When King Tutankhamun’s tomb was opened in November 1922, the world fell under his spell. For today’s archaeologists, the explanation for the cult of King Tut lies in the exceptional richness of the discovery, especially as many of the tombs were robbed of their mortuary goods; and in the mystique surrounding the premature deaths of the boy king and Lord Carnarvon, who funded the dig. As the largest collection of Tutankhamun’s treasures to travel outside of Egypt goes on display at the Saatchi Gallery in London (after drawing record-breaking numbers in LA and Paris), the find clearly still has a global appeal in the 21st Century.

But as I explore in a new Radio 4 programme, The Cult of King Tut, the power of King Tutankhamun lay as much in the extraordinary context of the 1920s as it did in the contents of the tomb. In 1922, Howard Carter, the British archaeologist who found the tomb, was caught in the middle of a political storm. Egypt had recently undergone a political transformation, and the new government kept a tight control on the artefacts.

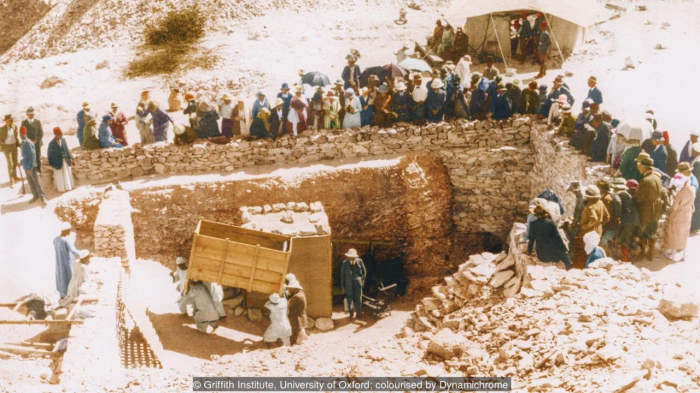

1923, Thebes: tourists crowd around the entrance to the tomb to watch a large object being removed from Tutankhamun's tomb, on its way to the workroom (Credit: Griffith Institute, University of Oxford; colourised by Dynamichrome)

To raise money to pay for the complex process of excavation, preservation and cataloguing the tomb’s riches, Lord Carnarvon signed an exclusive deal with The Times newspaper giving it sole rights to supply the world’s press with news and photographs. At the time, this sort of arrangement was extremely unusual. Cat Warsi, assistant archivist at the Griffith Institute in Oxford, argues the financial support and continued media interest was vital “because this was a costly excavation that in the end took almost 10 years”.

Lights, camera, action

Harry Burton, a British-born art photographer at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, was brought in to photograph the excavations. His approach was meticulous and dramatic, photographing objects from multiple angles with specialist lighting and staging that were being developed in the new film industry in Hollywood at the time.

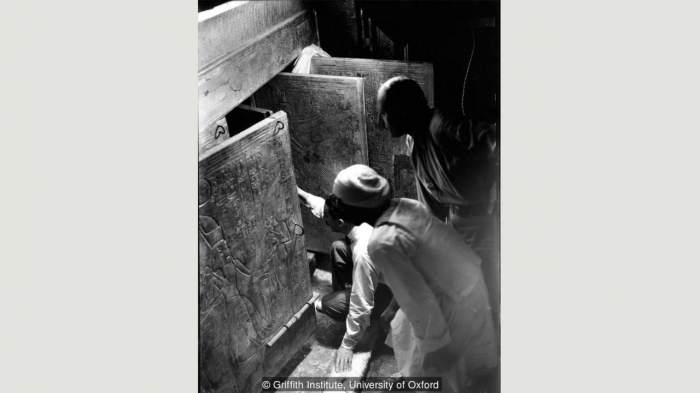

Burton staged his photos to make them as dramatic as possible; taken in February 1923, this image is one of only two showing Carter (left) and Lord Carnarvon together in the tomb (Credit: Griffith Institute, University of Oxford)

The dig revealed that the world was enchanted by the treasures – extraordinary and ordinary. Paul Collins, curator for the Ancient Near East at the Ashmolean museum in Oxford, says this ‘Egyptomania’ was fed “by a perfect storm of technology. The moment when radio, telegram, mass-circulation newspapers and moving film came together so everyone could have a bit of Tut”.

The excavation by Carter (here, kneeling in the burial chamber) was one of the most important archaeological finds of the 20th Century; many of the objects have yet to be studied (Credit: Griffith Institute, University of Oxford)

Burton’s photographs revealed more than 5,000 objects crammed into the small tomb. Among the exquisite golden statues and jewellery, decorated boxes and boats, and dismantled chariots, there were also signs of everyday life: loaves of bread, haunches of meat, and baskets of chickpeas, lentils, and dates. There were even garlands of flowers.

Harry Burton documented the contents of Tutankhamun’s tomb – including this white box, which contained linen shirts, shawls and loin cloths, 18 sticks, 69 arrows and a trumpet (Credit: Griffith Institute, University of Oxford; colourised by Dynamichrome)

The discoveries inspired fashion design of the 1920s, as generic Egyptian motifs of snakes, birds and lotus flowers appeared on exclusive clothing designs, as well as mass-produced consumer goods available to everyone. Burton’s pictures of luxury items spoke to the new consumerism of the 1920s. The US economist Thorstein Veblen had recently coined the phrase ‘conspicuous consumption’, which summed up the ‘Roaring Twenties’ consumer economy, and what Veblen called the ‘display power’ of shopping; ostentatious consumption showed to the world you could afford to buy more than life’s bare necessities.

King Tut fed people’s fantasies, and the demand for products that referenced his world. It was perhaps easier to relate to it than some other ancient kingdoms because Tut’s father, Akhenaten, had ushered in a new style – Amarna art – that represented royalty in softer, more natural settings, offering intimate representations of family life. And women were much more prominent.

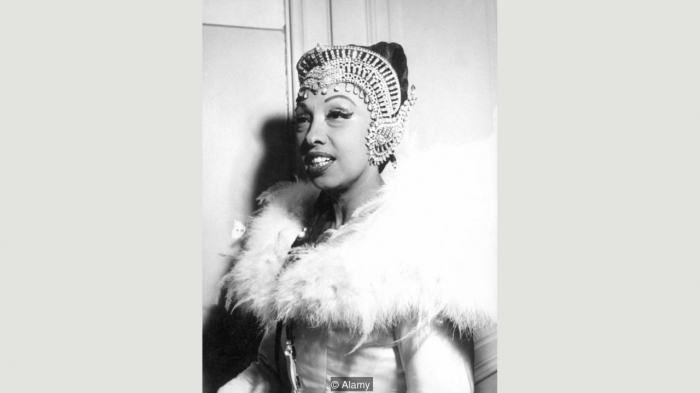

Figures such as the goddess Isis, one of four statues guarding each corner of King Tutankhamun’s canopic shrine, were inspirational for ‘modern girls’, a new kind of woman who was emerging after World War One.

Depictions of the goddess Isis, such as on this ornamental breastplate found in the tomb, were modern-looking, her bobbed hair and shift dress chiming with the 1920s modern girl (Credit: Alamy)

The ‘modern girl’ was a global phenomenon – neue Frauen in Germany; modan gāru or moga in Japan; modeng xiaojie in China; garçonnes in France. They shared a common style that stood for liberation. With a Cleopatra-style bob haircut and shift dress, sipping cocktails and dancing the rhythm of a jazz band, the modern girl signalled defiance. She could attract a man or get by without one.

She was also a commodity icon – selling lipstick, face powders, perfumes, and face creams. Many of them, like Nile Queen products manufactured by the Kashmir Chemical Company in Chicago, were marketed with an explicit Egyptian theme.

Jazz Cleopatra

The modern girl was epitomised in the African-American dancer Josephine Baker, who styled herself as a ‘Jazz Cleopatra’. A prominent user of beauty products for black women produced by Madam CJ Walker, one of the most influential and well-known black US businesswomen, Baker used this new beauty culture to empower herself. She challenged racism by being fashionably modern.

Josephine Baker was known as the ‘jazz Cleopatra’ (Credit: Alamy)

Baker became famous for her jazz routines at the Folies Bergère in Paris, popularising the Charleston, the dance craze from the US. As dancers were no longer necessarily paired ‘in hold’ (dancing in one another’s arms with the man leading), it looked revolutionary. According to the Paris-based musicologist Martin Guerpin: “Once you dance alone, you can do whatever you want.”

King Tut also inspired jazz music, including the 1923 tune Old King Tut, which declared he was a ‘wise old nut’. The recognition that he was a boy king emerged a few years after the tomb’s discovery: Carter’s excavations only reached Tutankhamun’s body in 1925, when he opened the first of a series of coffins that revealed the king’s gold funerary mask, and sometime later, his fragile, broken body.

29-30 October 1925: Carter and an Egyptian workman examine the third (innermost) coffin made of solid gold, inside the case of the second coffin (Credit: Griffith Institute, University of Oxford; colourised by Dynamichrome)

A painstaking autopsy revealed that King Tut was not a vulnerable old king, but a young man, aged between 17 and 19. The discovery that the ‘boy king’ had suffered multiple injuries fuelled a new bout of fevered speculation and curse stories that linked back to the death of Lord Carnarvon, only weeks after the tomb’s opening.

The discovery that Tutankhamun was a boy king, and that his body carried multiple injuries, captured the imagination of people mourning their war dead

The cult of King Tut also had a dark side that spoke to people’s private fears and hidden suffering. His body was unearthed at a time when society was still recovering from the impact of World War One. Most of the war casualties were also entombed far from home, their bodies never returned. The discovery that Tutankhamun was a boy king and that his body carried multiple injuries, after his mummy was unwrapped in 1925, captured the imagination of people mourning their war dead – or nursing injured loved ones.

The bandaged, wounded young men who made it home from the front returned with some of the worst injuries ever seen, and were treated out of sight because weak male bodies represented weak empires. Mummies who could rise from the dead were now immortalised by the new film industry. According to Roger Luckhurst at Birkbeck College: “The first journalist to see the face of the pharaoh Tutankhamun was John Balderston, who went on to write the script for the Universal horror film The Mummy [released in 1932].”

Luckhurst believes Burton’s photos of the treasures and their discovery help cast Carter and Carnarvon as “heroic figures with derring-do”, becoming the templates for heroes like those in Raiders of the Lost Ark and Lara Croft: Tomb Raider.

The 1920s craze for King Tut was a global project of the imagination. It connected people to an ancient place and to one another, including loved ones whose loss was mourned – allowing them to imagine themselves in a different, and possibly better, world. And the need to dream of new worlds, by recovering ones lost to history, is as important as ever.

BBC Future

More about: Tutankhamon