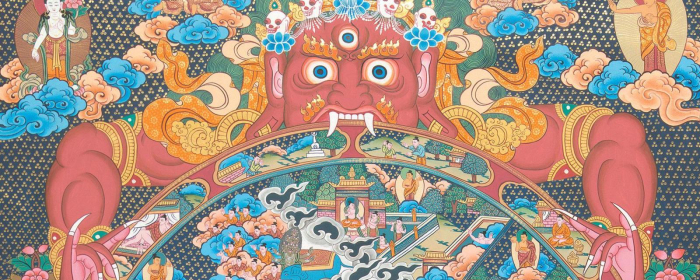

Do you ever feel like you’re trapped in a hamster wheel, while the lord of hell sinks his tusk-sized fangs into you? If so, you might feel a jolt of recognition upon seeing a Buddhist thangka painting by the Nepalese Master Buddha Lama. It’s been created for an exhibition of Buddhist artworks and manuscripts now at the British Library in London, featuring scrolls, artefacts and illuminated books spanning 2,000 years and 20 countries.

Although Buddhist principles like mindfulness have filtered into mainstream Western culture, other key tenets might not be as well-known. According to Buddhist cosmology, life is suffering experienced within the cycle of birth, death and rebirth. In Lama’s painting, we are in the big wheel that Yama, the lord of hell, is holding. (His facial hair is on fire and he wears a crown of skulls.) At the centre of the wheel are three animals symbolising the root causes of suffering, the ‘three poisons’: ignorance (pig), attachment (rooster), and anger (snake). The latter two come out of the mouth of the pig: ignorance is the primary obstacle to achieving anything, take note.

This thangka painting depicts the wheel of life (Credit: Master Buddha Lama, Sunapati Thangka Painting School, Bhaktapur, Nepal)

The ferris wheel of samsara (rebirth) rotates on this hub. The slice of pie at the top represents the realm of the gods (a gilded cage); the one on the bottom is hell. The others are the realms of demi-gods and humans (top half), and animals and ‘hungry ghosts’ (bottom half). People who are ruled by their cravings are reborn as hungry ghosts. Rebirth in the human realm is fortunate because it offers greater opportunities to escape samsara and achieve nirvana – the extinguishing of desire.

One dies and is reborn in the various sectors of the wheel according to one’s conduct. The more materialistic you are, the more ruled by passions, the more unpleasant your realm of existence. Ignorance is absolutely no excuse.

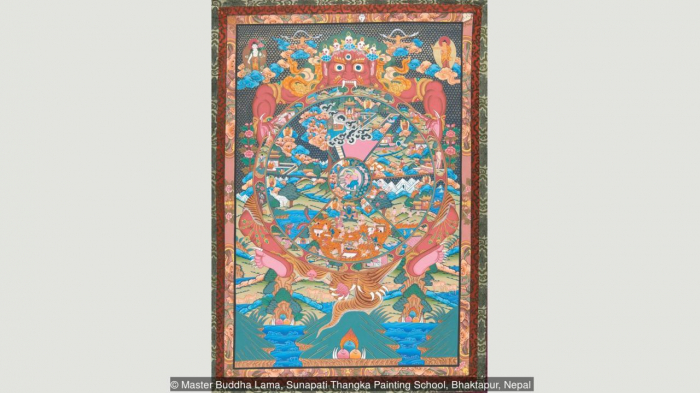

A gilded wooden statue, thought to have been commissioned by the last king of Burma, shows the Buddha in a healing pose (Credit: Trustees of the British Museum)

The British Library’s exhibition offers insights via objects that are as much artworks as artefacts. At the entrance, a 19th-Century gilded Buddha holds a myrobalan, a fruit that is a metaphorical cure for the three poisons. Among his other poses, the Buddha is often depicted as the great healer of human suffering. A Buddha is present in the upper corners of the thangka painting, to show us the way to the exit. The way off this mirthless amusement park ride is to follow the Buddha’s teachings, and the exhibition presents these in stunning profusion.

It also questions common misconceptions. “There is no consensus whether Buddhism is a religion or not,” Jana Igunma, the curator of the exhibition, tells BBC Culture. Buddhism has no “supreme divine being or creator god”; the Buddha is more like a teacher, a guide, and one studies his philosophy and his life by way of texts and illustrations. The media that have carried these over the millennia are fascinating.

As many as 500 million people worldwide might identify themselves as Buddhists, but there is no way of knowing for sure, because Buddhism isn’t exclusive: you can practise it, or adopt elements of it, any way you want. Nobody is going to tell you you’re doing it wrong. Also, Buddhism isn’t evangelical: whether or not you choose to listen to the Buddha’s teachings is on you. Perhaps you aren’t ready, and need to spend more time in the realm of the animals or of the hungry ghosts?

Buddhism is focussed on preserving and transmitting the teachings of the Buddha, and commentary thereon; and throughout history, it’s been quick to innovate and exploit transcription and printing technologies. It is one of the great drivers of human civilisations. Woodblock printing, for example, was crucial to the spread of Buddhism across East Asia, and in turn, Buddhism helped to spread printing techniques. As Igunma points out, “The Buddhist textual tradition has been an important part of world [civilisation]. The diversity of writing materials and the creativity in the production of manuscripts and books is fascinating… Buddhists were and continue to be keen adopters of new technologies.”

The way of the word

Depending on the region of the world and the historical period, Buddhist manuscripts and books have been created on a wide range of materials, including stone, palm leaves, precious metals, ivory, cloth, paper and silk. The Buddha’s teachings are written in Sanskrit, Pali, Chinese, Tibetan, Japanese, south-east Asian languages, and subsequently Western languages. As Igunma observes, in the exhibition there are “objects from 20 countries in even more languages and scripts”.

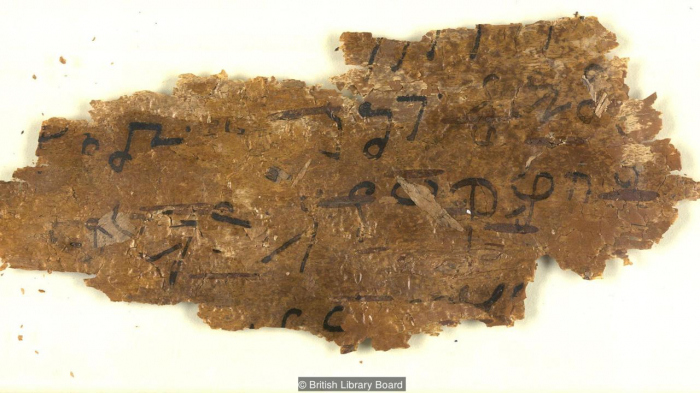

These gold sheets are from the Pyu kingdoms, and date to the 5th Century AD; they were excavated in Burma in 1897 (Credit: British Library Board)

All are distinguished by the thoughtfulness, delicacy, and beauty with which they celebrate the life and ideas of the Buddha; as well as by the ingenuity of the media of transmission. An early example of Buddhist text engraved in Pyu script on gold sheets demonstrates how exquisite and solid the Buddhist textual legacy can be.

Palm-leaf manuscripts were a prevalent form of textual transmission from the time of the Buddha until the development of the printing press

Palm-leaf manuscripts were a prevalent form of textual transmission from the time of the Buddha until the development of the printing press; from 500 BC up to the 19th Century. Palm leaves are readily available throughout India and south-east Asia. When trimmed, treated, and dried they take ink well, and they are durable in the humidity of south and south-east Asia. They result in ‘books’ composed of very large, oblong folios – a good paper equivalent many centuries before paper came into use in Europe.

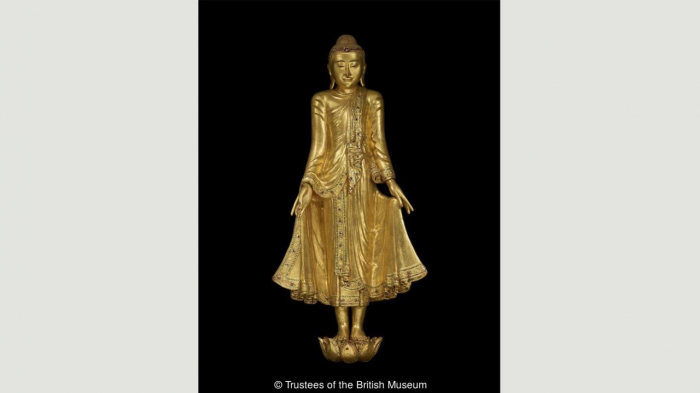

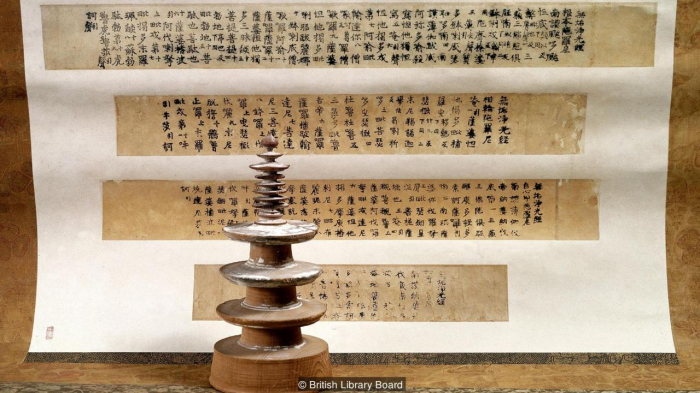

The exhibition includes complete texts and fragments; this is from a 1st-Century scroll (Credit: British Library Board)

To begin near the beginning, the exhibition includes fragments of Gandharan scrolls from the 1st Century AD, created about 400 years after the historical Buddha is thought to have lived. These are of outstanding importance: as Igunma observes, they are “the oldest extant written scriptures of Buddhism”. The scrolls were made of birch bark in Gandhara, an ancient Buddhist kingdom in the region of present-day Afghanistan and Pakistan. They contain Buddhist scriptures in the Gandhari language and Kharosthi script. The fragments seem so ancient and fragile, yet the script on them remains hauntingly clear.

This 10th-Century scroll illustrates the Sutra of the Ten Kings, describing ten stages during the transitory phase following death (Credit: British Library Board)

We make a jump in refinement of manuscript transmission, to a version of paper as we know it, with the Sutra of the Ten Kings, which was found in a cave near Dunhuang, north-west China, amidst a huge cache of documents. By this time, paper had been in use in central and east Asia, where the dryer climate lent itself to finer material, for centuries. The 2.5m-long painted paper scroll Sutra dates to the 10th Century, and depicts the Ten Kings of the Underworld, sitting behind desks, in judgement on people’s good and evil deeds. A secretary stands beside the king taking notes. The judged souls wear wooden cangues, and are driven by a gaoler. The six possibilities of rebirth are depicted, from hell to Buddhahood.

The Lotus Sutra is seen by many as a summary of the Buddha’s teachings; this 17th-Century scroll from Japan is written in Chinese characters (Credit: British Library Board)

Japan is an important centre for Buddhism, and for refined manuscript creation. Of the exhibits from Japan, two are extraordinary. A copy of the Lotus Sutra was commissioned by Emperor Go-Mizunoo in 1636. The Lotus Sutra is a key text in the Mahayana tradition of East Asia, and is seen by many of its adherents as the summation of the Buddha’s teachings. On display is the scroll of chapter eight of 28 chapters. The lavishly illustrated scroll contains gold and silver ink on indigo-dyed paper. The segment reproduced in the photo here shows the Buddha promising Buddhahood to his 500 disciples.

The ‘Million Pagoda Charms’ are among the earliest examples of printing in the world (Credit: British Library Board)

Igunma also draws our attention to the ‘Million Pagoda Charms’, containing incantations to invoke the protective deities, because “they are the earliest examples of printing in Japan, and among the earliest in the world”, dating back to between 764 and 770 AD. Empress Shotoku ordered the charms, including Buddhist texts, to be printed on small strips of paper, and placed in miniature wooden pagodas; the pagodas were then distributed among the 10 leading Buddhist temples in western Japan. There is debate on the subject, but woodblock printing seems to have been used to create the documents. (The ‘Million Pagoda Charms’ were thought to be the world’s oldest printed documents until 1966, when a similar document was discovered that was believed to have been created before 751.)

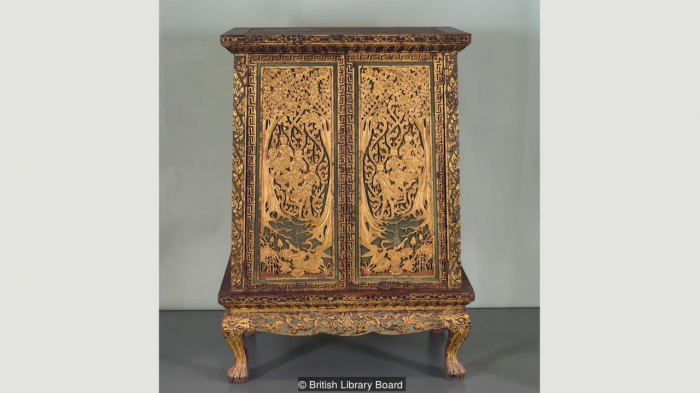

Chests like this were used to store manuscripts in temple libraries (Credit: British Library Board)

The library – storage of documents – is of course important to Buddhism and its many texts. This too is executed with great flair. Jana Igunma personally regards one of the highlights of the exhibition as “a small arrangement of manuscript chests and a book cabinet which give visitors an impression of what a temple library in mainland south-east Asia looks like”. A photo here depicts a 19th-Century Thai carved and gilded wooden manuscript chest for the storage of Buddhist texts. It is raised on legs, and closes and locks to protect manuscripts from moisture and pest damage. Igunma notes that temple libraries are very sacred places, where “one can find true solitude and tranquillity”.

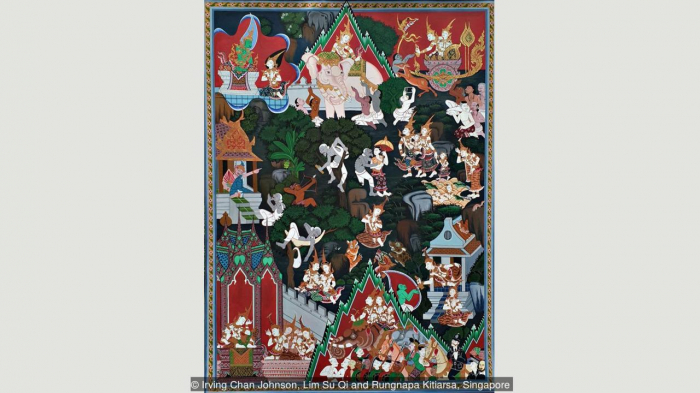

The Vessantara Jātaka tells the story of one of the Buddha’s past lives (Credit: Irving Chan Johnson, Lim Su Qi and Rungnapa Kitiarsa, Singapore)

Finally, to end in the present, the British Library commissioned a painted wall hanging – a new Buddhist ‘text’ – of the Vessantara Jātaka by three Singaporean artists, Irving Chan Johnson, Lim Su Qi, and Rungnapa Kitiarsa. It is painted in the style of a 19th-Century Thai banner painting, a visual teaching aid. It is an outstanding work of art, and depicts 13 scenes from the Buddha’s previous life in order to teach about the Buddhist values of generosity and charity.

On the way out of the exhibition there is a large standing bell of the sort used in temples for meditation and chanting. Visitors are invited to strike it with a mallet. If Buddhism has a characteristic ‘sound’, this must be it. The tone, so characteristic of Buddhism, is deep, clear, and thrilling. It is the sound of awakening, a call to attention.

Another distinctive sound comes through the ancient language Pali, regarded as close to the language the Buddha spoke. The Pali canon of the Buddha’s teachings is an important fount of later translations – and recitations of those texts can be listened to online. Like the bell, it’s an immediate entrypoint into something that has been preserved, via scroll and manuscript, for millennia.

BBC

More about: language