Renaissance artists transformed the course of Western art history by making the nude central to artistic practice. The revival of interest in classical antiquity and a new focus on the role of the image in Christian worship encouraged artists to draw from life, resulting in the development of newly vibrant representations of the human body.

The ability to represent the naked body would become the standard for measuring artistic genius but its portrayal was not without controversy, particularly in religious art. Although many artists argued that athletic, finely proportioned bodies communicated virtue, others feared their potential to incite lust, often with good reason.

The Renaissance Nude at the Royal Academy in London explores the development of the nude across Europe in its religious, classical and secular forms – revealing not only how it reached its dominant position, but also the often surprising attitudes to nudity and sexuality that existed at the time.

Dosso Dossi, Allegory of Fortune, c. 1530 (C redit: The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles)

Nudity had appeared regularly in Christian art throughout the 13th and 14th Centuries. As Jill Burke, co-editor of the exhibition catalogue, says: “The first figure that is nude repeatedly is the figure of Christ.” But from the 14th Century, there was a major shift in people’s attitudes to Christian art and the way it could be used in private devotion and worship. “They were interested in the idea of empathy and using images as a way of really feeling the pain of Christ and the saints,” says Burke.

As a result, artists strove to make images more truthful, with the figure of Christ, the Saints and other religious figures gradually becoming more tangible. This development is evident in the figures of Adam and Eve, painted by Jan van Eyck for his masterful Ghent altarpiece (completed 1432). Thought to be among the first drawn from life, they are astonishingly rich in observed detail. Adam is shown to have sunburned hands while the linea nigra running over Eve’s gently protruding abdomen clearly reveals her to be pregnant.

Jan van Eyck’s Ghent altarpiece (Credit: Alamy)

In their portrayals of the nude, Van Eyck and other northern artists were drawing on a rich, complex native tradition that incorporated not only religious art but also secular themes, including bathing and brothel scenes, produced in media ranging from manuscripts to ivory reliefs. Their development of the rich, lustrous oil painting technique would allow for a far greater level of naturalism.

Naked eye

Northern artists also benefitted from a generally relaxed attitude to nudity. “There’s a lot of nakedness in things like pageants in the North,” says Burke. This was in marked contrast to Italy, where “they had really prescriptive ideas about seeing women’s bodies, even in marriage. The husband shouldn’t see his wife naked for example,” says Burke.

Italians also believed the female body was fundamentally inferior, as according to Aristotle they were not formed properly in the womb, lacking the heat to push out genitalia. Although Italian patrons enthusiastically collected Northern female nudes, perhaps unsurprisingly most 15th-Century Italian artists chose to focus on the male body, although there were notable exceptions such as Botticelli.

Raphael, The Three Graces, c. 1517-18 (Credit: Royal Collection Trust/ Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019)

Drawing on humanist culture and readily available examples of classical statuary, artists began to produce idealised images modelled on the antique. Ghiberti’s panel for the Baptistery doors of Florence cathedral (c 1401-3), which many scholars see as the inception of the Renaissance nude, shows a heroically posed Isaac, the rippling muscles of his chest exquisitely defined in bronze.

Also in Florence, Donatello created an unashamedly sensual sculpture of David (1430-40), his lithe body and languid pose designed for a culture which readily accepted that “men will find the body of a beautiful young man erotic”, explains Burke. Indeed, despite being illegal, same-sex relations appear to have been very much the norm. “More than half of all Florentine men were indicted for having sex with other men in the 15th Century,” says Burke.

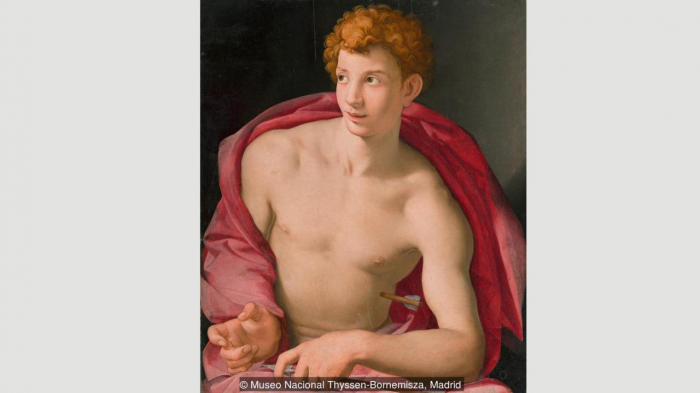

Saint Sebastian was a favourite subject – but it was not only men who were inflamed by his form. An example by Fra Bartolommeo in the Church of Saint Marco in Florence “had to be moved because they thought the female congregation were looking at it too eagerly and having evil thoughts about it”, says Burke.

Agnolo Bronzino, Saint Sebastian, c. 1533 (Credit: Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid)

Despite the unfortunate outcome, there can be no doubting Fra Bartolommeo’s sincere intentions. The same cannot be said for the early 15th-Century illuminated Books of Hours, created for the Duke of Berry by the Limbourg brothers. Ostensibly for private devotion, they included images of figures such as Saint Catherine with a pinched-in waist, high-set breasts and delicate pale flesh, which bordered on the erotic.

Jean Fouquet painted the king’s mistress, Agnès Sorel, as the Virgin Mary, her perfectly circular left breast bared to a distinctly uninterested Christ child

Works such as this set the stage for the ongoing fusion of the spiritual with the sensual in religious art in France. Jean Fouquet’s arrival at the court of Charles VII only heightened this propensity. His portrayal of the king’s mistress, Agnès Sorel, as the Virgin Mary (1452-55), her perfectly circular left breast bared to a distinctly uninterested Christ child, was one of the most bizarre examples.

Madonna surrounded by Seraphim and Cherubim, by Jean Fouquet, 1452 (Credit: Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp, Belgium)

These developments did not go unnoticed by the Church and, after the Reformation of 1517, religious imagery was banned from places of worship. Artists in Protestant nations responded by turning to secular and mythological themes of nudity, with Lucas Cranach the Elder producing some 76 depictions of Venus. It gave artists the “option to explore these themes outside of the religious sphere which allowed for a huge amount of freedom”, says the Royal Academy’s Assistant Curator, Lucy Chiswell.

The portrayal of nude woman as witches also became popular. In highlighting their supposed sexual power over men and the need for this to be controlled, it fed into the growing witch craze that saw thousands of women executed. “It’s not making the nude grotesque in any way, but it’s associating them with these demonic, very strong controlled figures,” says Chiswell.

Titian, Venus Rising from the Sea, c. 1520 (Credit: National Galleries of Scotland)

Italy, too, was increasingly adapting classical themes spurred by the expanding interest in humanist literature and poetry. The Venetian artists Giorgione and Titian produced gloriously voluptuous nudes. But despite their evident eroticism, these paintings were often based on descriptions of classical nudes, allowing their owners to claim their interest was intellectual rather than sexual.

In any case, as Burke points out, “one of the testaments of the skill of the artist is to produce a bodily reaction in the viewer – so if you felt erotically aroused by, say, Titian’s Venus of Urbino that was a testament to the skill of Titian.”

Having purely classical nudes was one thing but the influence of the antique in Catholic religious art was becoming increasingly contentious. Michelangelo, along with the Christian humanists and clerics within his circle, believed a beautiful body to be the emblem of human virtue and perfection. But his attempts to reinvigorate Christian art by embracing ancient pagan models in his depictions of Biblical figures for the Sistine Chapel, particularly in The Last Judgement (1536-41), proved too much for the Church. After his death, the genitalia of the figures were covered in drapery.

After Michelangelo’s death, the figures he painted in the Sistine Chapel were covered in drapery (Credit: Alamy)

But despite the Church’s prudery, Michelangelo’s genius was instrumental in the nude coming to be seen as the highest form of artistic expression. After the Sistine Chapel, “everyone wanted their artists to paint nudes”, says Burke.

Over time, the nude may have become predominantly female: but for two centuries, the beauty of both sexes was celebrated by some of the greatest artists who have ever lived.

BBC

More about: Renaissance