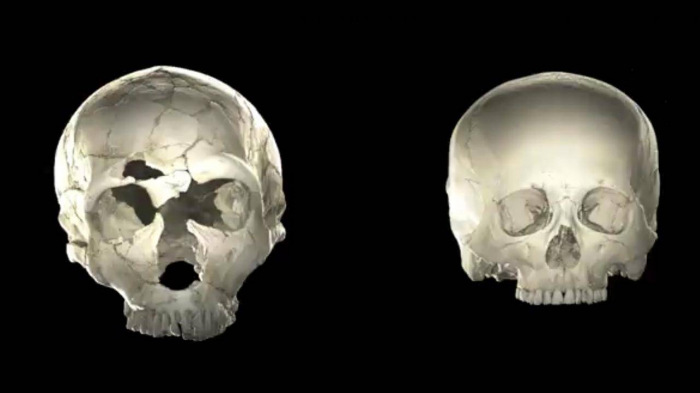

Scientists connected two ancient DNA fragments that have been passed down to select people of European heritage with slight changes in skull and therefore brain shape.

A key feature of the human head is its distinct roundness, in contrast to extinct relatives and ancestors which tended to have longer heads with flatter tops.

Due to some ancient humans breeding with Neanderthals, many Europeans alive today have up to 2 per cent Neanderthal DNA scattered around their genomes.

Previous research has suggested this genetic material may help fight off infections, but the new study is the first to conclude some people still have Neanderthal-like heads.

Professor Simon Fisher, one of the scientists behind the work, said the effects of the DNA fragments were “really subtle”, but they detected them across a large sample size of nearly 4,500 European MRI brain scans.

They then used information from previous Neanderthal DNA studies to identify pieces inside living human genes that were correlated with more elongated heads.

Both fragments contained genes already known to affect brain development known as UBR4 and PHLPP1, which makes sense given the shape of the brain and skull are interlinked.

“We know from other studies that completely disrupting UBR4 or PHLPP1 can have major consequences for brain development,” explained Dr Fisher, a geneticist at the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics.

Both of the brain regions in which the Neanderthal fragments were discovered are involved in key functions such as learning and coordinating movements.

However despite this, the scientists stressed there is no indication the DNA pieces have any effect on the cognitive abilities of modern humans.

“The focus of our study is on understanding the unusual brain shape of modern humans,” said Dr Philipp Gunz, another Max Planck Institute scientist.

“These results cannot be used to make inferences about what Neanderthals could or could not do.”

The researchers said they hope this discovery will help them unravel how modern humans first evolved their distinct brain shape.

They now intend to scale up their studies to include even larger samples, including a sizeable collection of genetic material from British people.

Ultimately they hope to find the full suite of genes controlling the shape of human brains, and understand how their roundness is linked to other characteristics.

The Independent

More about: science