The COVID-19 pandemic has offered two key lessons for developing countries: They must build on their own endowments and tackle infrastructure bottlenecks in sustainable ways. What will it take to ensure that foreign investment – in particular, Chinese investment in Africa – supports these objectives?

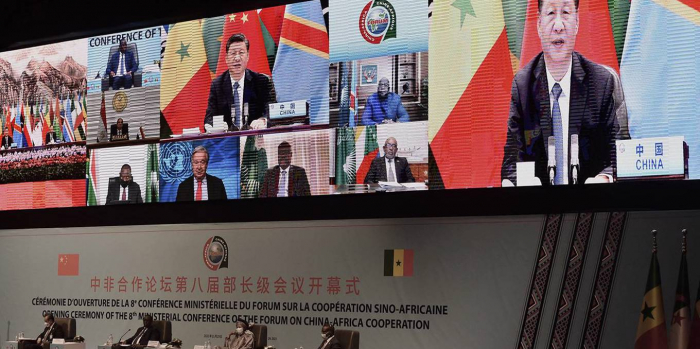

The eighth triennial Forum of China-Africa Cooperation was recently held in Dakar, Senegal. At past forums, China has announced large development-financing packages. But this year, Chinese President Xi Jinping opened the FOCAC by pledging another billion doses of COVID-19 vaccines and more private-sector equity investment to Africa. This is just one sign of how profoundly the development landscape has changed in the pandemic’s wake.

The COVID-19 crisis has forced policymakers and development professionals worldwide to regroup and rethink their approaches. The continued emergence of new variants, together with the increasingly obvious consequences of climate change, has reminded us of how little control over nature humans really have. And travel restrictions and trade disruptions have highlighted the risks that lie in global interdependence.

This brings us to the first critical lesson of the pandemic: Development starts at home. Rather than depending on cross-border flows, countries must recognize and build their own wealth – that is, the assets and endowments that lie within their borders.

In the past, wealth has not gotten nearly enough attention from economists and policymakers. For starters, as voices from the Global South have increasingly lamented, evaluations of debt sustainability – such as the joint International Monetary Fund-World Bank Debt Sustainability Analysis Framework – have tended to focus narrowly on liabilities, without taking adequate account of the asset side of the public-sector balance sheet. On the positive side of the ledger, flows, such as GDP, have attracted far more attention than the stocks of assets and net worth.

This reflects the predominance of short-term thinking. Whereas GDP indicates how much monetary income or output a country produces in a year, wealth also covers the value of the underlying national assets, including the human, natural, and produced capital that form the foundations of a country’s comparative advantages. As such, wealth accounting provides essential insights into a country’s prospects for maintaining and increasing its income over the long term.

Yet there is currently a shortage of information on the value of public-sector assets and net worth. The World Bank’s Changing Wealth of Nations 2021 report goes some way toward filling this knowledge gap, making it an invaluable resource for policymakers today.

Supply-chain disruptions have clearly inflicted severe pain on the world. But a second lesson of the pandemic is that many low- and lower-middle-income countries continue to suffer more fundamental deficiencies, such as a lack of health-care personnel and resources, from hospital beds to ventilators. For some, it is the inability to deliver clean water, electricity, and sanitation that is choking the economy.

After 70 years of development aid and cooperation, how is it possible that many countries remain stuck in low- or lower-middle-income traps without sufficient capacity to meet their citizens’ basic needs? Both market and government failures – rooted not least in the longstanding neoliberal orthodoxy – can be blamed.

A core problem is that all that aid did not adequately address infrastructure bottlenecks. This partly explains why African countries have often welcomed Chinese investment.

As Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi noted in his 2020 FOCAC speech, China financed, constructed, and completed thousands of hard and soft infrastructure projects in Africa in the first two decades of this century. This includes over 6,000 kilometers (3,728 miles) of railways in Africa, and roads covering roughly the same distance. China has also constructed nearly 20 ports, over 80 large-scale power plants, more than 130 medical facilities, 45 stadiums, and 170 schools.

This has gone a long way toward supporting Africa’s structural transformation. According to our study, some 75-78% of China-financed projects completed in 54 African countries between 2000 and 2014 addressed one of five key bottlenecks. In other words, seven out of ten completed projects met the basic needs of the continent’s people. Moreover, in as many as 18 African countries, the manufacturing sector has been trending upward since 2011.

But there is still much room for improvement. Targeting problems afflicted 22% of completed hard-infrastructure projects and 26% of soft-infrastructure projects, meaning that they were not genuinely demand-driven. This can lead to “white elephants.” Moreover, research by the Boston University Global Development Policy Center has revealed concerns about the social and environmental effects of these projects. Country-specific studies are needed.

The good news is that China has committed to stop financing coal-fired power plants and to invest more in renewables. According to updated Chinese aid data, over 60% of Chinese investment projects are in green sectors. The bad news is that China’s two large policy banks have reduced their overseas lending sharply since 2017, and there is still ample room to improve targeting.

FOCAC is a good place to start addressing these issues – and, more broadly, to revamp cooperation between China and Africa to reflect the lessons of the pandemic. This means, first and foremost, committing to ensure that aid or development cooperation is demand-driven, addressing each country’s specific needs.

A market-based approach – which combines trade, aid, and investment – could be integral to success, as it would help to ensure that incentives are aligned among equal partners. Crucially, all China-financed projects must meet environmental, social, and governance standards. Soft-infrastructure projects that bolster health care, education, and governance should be top priorities.

More broadly, China must boost standardization and transparency in its foreign-aid and cooperation projects. Ultimately, this requires the enactment of a comprehensive foreign-aid law, focused on ensuring transparency and accountability.

It is also critical to engage more actors, including the private sector and multilateral development banks, with a view toward blended financing. Given the long-term nature of the needed investments, all participants need to embrace the concept of “patient capital.”

The post-pandemic agenda is clear: countries must build on their endowments and tackle infrastructure bottlenecks. With the right approach to policy and financing, countries can mobilize the resources needed to clear a path toward sustainable development.

Justin Yifu Lin, a former chief economist at the World Bank, is Dean of the Institute of New Structural Economics and Dean of the Institute of South-South Cooperation and Development.

Yan Wang, a former senior economist at the World Bank, is a senior researcher at the Boston University Global Development Policy Center.

More about: