Little progress in Thai south talks

The Bangkok Post reported Thursday that the insurgents, represented by a new umbrella organization called Majlis Syura Patani, or Mara Patani, asked that members already sentenced for violent acts receive an amnesty and that immunity from criminal prosecution be extended to those being sought who are yet to be detained.

The insurgents also asked for the peace talks to be put officially on the national agenda through a parliamentary vote.

While not rejecting the two requests outright, Thai officials -- led by Gen, Aksara Kerdpol -- said Thai authorities must take time to consider the requests.

“There are a lot of details still to be discussed, but in principle we can agree on the proposals,” General Nakrob Boonbuathong, a member of the Thai delegation, told Malaysian Website BenarNews.

With regard to bringing the dialogue to the national agenda, Boonbuathong would only say: “As we talk to Mara Patani, it means we accept them.”

On its side, the government delegation focused on the establishment of guaranteed “violence-free zones” in the south.

“We want the insurgents to single out the areas, as they know which areas they can control 100 percent,” General Aksara Kerdpol told the Bangkok Post.

Mara Patani is made up mostly of old insurgent movements -- Barisan Revolusi Nasional (BRN), three factions of the Pattani Liberation Organization, the Gerakan Mujahideen Islam Pattani and the Barisan Islam Pembebasan Patani -- who were part of previous talks, but as separate entities.

Malaysian host and facilitator Zamzamin Hashim -- the former chief of Malaysia`s intelligence agency -- and his secretariat were involved in organizing and launching the group.

Experts, however, have maintained that it is unclear just what degree of control Mara Patani has over the other outfits.

This week`s talks, which took place in a police safe house in the Malaysian capital, were the third between Thai officials and the rebel groups since the Thai military seized power in a May 2014 coup.

The two previous sessions were in June.

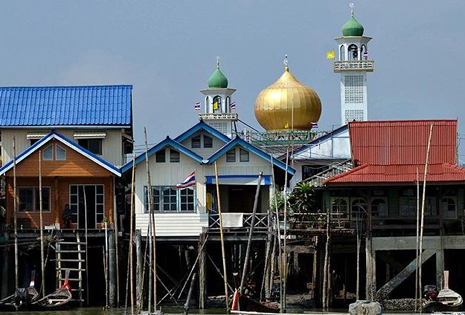

The southern insurgency is rooted in a century-old ethno-cultural conflict between Malay Muslims living in the provinces of Pattani, Yala, Narathiwat and some districts of Songhkla and the Thai central state where Buddhism is considered the de facto national religion.

Armed insurgent groups were formed in the 1960s after the then-military dictatorship tried to interfere in Islamic schools, but went quiet from the end of the 1980s.

In 2004, a rejuvenated armed movement -- composed of numerous local cells of fighters loosely grouped around the Barisan Revolusi Nasional (BRN) or National Revolutionary Front -- re-emerged. Since then, the conflict has killed 6,400 people and injured over 11,000, making it one of the deadliest low-intensity conflicts on the planet.

A peace dialogue was engaged by the elected government of Yingluck Shinawatra in 2013, but was suspended in December of that year because of the political tensions in Bangkok.

The May 22, 2014 coup, which overthrew Shinawatra’s government and brought a junta to power, added more uncertainty to a possible peaceful solution to the conflict, even if the military are continuing the dialogue, albeit under a closed meeting format.

In a recent report, the International Crisis Group, a Brussels-based think tank, recommended -- among others -- suggestions that the Thai government “recognize an official dialogue process with Malay militant groups as a national-agenda priority, endorsed by the National assembly”.

It also suggested militant groups “recognize that self-determination is compatible with preservation of Thailand’s national integrity”.