“As Arabs we have to make sure we have three things when we pack: our passports, a bunch of cash, and a handheld portable bidet,” joked Egyptian comedian Bassem Youssef during his debut UK performance in June. He waved around a portable spray hose, also known as a shattaf or “bum gun”, as a prop. “I don’t get it: you guys are one of the most advanced countries in the world. But when it comes to the behind, you’re behind.”

Plenty of people would agree with Youssef. The penchant in many Western countries for wiping after using the toilet – rather than rinsing off – is a source of puzzlement around the world. Water cleans more neatly than paper: at the risk of inspiring an “ew!”, imagine trying to remove chocolate pudding from your skin with tissue alone. Plus, while toilet tissue may not be as harsh as pieces of ceramic (used by ancient Greeks) or corn cobs (used by colonial Americans), we can all agree that water is less abrasive than even the softest five-ply.

Residents of many nations have long been ending a toilet visit with water. And that isn’t just true of the non-Western world. The French of course gave the world the word bidet, and even though the devices are fading away from France, they remain standard in Italy, Argentina, and many other places. Meanwhile, Youssef’s beloved “bum gun” is commonly found in Finland.

Still, much of the West relies on toilet tissue – including the UK and US. And compared to anywhere else in the world, these two nations have had the greatest influence on modern bathroom culture, notes architectural historian Barbara Penner in her book Bathroom. In fact, Anglo-American bathroom trends became so widespread that, in the 1920s, they were even dubbed “sanitary imperialism”.

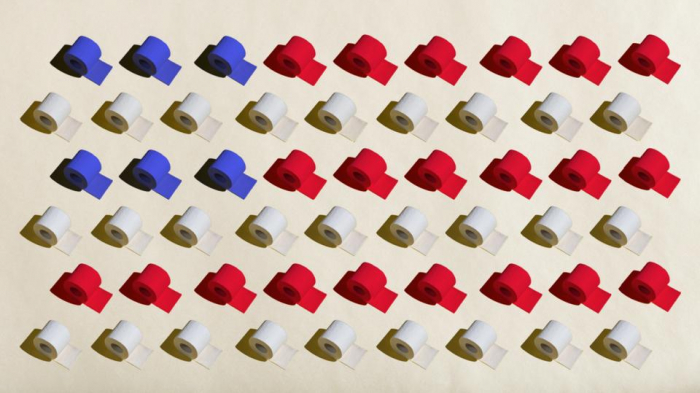

Anglo-American bathroom trends are so widespread, in the 1920s they were dubbed ‘sanitary imperialism’ (Credit: BBC/Getty Images)

Even so, those trends didn’t penetrate everywhere. Water is preferred, for example, in a number of majority-Muslim countries, as Islamic teachings include the use of water for cleaning. (Turkey’s Directorate of Religious Affairs did however issue a fatwa in 2015 specifying that Muslims can use toilet paper if water isn’t available.) And the famously whiz-bang modern Japanese toilets, which simultaneously reflect technological ingenuity and shame about bodily functions, offer both wetting and drying options.

One person who’s been interested in the water-or-paper debate is Zul Othman, a project officer for the Australian government who has researched cultural and historical attitudes towards toilet facilities. As Othman’s research shows, some Muslim Australians have adapted to Western-style bathrooms by using both toilet paper and then showering, filling a jug of water, or installing handheld bidets next to their toilets.

This is the case for people of non-Islamic religious backgrounds too. Astha Garg, a data scientist from Navi, Mumbai who has been working in the San Francisco Bay area for the last two years, says she looked high and low for a bath mug for her toilet. (To the uninitiated, this resembles a plastic measuring jug used for baking, with a handle and a spout for pouring water onto one’s nether regions.) Eventually she had to go to an Indian-owned store.

“Some Indians do adapt to toilet paper, but a lot of us like to stick to water whenever possible,” she comments. “Whenever visiting an Indian friend in the US, I can almost always count on them having a plastic water bottle or a mug beside the toilet.”

It may have been the French who gave the world the word bidet, but water is also preferred in many majority-Muslim countries, among other places (Credit: BBC/Alamy/Getty)

Othman has witnessed the stubborn Western insistence on using some form of paper. One of his classmates in Sheffield, UK ran out of toilet paper and ended up using a £20 note to wipe.

Meanwhile, the family of podcaster and metal guitarist Kaiser Kuo have adopted a hybrid solution. Three years ago they moved from Beijing to the US – where, like many new arrivals, they retained some Chinese habits and picked up some American ones. Kuo was shocked at how much loo roll his kids started going through in keeping with Americans’ status as, by far, the world’s foremost consumers of toilet paper.

Garg found toilet paper baffling as well. “It was not at all obvious that it was to be thrown in the toilet bowl,” she says. In addition to the financial and environmental costs, “it chokes toilets. It seems to me that every one in four toilets has plumbing issues”.

Americans are, by far, the world’s foremost consumers of toilet paper (Credit: BBC/Alamy)

Toilet paper also is commonly used in China, where, after all, paper was invented. But US manufacturers and advertisers were the ones who aggressively pushed toilet paper use in the 20th Century, especially certain kinds. For instance, Brits were still mostly using hard toilet paper in the 1970s, as they distrusted the soft paper being purveyed by Americans.

Kuo’s family now use less toilet roll, followed by flushable wet wipes. It’s a kind of American acknowledgement of what people in other countries have known for centuries: that moisture cleans better.

Sit or squat?

Kuo’s family have also compromised on that fascinatingly divisive topic: sitting vs squatting. Both types of toilets were used during the Han Dynasty (206BC–220AD), and there have been regional differences within China in this preference, although the squatting variety now predominates in public toilets nationwide.

Even today, it’s estimated that two-thirds of the world squats. Yet many Westerners remain resistant to a model that’s arguably more logical and more convenient than the porcelain throne. Consider that a majority of British women have admitted to crouching or hovering in public toilets in order to avoid direct contact with the seats. The squat toilet neatly avoids excessive bum-to-seat intimacy.

Anatomically, squatting is the better posture too, as the angle allows for smoother passage. Bowel movements are faster and less straining is involved. This doesn’t even get into the many health benefits of squatting in general – a practice (and display) of strength and flexibility where elderly Chinese generally put young white folks to shame.

Americans have turned this longer toilet time into a form of leisure. There’s a large market for books to read while sitting on the toilet, which generally involves trivia, short stories or jokes. That still strikes Kuo as odd. “What all Chinese parents will tell you is: don’t read on the toilet. You’ll get haemorrhoids.”

Sitting instead of squatting can make for longer toilet time – which Americans have turned into a form of leisure (Credit: BBC/Alamy/Getty)

Kuo’s family has come up with a halfway solution for their Chinese American household. “We keep a little footstool in front of the toilet, so when you’re doing your business, putting your feet up on that stool sort of emulates the squatting position,” he says, laughing. “I think my wife’s a genius for having discovered that.” Several companies have rushed to monetise this kind of compromise, with devices like Squatty Potty tailored to Western markets. Garg owns one.

Another kind of compromise is giving people an option. Facilities in certain countries provide both seated and squat toilets. As Othman says of his home country of Malaysia, “In retail and shopping areas, they normally will allocate 1/3 or the available public toilets as squatting toilets.” His research suggests that Muslim Australians are comfortable with switching from squat to seated toilets – but that they retain a preference for water over toilet paper.

Weird washing

Bathing also varies culturally. “There is a tendency to expect early showering in Western societies, or getting wet every day, and that’s weird,” reflects Elizabeth Shove, a sociologist at the University of Lancaster who researches water and energy consumption practices.

One key influence was the global advertising boom that accelerated after the world wars: products included Lifebuoy carbolic soap in Zimbabwe and Ivory soap in the US. Even soap operas got their name from the heavy advertising, on radio and then television, by American soap manufacturers.

Using special kinds of soap on the body and face, rather than catch-all cleaning products that could also work on clothing, remains a fairly recent invention

Today, the idea of using special kinds of soap on the body and face, rather than catch-all cleaning products that could also work on clothing, remains a fairly recent invention partly attributable to marketing. This manufactured need was linked to a general trend toward more frequent bathing.

Another relatively recent, and now nearly ubiquitous, concept in the West is the normalcy of the daily shower. Shove notes that just two generations ago, it was standard in the UK for people to bathe once a week. Of course, in many places around the globe today – as in the UK in decades past – water supplies are unreliable, and many people don’t have a choice about the frequency of bathing.

Whether you wash in the morning or evening may have more to do with your cultural practice – and with marketing – than hygiene (Credit: BBC/Getty)

But the availability of water isn’t the only factor affecting this. Frequent bathing is common even, for instance, in low-income parts of Lilongwe, Malawi, whose residents might take bucket-based baths two or three times a day despite intermittent water access.

Many Ghanaians, Filipinos, Colombians and Australians, among others, also bathe multiple times a day. This may not include washing the hair each time, and there might be supplementary foot washing in cultures where this is important. Multiple bucket baths might actually use up less water overall than a single high-pressure shower. But the habit is only partly related to a hot climate: some Brazilians take multiple showers even on winter days.

Today’s typical routine of a morning shower is partly a reflection of contemporary notions about how to structure the day, which is more rigorously ordered than in the past. (Today’s Westerners feel they have less free time than ever before, even though working hours are shorter, partly because so much of their time is scheduled.)

There’s also a stronger sense now of showering as a way of making yourself presentable to others, rather than washing away the day’s grime. It reflects the change in the types of labour done, too: fewer Westerners are now involved in the kinds of manual or agricultural work that would call for rinsing off dirt.

Scheduling sensibilities aside, is it more hygienic – or helpful – to shower daily, and to do so in the morning or the evening? Not always. Frequent hot showering can dry out the skin and hair (leading to the trend of women washing their hair just once or twice a week). Evidence also is mixed about the benefits of a morning or evening shower. Some swear by the alertness brought about by a morning jolt of water, but an evening bath, as is common in Japan, can help with relaxation of muscles before bed.

An evening bath, as is common in Japan, can help you relax before bed (Credit: BBC/Alamy/Getty)

Of course, there’s a huge amount of variation within any country, so there are exceptions to all of these trends. And the history of hygiene habits suggests that none of these is permanently locked in place – it all could change alongside cultural and technological developments.

In the future, perhaps, people in the West might signal their eco-virtue by announcing that they shower only once a week, or have traded in their power showers for the bucket-and-cup method. Or some might also choose to install bidet hoses next to their toilets after seeing how useful people from other countries find them.

Bathroom habits may seem to be a matter of common sense, but they’re the result of a great deal of social conditioning. After all, everyone has to be taught how to use a sauna, a bidet, a shower or even – as parents potty training an infant are keenly aware – a toilet.

Weird West

This article is part of our Weird West series. Back in 2010, a team at the University of British Columbia pointed out that psychology research contains a major flaw: much of it is based on samples entirely from Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich and Democratic – or Weird – societies. The researchers often assumed that their findings would be applicable to people anywhere. But when they did a review, the university team found that from reasoning styles to visual perception, members of Weird societies are, in fact, “among the least representative populations one could find for generalising about humans”.

From the mainstream media to academia, however, it remains common to see the Weird as “normal” – or at least as a “standard” against which other cultures, and people, are judged. In this series, we dig into what this looks like in everyday life. What habits and ways of thinking are common in Weird societies that people living elsewhere in the world might find, well, weird? And what does this tell us, not only about cultural differences, but about ourselves? From when we shower to how we shop, this series re-examines the behaviours often taken for granted – and explores how the “standard” is rarely the best, or only, way.

BBC Future

More about: bathroom