament to queues at local bus stops and on endless TV chat shows.

Germans have been rubbing their eyes, still not quite able to believe that their normally staid mainstream politicians may now be hurtling towards an unruly, unexpected snap election.

But not if Germany's president can help it. Frank-Walter Steinmeier fears a new vote will only benefit the far-right.

He's now ensconced himself in back-to-back meetings with individual political parties, with a hefty dose of arm-twisting and pressure exertion on the agenda.

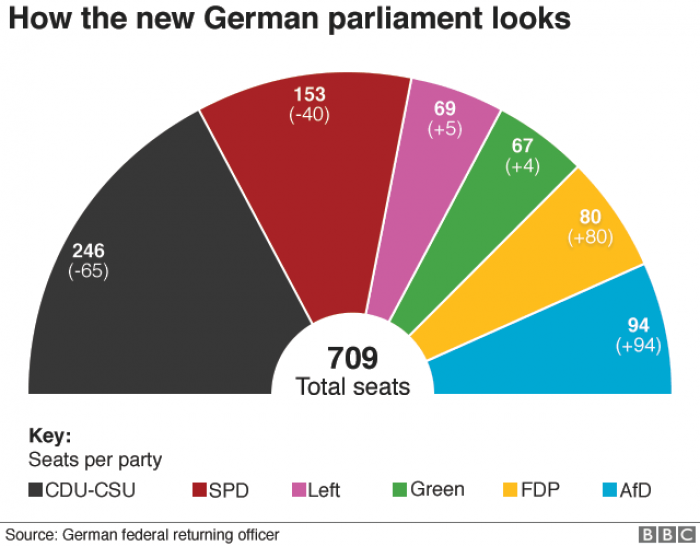

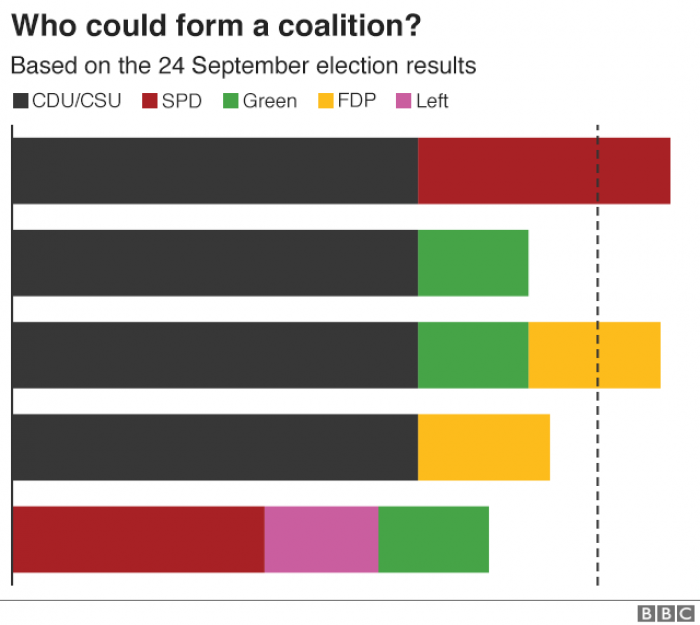

Today it's the turn of the Social Democrat Party (SPD) to go into the presidential den. The SPD is currently in caretaker government with Angela Merkel's conservatives.

Expect a clash of wills between the German president - an SPD man himself - and party leader Martin Schulz, who has ruled out going back into a GOKO (what Germans have dubbed the "grand" centre-left/centre-right coalition that has governed German for eight of the last 12 years).

Since talks to form a new government collapsed early on Monday morning, Mr Steinmeier and the new speaker of the German parliament - the former finance minister, Wolfgang Schäuble - have peppered their speeches with talk of duty and responsibility.

In tones designed, you might say, to trigger the kind of Lutheran sense of guilt the political old guard here may still be receptive to.

The two men have appealed to grandstanding political players in Germany to work towards forming a government, putting party politics aside for the good of the nation and, they've argued, for the good of Europe too.

Wolfgang Schäuble (L) and German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier (R)

The German establishment is painfully aware that others outside the country are also rubbing their eyes in disbelief at the political crisis here.

President Macron, for one, is stunned. Without Angela Merkel and the economically powerful and politically influential Germany at his side, his vision of an ambitiously reformed Europe will remain just that: a vision.

Europe's elite is dismayed across the board. It was gradually regaining confidence after the shock of the Brexit vote.

Things had seemed to be swinging the EU's way with a stronger euro, less support for populist nationalists, plus plans for reforming the eurozone, asylum policy and new cross country co-operation in defence.

But all this requires Germany in the European driving seat, not tinkering in the garage back home.

And what about Brexit?

Well, that's difficult to predict with any certainty.

A contact close to Angela Merkel told me her coalition-building difficulties wouldn't affect Germany's Brexit stance. Certainly the main political parties here are of a mind when it comes to the Brexit divorce issues.

But when it comes to talk of trade and transition, Angela Merkel will be missed if she loses her job or is politically distracted for months on end.

Yes, she is a stickler for rules but Mrs Merkel is also a pragmatist.

She hopes for a good Brexit deal for two main reasons: to benefit German business and also to help keep Europe stronger, by keeping the UK close as she apprehensively views Russia, Iran, North Korea and an unpredictable US under Donald Trump.

The British government has called for creative, imaginative thinking, resulting in an ambitious Brexit deal but for that you need political will and political clout on the EU-side.

No single voice is louder in EU circles than Germany's and Angela Merkel's. If she is silenced politically, that will have a knock-on effect beyond German borders.

So is she finished?

There's talk here of "Merkel-Dämmerung", literally 'the Merkel twilight', meaning the petering out of the Merkel era but I wouldn't write her off just yet.

She's a seasoned political fighter who has already served three terms in office and has as good as said she'd be damned if she was going to give up now.

But this is certainly the biggest crisis of her career.

Once dubbed the Queen of Germany and even the Empress of Europe, the extent to which her crown has slipped was painfully obvious as she was forced (through smilingly gritted teeth) to patiently answer repeated questions on German TV as to whether she was the political equivalent of yesterday's toast.

But Mrs Merkel still enjoys personal popularity ratings many EU leaders would dream of and she knows full well her party has no other viable candidate for chancellor.

According to a poll by Forsa, 45% of Germans favour new elections. Mrs Merkel says, if no coalition can be formed, she too favours that option over heading a minority government.

So it's a real possibility.

For many young Germans it's a thrilling prospect.

Frustrated with consensus politics which they view as safe and boring, they hope this could be the beginning of a political earthquake in Germany - a bleeding out of those they see as the fuddy-duddy old guard.

They want German politicians to obsess less about avoiding debt and instead to invest more in their own country - to improve roads and rail services and poor internet connections outside the big cities.

Germany has the lowest infrastructure investment rate of any big, rich economy.

The irony here is that, if this is the start of a German political revolution, it comes at a time when the country has never had it so good economically - with booming exports and a fat federal budget surplus - and when Europe, faced with international uncertainties, relies more than ever on strong and stable German leadership.

Michal Katya Adler is a British journalist, who works for the BBC, is now its Europe Editor.

The original article was published in BBC.