Plato believed hysteria was caused by the mourning womb, which was sad when it wasn’t carrying a child. His contemporaries said it arose when the organ wandered around the body, becoming trapped in different body parts. The latter belief persisted well into the 19th Century, when the disorder was famously treated by bringing women to orgasm with early vibrators.

Even today, the notion that a woman’s biology can befuddle her brain is a staple of popular culture. If a woman is moody, she’s asked if it’s ‘that time of the month’. If she’s feeling sexual, she’s told she might be ovulating.

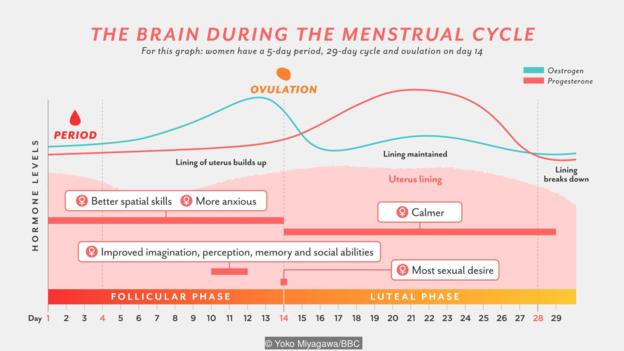

It turns out this isn’t unfounded – some women really do feel more anxious and irritable around their period, and it’s true that we’re more motivated by sex around the time an egg is released. (Of course, that isn’t to say that symptoms can always, or usually, can be explained this way; it’s important to remember that the tendency to attribute women’s complaints to conditions like ‘hysteria’ can have dangerous results.)

Some women do feel more anxious around their period – but other effects of the menstrual cycle are more positive (Credit: Getty Images)

But what’s not widely known is that the menstrual cycle can affect women’s brains in positive ways, too.

It turns out that women are more adept at certain skills, such as spatial awareness, after their period. Three weeks after, they are significantly better communicators – and, oddly, particularly good at telling when others are feeling fearful. Finally, for part of their cycles their brains are actually bigger. What’s going on?

Throughout the menstrual cycle, the brain changes – as does everything from spatial skills to sexual desire (Credit: Yoko Miyagawa/BBC)

Instead of rogue wombs, the main source of these changes is the ovaries, which release oestrogen and progesterone in different quantities throughout the month. The hormones are primarily tasked with thickening the lining of the womb and deciding when to release an egg. They also have profound effects on women’s brains and behaviour.

Scientists have been studying the menstrual cycle since the 1930s. It’s a surprisingly popular research topic, and we now know that it has all kinds of quirky effects, from influencing a woman’s ability to give up smoking to the types of dreams she has each night.

But this mountain of knowledge wasn’t born out of a fascination with female biology. Instead, it was driven by a desire to understand the ways in which men and women are different – and why.

One example of this difference is in our brains. The physical differences between the sexes extend to these wrinkly organs, and scientists have suspected for years that they are down to hormones. “Basically we jump on these natural fluctuations in sex hormone levels that we find,” says Markus Hausmann, a neuroscientist at the University of Durham. “This might be the menstrual cycle in women, or seasonal fluctuations in testosterone levels in men. It’s a full natural experiment.”

Hormones fluctuate seasonally in men and monthly in women (Credit: Getty Images)

One way women are different is that they have superior social skills. Women have better empathy and theory of mind – the understanding that other humans may have a perspective different to our own. They also have better communication skills. This is thought to be part of the reason that male children are four times more likely to be diagnosed with high-functioning autism; girls are better at disguising their symptoms.

“Women speak sooner than men, they’re more verbally fluent than men, and they’re actually better at spelling than men,” says Pauline Maki, a psychologist at the University of Illinois, Chicago.

Women have better verbal skills than men, perhaps an evolutionary result of needing to convey information to their children (Credit: Getty Images)

This social advantage is thought to have evolved because, thousands of years ago, articulate mothers would have been better at conveying vital information to their children – such as not to eat certain poisonous plants.

But are hormones involved? And if so, how much?

Hormonal balance

Back in 2002, together with colleagues from the Gerontology Research Center in Baltimore, Maki set out to learn how fluctuating oestrogen levels affect women’s abilities over the course of each month. Each participant was assessed twice: once just after their period, when oestrogen and progesterone levels were low, and once about a week after they ovulated, when oestrogen and progesterone were high.

It was a small study, involving 16 women who were asked to complete a range of mental tests. But the findings were notable.

During days when the participants had more female hormones in their systems, they were significantly worse at the things men are usually good at (like spatial awareness) and much better at the things women tend to have an edge in (such as the ability to come up with new words). When their hormone levels were lower, their spatial awareness was restored.

After their period, women have improved spatial awareness – a trait men usually tend to be better at (Credit: Getty Images)

One ability that improved when female hormones was higher was ‘implicit remembering’, which Maki describes as the subconscious, effortless kind of memory. “If I said to you, ‘Oh, what was the last Uber fare you had – was it more or less than the Lyft fare?’ And then later on, I asked you, ‘How do you spell fare?’. You might spell it f-a-r-e, even though most people spell it f-a-i-r. Because somewhere your brain encoded ‘fare’ and that was heightened.”

These implicit word memories are important for developing communication skills. They’re the reason we often find ourselves using obscure words or turns of phrase, like “Oh, he was so obstinate”, just after hearing someone else use them, or reading them in an article.

When study participants had more female hormones in their system, they were better at coming up with new words (Credit: Getty Images)

As a result, Maki believes these monthly changes were primarily driven by oestrogen.

The hormone affects two neighbouring brain regions. The first is the seahorse-shaped hippocampus, which is involved in storing memories. Evidence is mounting that the hippocampus is vital to social abilities, since being able to remember your own experiences can help you to understand the motivations of others. The region gets bigger each month when more female hormones are floating around.

The second is the amygdala, which helps us to process emotions, especially fear and the decision to fight or flee. Intriguingly, the amygdala also may be crucial to avoiding social blunders, because understanding why a person is fearful – and deciding if we should be too – requires us to see the world from their perspective. Once you have this ability, you can use it to your advantage in other ways, such as to make moral judgements or even tell lies.

When they have more female hormones in their systems, women tend to be better at seeing a situation from someone else’s perspective (Credit: Getty Images)

As it happens, women’s abilities to recognise fear peak with their oestrogen levels each month. If the hormone is responsible, it also might help explain why women tend to have better social skills overall. The idea is backed up by the fact that women who lack the ability to produce oestrogen aren’t as good at recognising fear and tend to have poor social skills.

Maki believes that most of the effects our menstrual cycles have on our minds are sheer accident. For years, researchers thought that some monthly changes had an evolutionary advantage, such as the widely-reported discoveries that women prefer more masculine, symmetrical men when they’re at their most fertile. But this isn’t actually true – several large-scale studies haven’t found any link.

Brain power

But regardless of why it exists, the monthly transformation of women’s brains could still be an advantage.

The reason lies in another major difference between male and female brains. The latter tend to be less ‘lateralised’ – rather than using just one side of the brain to complete a task, like solve a maths problem, women are more likely to use both.

These left-right divisions are relatively stable. “Most people show a lateralised effect when it comes to the hands,” says Hausmann. “So for example, I’m right-handed. This tells us something about where language is located in my brain. More right-handers have language localised in the left side of the brain than left-handers.” This specialisation is thought to be useful, since most species – from lungfish to lizards – have brains built this way.

Women are more likely to use both sides of their brains, which may lead to more flexibility in thinking (Credit: Getty Images)

Why women’s brains are less so is a big mystery. But this fluctuates, too. Back in 2002, Hausmann discovered that – as with other ‘female’ traits – a woman’s tendency to use both sides becomes more extreme when oestrogen and progesterone levels increase each month. One possible advantage is that these shifts allow for more flexibility in thinking.

“When people have a different pattern in their brains over the course of the month, with them becoming more or less lateralised, this could lead to different strategies of how to solve a particular problem,” says Hausmann. “So people who rely more on the left hemisphere may solve problems in a more logical way, and people who rely more on the right hemisphere maybe rely more on holistic processes when they try to solve a task.”

The next time someone asks if you’re hormonal, you can say yes – but it isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

BBC

More about: women