Although the school closed in 1872, the home for men still exists. Today, 40 men – called “brothers” – quietly inhabit the Charterhouse. In order to be eligible, they must be at least 60 years of age, professional, unmarried, in good health, in financial need and in need of companionship. The neediest come first; while the organisation is Christian, attendance at chapel is not compulsory. When applying to join the community, the men are asked: “How would you cope with community life?”

Recently, I spent a day at the Charterhouse. The atmosphere was half monastic and half donnish, and the overwhelming sense I got from the ever-bantering brothers was a sense of gratitude that they had found such a congenial place to retire. As former teacher Duncan Ellison, 71, put it: “I dreamed of this kind of life and the extraordinary thing is that it happened.”

Former Church of England deacon and priest Brooke Kingsmill-Lunn, 83, said, “The structure here gives a rhythm to the day… One of the most common problems I saw as a parish priest was loneliness. That is not an issue here.”

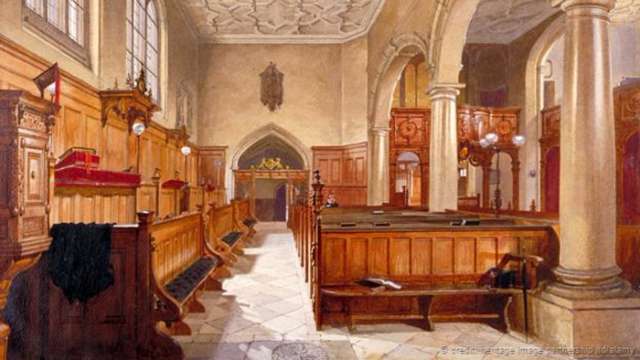

The day started at 8 am with voluntary morning prayers in the chapel, home to the ornate tomb of Sutton. Breakfast was served at 8:30 am, with a choice of a full English or toast and muesli.

After that was free time. The brothers might clean their flat, go for a walk, see the doctor or while the morning away in the gardens.

Formal lunch was served in the Great Hall at 1 pm: a jacket was required; most brothers wore a tie. We stood by our chairs at the long tables while a bell was rung, grace read and Sutton thanked. Pasta was followed by apple crumble. Some brothers paired their meal with half a pint of ale. The atmosphere was cheerful and chatty.

When I asked if any of them did paid work, I was told that one recent brother had. “There is nothing to stop you working. It’s not against the rules,” one of the men said. Instead, I learned, there is really just one rule: “You must get on with people.”

So, I asked, is the motto here “live and let live”?

“More ‘live and let die’,” quipped the well-fed and sardonic brother to my left, a retired priest called John Cooper.

Their attitude to death was pretty cheerful. I was told that the top row of mail pigeonholes, allocated to the longest-serving brothers, was called “death row”. I heard Charterhouse called “the waiting room”, while the infirmary was known as “the departure lounge”. As brother Dudley Green put it, “When a brother dies, we miss them. But it is a comfort to know that they have been well taken care of.”

After lunch there was more free time. One group near the infirmary were having a singing lesson. Two brothers came in from a lunchtime pint at the pub. Others ambled off to write letters or to have a nap.

In the company of brother Phil Stewart, I strolled through the beautiful gardens, passing through an idyllic scene of pink foxgloves, monkshood, lilies, pink and yellow roses, lavender and purple alliums. The hum of London traffic could be heard, but seemed very far away.

“I have found happiness here. It is heaven on Earth,” said Stewart, 68, an American who spent his adult life in Chicago working as a hotel piano player.

Evening prayer was at 5:30 pm, followed by dinner, an informal buffet, at 6:30 pm. Afterwards the brothers went out to concerts, the pub, watched television in their rooms, played bridge or attended a poetry reading group.

In the next few years, the Charterhouse may get busier: a museum outlining its remarkable story is planned to open in the autumn of next 2016 and there are plans to create accommodation for 10 more brothers. Yet it’s likely that this will remain the quietest corner of London – and a haven of conviviality and civilisation. If my wife leaves me and my businesses collapse, I know what to do.

More about: