Repeating cosmic radio blast adds mystery to their origins

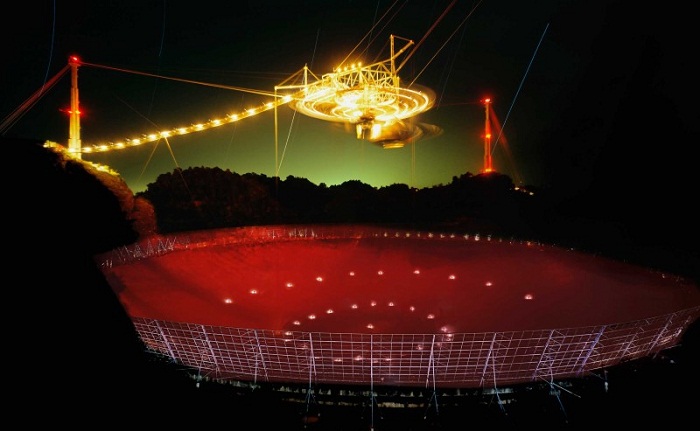

The original burst, known as FRB 121102, was picked up by the Arecibo radio telescope in Puerto Rico. Initial follow-up observations didn’t spot anything, but in May and June 2015 the team discovered 10 additional bursts, much to their surprise. “It’s fair to say we were expecting to see none,” says Hessels.

Finding FRBs that repeat provides a clue to their origins. “It tells us that this wasn’t some kind of cataclysmic explosion that destroyed the source,” says Hessels, such as the merger of two neutron stars.

Instead, he thinks the signal must come from a rotating source that repeatedly throws radio waves in our direction, similar to the pulsars seen in our galaxy. “If it is outside our galaxy, which it appears to be, it must be something like a pulsar on steroids,” he says.

Cosmic conflict

The result contradicts a paper published last week by Evan Keane at the Jodrell Bank Observatory in the UK and his colleagues. They reported a connection between an FRB and a distant galaxy with a radio “afterglow”, which they believe was likely to be caused by the kind of catastrophic merger Hessels’s observation rules out.

“Either one of the two things is incorrect, or there are two different types,” says Hessels. That’s not without precedent – similar signals known as gamma ray bursts puzzled astronomers until they realised the bursts came in both short and long varieties.

This week Peter Williams of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and his colleagues also reported they had seen a second afterglow from Keane’s galaxy, which shouldn’t happen if a merger is the cause. It could just be a coincidence, in which case we don’t know if the cataclysmic cause is possible. “I don’t think last week’s paper provides any evidence one way or another,” says Williams about Keane’s paper, but Hessels’s paper makes it clear that there must be a source of repeating FRBs. “Detecting this repeating signal is fundamentally a more robust result.”

Ultimately, astronomers need to make more measurements of these fleeting signals to figure out the puzzle. Arecibo is the most sensitive radio telescope in the world, which could be why it is the only one to have picked up repeated FRBs.

Pointing it in the direction of other FRBs should clear things up, says Hessels. “If, for a few more of those sources, we can find additional bursts, then it will look quite plausible that they all repeat,” he says. “It’s just a matter of sensitivity and how long you wait.”