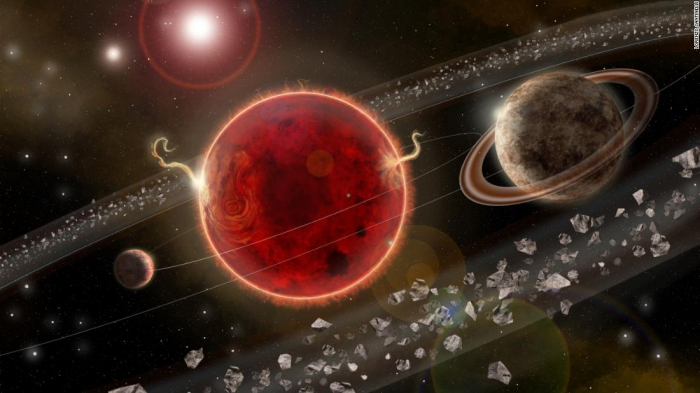

Proxima Centauri is the closest star to our sun. It's a low-mass red dwarf star known as an M-class dwarf. The star is in a triple star system known as Alpha Centauri, including binary pair Alpha Centauri AB.

All of these stars are within the faint Centaurus constellation, which can't be seen with the unaided eye.

After the discovery of the first planet around Proxima Centauri, researchers speculated about the existence of another planet in the system. Astronomers used the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array of telescopes in Chile to trace light signals that appeared to be coming from that direction.

The authors of a new study, published Wednesday in the journal Science Advances, were able to look at more than 17 years of radial velocity data from the well-studied star system and determine if the signal belonged to an orbiting planet.

The radial velocity method is based on gravity and the Doppler effect, in which light increases or decreases in frequency as a source and observed objects move toward or away from each other.

Stars don't remain completely still when they are orbited by planets; they move in small circles as a response to the pull of gravity from the planets. These movements change the light wavelength of the star, going between red and blue depending on the location of the planet. Tracing the shifts can help astronomers find planets.

The researchers can't rule out that the signal could be due to activity of the star's magnetic field, but the signal they traced occurred over a period of 1,900 days -- a strong indicator that a planet is present.

"Even the closest planetary system to us may retain interesting surprises," said Fabio Del Sordo in an email, study author and postdoctoral researcher in the department of physics at the University of Crete. "Proxima Centauri hosts a planetary system that is much more complex than we knew, and we do not know how many unknown features are waiting to be discovered."

Even though Proxima b is within the habitable zone of its star, meaning liquid water could exist on the surface, that doesn't mean it's actually habitable. And the radiation it likely faces has likely stripped away key elements for life like hydrogen, oxygen and nitrogen.

The newly discovered planet is intriguing because further study could reveal how low-mass planets form around low-mass stars, the researchers said. And this particular planet flips the typical theory of super-Earth planet formation on its head.

It's beyond the "snowline" of the system, which suggests any water on the planet would be frozen. Super-Earths typically form near the snowline, but not beyond it.

"The formation of a super-Earth well beyond the snowline challenges formation models, according to which the snowline is a sweet spot for the accretion of super-Earths, due to the accumulation of icy solids at that location," said Mario Damasso, study author and postdoctoral researcher at Italy's National Institute for Astrophysics. "Or it suggests that the protoplanetary disk was much warmer than usually thought. In general, there's nothing preventing the existence of Proxima c there where we spot it, but the formation and evolutionary history is a subject worthy of deeper investigation."

The European Space Agency's Gaia mission, which is creating a 3D mission of our galaxy, could help refine the signal of the second planet and provide more answers in the future.

"Proxima Centauri is the nearest star to the sun, and this detection would make it the closest multiplanetary system to us," Del Sordo said.

CNN