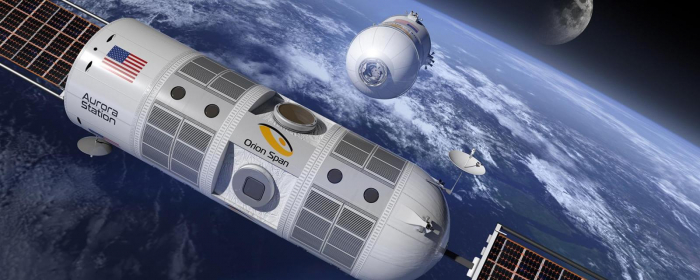

It was intended to set the travel world on fire: Aurora Station, the world’s first in-orbit hotel. The official announcement took place last April during the Space 2.0 Conference in San Jose, California. Housed aboard a structure about the size of a large private jet, guests would soar 200 miles above the Earth’s surface, enjoying epic views of the planet and the northern and southern lights.

A jaunt won’t be cheap: the 12-day-journey aboard Aurora Station, scheduled to be in orbit by 2022, starts at a cool $9.5m (£7.3m) per person. Nevertheless, the company says the waiting list is booked nearly seven months ahead.

“Part of our experience is to give people the taste of the life of a professional astronaut,” says Frank Bunger, founder and chief executive officer of Orion Span, the firm which is behind Aurora Station. “But we expect most guests will be looking out the window, calling everyone they know, and should guests get bored, we have what we call the ‘holodeck,’ a virtual reality experience. In it you can do anything you want; you can float in space, you can walk on the Moon, you can play golf.”

Think of Aurora Station, which concluded a crowdfunding campaign in early February, as “astronaut-lite”, a luxurious descendant of the austere International Space Station (ISS). There will be some similarities: in both, visitors (four guests with two staff) will nap in sleeping bags attached to the superstructure, the food will be freeze-dried, and all guests will have to go through a vigorous pre-launch health screening. The journey to Aurora alone means being subjected to 3Gs of gravitational force.

Aside from gazing out at the stars and back at Earth, it is expected that Aurora visitors will spend some of their stay tending micro-gravity experiments such as growing food, as is currently done by crews on the ISS. But there will also be some differences: water will be imported with each round of guests, rather than being processed from their own urine.

Many in the science community see this as the inevitable next great leap for mankind. But there is that age-old adage of looking before you leap; to say that civilian space travel is in its embryonic stage is almost overstating how advanced it is. Even as the media gushed over Aurora, the experts were far more cautious.

“I mean, Aurora Station is a nice gadget,” says Christian Laesser of the Research Center for Tourism and Transport at the University of St Gallen in Switzerland. “But if it will be implemented remains to be seen.”

What is still to be determined are the safety and engineering standards for a civilian space vehicle

“At the moment space tourism is a field where reality, hoaxes, and science fiction are mixed up in such a way that it makes difficult to distinguish between reality and wishes,” adds Robert A Goehlich of Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, who gives the only class in the world dedicated to space tourism.

Both agree that space tourism is already a thing; it began in 2001 when American Dennis Tito paid the Russian Space Agency a reported $20m for a seven-day visit to the ISS. Some countries are already laying the groundwork for the future of the industry; 10 commercial spaceports are already taking shape across United States, for instance. Eric Stallmer, president of the Commercial Spaceflight Federation and arguably Aurora Station’s biggest cheerleader, points out the USA has regulations on the books in the form of the Commercial Space Launch Competitive Act, passed in 2016, that addresses issues such as liability, indemnification, responsible parties, and risk.

A few moneyed tourists have been able to pay to visit the International Space Station (Credit: Getty Images)

Likewise, neither Goehlich and Laesser are naysayers, but both take a wait-and-see approach to whether civilian space tourism firms can deliver, and how. What is still to be determined are the safety and engineering standards for a civilian space vehicle. Bunger describes Aurora Station, with its newer technology, simplified systems, and smaller area (thus avoiding more micrometeor collisions), as safer than the ISS, but even he admits it won’t be insured until the moment it lifts off.

But that raises an even bigger unaddressed questions – where will Aurora Station be launched from and where will guests be retrieved from once they return to Earth’s surface.

Moreover, this is an industry where setting dates is a recipe for disappointment. Virgin Galactic, which had its first successful to-space-and-back test flight in December, is still nine years behind schedule, SpaceX and Blue Origin are still testing their vehicles, and XCOR Aerospace declared bankruptcy in 2017. There is a very real possibility that older candidates on the various waiting lists may “age out” of the running, or develop health conditions that exclude them. The Aurora Station module itself is not even set to be constructed until later this year.

Then there are the health issues. In the case of Aurora Station, people suffering from claustrophobia, even slightly, should think twice about a booking a room in a property 43.5ft long by 14.1ft in diameter (it’s not like you can open a window). Because objects, including the fluids in the body, tend to rise in low gravity, guests should prepare for some unflatteringly moonfaced selfies, with the added bonus of nausea as the stomach adjusts to weightlessness.

Long-term exposure to zero-g weakens the bones and changes the structure of the eyeball radically enough to affect sight; being just 12 days in antigravity means guests will not have to worry, although staff definitely will. Happily, microgravity does not adversely affect menstruation (although issues with storage of sanitary items and limited washing water may prompt female astronauts to go on the pill). Because of the kinetics involved, Nasa requires astronauts to abstain from sex, which may take some of the romance out of such a trip.

Private companies like SpaceX are still testing their vehicles and not yet sending people into space (Credit: Getty Images)

More alarming are the charged particles entering the cabin that could potentially cause genetic damage; as insulated as space vehicles are, they are not fully proofed against such cosmic radiation. Astronauts in the past have reported seeing flashes of light, which researchers surmise are cosmic rays hitting the optic nerves or visual cortex in the brain.

“You cannot execute a space mission, in particular a commercial manned one, ‘a little bit’ or on a ‘let’s try and see if it works’ basis,” Goehlich warns. “You need safe operation of the spaceships, an environmentally friendly operation, and ultimately an economically profitable operation.”

But Laesser sees space tourism as a natural progression, noting that extreme environments have only slowed, but not impeded, exploration. He states, “If you go back 30 years ago, Antarctica was impossible, and now people are going to Antarctica. We have these new frontiers, space is just the latest one which might be open.”

Exactly when it will open, however, no-one is quite sure.

BBC

More about: Space