The sun beats down, chickens scurry about and music sounds from under the tarp of a makeshift kitchen. The morning clouds part, giving way to the sight of the partly snow-covered, active Popocatepetl volcano in the distance. Along the streets of Hueyapan, Morelos, debris still lies scattered from the deadly 7.1 magnitude earthquake of September 2017. The quake’s epicentre lies just 60km south of here.

Resident Pablo Cuauhtémoc Saavedra Castellanas stands next to the beginnings of what will be his family’s new home. But unlike many of his neighbours, Saavedra is not using concrete blocks to rebuild. The material he’s using is called superadobe. As an earth-based material, it doesn’t require outside resources. And, perhaps most excitingly for locals in this seismically active area, it is earthquake resistant.

Polypropylene bags filled with a mixture of earth and lime are stacked on top of each other. The walls of the house are caked with three layers of dirt, lime, ground grasses and horse manure. Saavedra’s roof is currently a tarp; later, the tarp will be replaced with locally made clay tiles that have been part of the regional architecture for centuries.

The superadobe home of Pablo Cuauhtémoc Saavedra Castellanas is shown under construction (Credit: Mallika Vora)

“For me, it’s fascinating to have a superadobe home, above all because of the architecture and the use of earth, using local resources,” Saavedra says. “I’m passionate about our culture and traditions. We have built homes out of earth for many years. Having a house made of superadobe is like taking it to another level.”

Saavedra is a young weaver following the tradition of his grandmothers, creating textiles made with sheep’s wool and dyed with local plants. He also teaches Nahuatl, the most widely spoken indigenous language in central Mexico.

During the earthquake, both his home and the Nahuatl school crumbled, along with about 300 other documented cases of damage in this mountainside community of around 7,500 people. Some 10 people died. Many others were injured.

Saavedra and his family are the beneficiaries of materials and instruction from the Mexico City-based architecture group Siembra Arquitectura, which aims to provide people made homeless by the earthquake with the knowledge they need to build structurally sound buildings.

One material they’re encouraging is superadobe.

Superadobe is made from earthen material fortified with lime, then compressed into bags piled on top of each other (Credit: Getty)

Superadobe was designed by Iranianian-American architect Nader Khalili. He first proposed earthbag construction at a 1984 Nasa symposium that tasked participants to share ideas of how to build on the Moon and Mars, using material available onsite, as the costs of taking materials from Earth into space would be exorbitant.

Earth really is gold: 99% of the material that you need to build a shelter for yourself is on your own land - Sheefteh Khalili

“When my dad gave that presentation, his case was that earth really is gold: 99% of the material that you need to build a shelter for yourself is on your own land. Talk about true sustainability and empowerment,” says Sheefteh Khalili, co-director of Cal-Earth Institute. A nonprofit that her late father founded in 1991, the institute teaches people how to build disaster-resistant, sustainable structures using earth-based architecture.

Superadobe isn’t unlike adobe, which has been used in this region for centuries. Adobe is an earth-based material consisting of soil compacted with organic materials such as corn stalks, hay, and animal manure. It is one of the oldest building materials in the world, though its exact components can vary.

The interior of a superadobe home at the Cal-Earth Institute (Credit: Getty)

Superadobe is also manufactured from earth and organic materials. But the mixture is fortified with lime, then compressed into polypropylene bags (the same material used to create sandbag levees) which are piled on top of each other, each heavy layer separated by barbed wire. This holds the bags in place and effectively forms the walls of the structure.

Superadobe homes are estimated to last for centuries and are cost-effective to produce. In this remote farming community, the making of the new material also carries the potential of creating autonomy and better-paid jobs.

“My father designed superadobe to be built pretty much everywhere,” Sheefteh says. “We haven’t found a context that it’s not an option in.”

Nader Khalili’s superadobe was inspired by ancient dwellings in harsh climates such as the deserts of the Middle East. Superadobe structures have been shown to withstand devastating devastating natural disasters. After both the 7.2 magnitude earthquake in Nepal in 2015 and Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico, superadobe buildings were still standing.

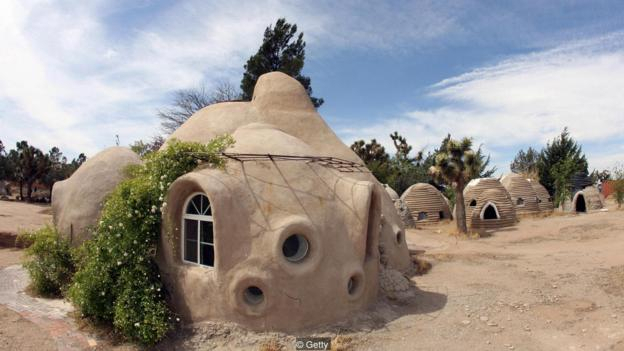

Superadobe houses at the Cal-Earth Institute, a nonprofit founded by Nader Khalili to share the technique with others (Credit: Getty)

There are now countless superadobe homes around the globe, ranging from emergency shelters to luxury homes. Superadobe has been used for everything from structures built by Oxfam International at Jordan’s Za’atari refugee camp to a building at southern California’s educational nonprofit the Ojai Foundation – one which survived the deadly Thomas Fire of December 2017 to January 2018.

Many of them are dome-shaped, which is considered more resistant to the elements because of the physics behind arch construction. But in Hueyapan, locals wanted a more traditional-looking home than a domed design. So Siembra Arquitectura designed rectangular homes – but ones enforced with buttresses on every angle.

Locals wanted traditional-looking homes in Hueyapan, so Siembra Arquitectura designed rectangular suberadobe buildings (Credit: Mallika Vora)

Sheefteh Khalili says Cal-Earth’s dream would be to have the ability to deploy trained builders in emergencies, to disaster zones and refugee camps for example, bringing with them just a duffle bag full of key materials and relying on the earth and other natural resources in the region to complete the recipe.

“Understanding the principles of building with superadobe means understanding that it’s rooted in ancient and indigenous architecture, but that we can today raise buildings that work in harmony with nature and are sustainable, modern and really safe,” Sheefteh says. “People can live their lives in these houses that will be there for generations to come.”

Superadobe and adobe both have benefits for extreme climates – as in Hueyapan, which at a 2,500m altitude can experience near-freezing temperatures at night and blazing sunshine during the day. Adobe is a thermic material that captures the heat of the day, releasing it into structures during the night. Overnight it does the opposite, absorbing coolness which will be felt during the daytime.

For locals, one problem with the material can be the time it requires. It can take up to three months to build a superadobe home, depending on the weather. Adobe and superadobe production both involve mixing materials and then stepping on them – with the help of horses, in Hueyapan’s case – in order to fully compact the mixture. Central Mexico’s lengthy rainy season can slow down the process further.

This is one of the reasons some people who lost their homes would rather have a new house built out of concrete blocks: it’s faster.

Juan Manuel Espinoza Cortés was one of the first recipients of a superadobe home in Hueyapan, of which there are now at least eight. He shares the three-bedroom home that sits in front of his abundant, wild orchard with his parents Don Luz and Doña Célia. He learned the entire process from the ground up from Siembra Arquitectura and now is the foreman on all of its projects in Hueyapan.

As a thermic material, adobe releases heat into homes at night and coolness during the day (Credit: Mallika Vora)

“Building with concrete is easier,” Espinoza says. “We have to step on the adobe. We use horses, we use humans. When you begin to step on it, to make a level ground, you realize how intensive a process it’s going to be. But now that we understand how to do it, we are moving faster. We are enthusiastic about it.”

Mexico’s two major earthquakes in 2017 weren’t an anomaly, and Espinoza has witnessed his new home react to a few since. “It sways with the movement of the earth,” he says. “I watched it move and settle. And others have seen that as well; that gives people faith. It proves that it’s a quality material.”

Now, about three months after they began, Saavedra’s superadobe home is nearly finished. His family has moved in. While laborious, he says, the process was not difficult to learn. And he is happy with it.

“It’s truly an ecological construction,” he says. “The rectangular design more than anything is pleasant because it’s really a home – and it has everything necessary for the wellbeing of the family.”

Read the original article on BBC.

More about: superadobe