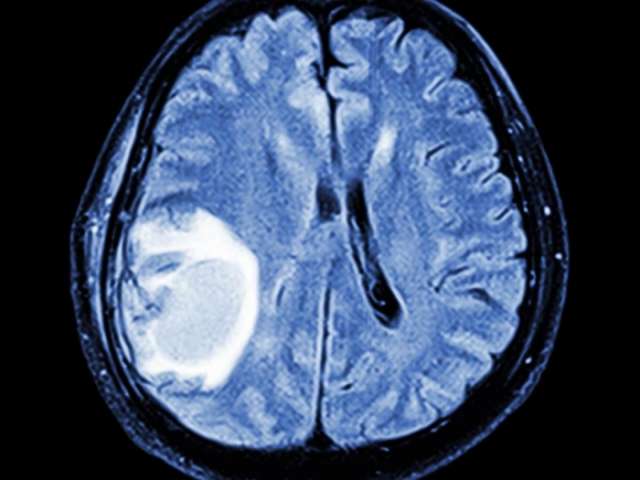

“The presence of cancer in the brain dampens the body’s own immune system,” said Professor Susan Short, an oncologist at the University of Leeds, who led the trial.

However the presence of the virus – which seeks out cancer cells – counteracts this, stimulating the body’s natural defences into action, and is now the subject of a wider clinical trial.

The work adds to a growing body of evidence for the effectiveness of immunotherapy, which is already being employed as a treatment for some cancers.

“Our immune systems aren’t very good at ‘seeing’ cancers – partly because cancer cells look like our body’s own cells, and partly because cancers are good at telling immune cells to turn a blind eye,” said Professor Alan Melcher, a researcher at The Institute of Cancer Research, who co-led the study.

“But the immune system is very good at seeing viruses.”

In this trial, by introducing viruses into brain tumours the scientists were able to essentially “switch on” the immune system’s response to the brain cancer in the nine patients involved in the trial.

As all the patients were due to have their brain tumours removed surgically, they had viruses administered to them days before their operations.

Following the removal of the tumours, the research team was able to analyse them for signs of immune response.

In all nine patients, there was evidence the virus had stimulated an immune response that attacked tumours, even those found deep within the brain.

The researchers found so-called “killer” T-cells attacking the cancer, as well as substances called “interferons” that are known to stimulate an immune reaction.

The presence of the virus itself, on the other hand, caused patients to report nothing more serious than flu-like side effects.

As a control, the scientists used tissue samples from patients who had received surgery but not the virus therapy.

The major breakthrough in this trial was the realisation that the viruses can pass through the “blood-brain barrier” – a membrane that prevents many substances from entering the brain via circulating blood.

Without this capability, the only option would be to directly inject viruses into the brain, a challenging treatment that cannot be administered regularly.

For this trial, the only treatment necessary was a single dose of viruses via an intravenous drip.

The results of this work were published in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

The success of the treatment in this trial has led to an ongoing, larger-scale clinical trial.

“We have begun clinical studies to see just how effective this viral immunotherapy can be at extending and improving the lives of patients with brain tumours, who currently have very limited treatment options available to them,” said Prof Melcher.

The new trial will be the first to administer reovirus, the virus used in the initial study, alongside standard chemotherapy and radiotherapy treatments following surgery to remove tumours.

“Brain cancer is a devastating disease,” said Prof Short.

“For a long time, there have not been many new developments that we could offer patients but the research that is happening at the University of Leeds and elsewhere is beginning to offer a new approach.”

More about: #braincancer