The human immune system is one of the most effective defence mechanisms known to nature. It can ward off myriad microbial invaders: bacteria, viruses and parasites. It is sometimes overwhelmed by disease, of course, but the billions of men and women who now live on Earth are a testament – at least in part – to the effectiveness of their immune defences.

However, on occasions they go too far. Instead of killing off invading organisms, our immune systems turn on our own tissue and attack it. Conditions such as type 1 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, and lupus are all triggered in this way, very often with deeply unpleasant consequences.

In the case of rheumatoid arthritis, immune cells – mainly lymphocytes and macrophages – start to attack the tissue that makes up joints, and these become painful, stiff and swollen. Around one-third of those who develop rheumatoid arthritis will have stopped working within two years of its onset, so painful are its effects. And given that the disease affects more than 400,000 people in the UK, its financial impact is also high: estimates suggest it costs the economy between £3.8bn and £4.8bn a year.

Similar conditions include ankylosing spondylitis, which affects the joints in the spine, again causing pain, stiffness and restricted movement. Around 200,000 people in the UK are affected, at an estimated annual cost of up to £3.8bn to the economy. Meanwhile, juvenile idiopathic arthritis affects 12,000 children under 16, many of whom will suffer severe limitations in movement in their adult life.

Trying to understand exactly why a person’s immune system turns on the body has proved to be tricky, a hindrance to developing cures. “In most cases of rheumatoid arthritis, for example, we can provide treatments that alleviate the worst symptoms, but patients will have to take these drugs for the rest of their lives,” says immunologist Prof Adrian Hayday, of the Francis Crick Institute in London.

Recently, however, researchers, including Hayday, have found an unexpected ally in their battle against autoimmune disease: cancer. It is an unexpected link, but a promising one, as Hayday explains. “In the past five years, there has been a revolution in the way we treat some cancers – by using immunological techniques,” he told the Observer. “These have had unprecedented positive results against metastatic melanomas and non-small-cell lung carcinoma. By giving patients drugs, we have been able to turn up their immune systems so they successfully mount attacks against these cancers. We have armed their immune systems and made them active.”

It is one of the most important developments in the battle against cancer this century. But side-effects have recently emerged. “There are around 140 patients undergoing immunotherapy for their cancer at Guy’s hospital in London, where I do my clinical research,” says Hayday. “Our cancer drugs boost our patients’ immune systems to help them kill off their tumours. But of course, that is the same sort of thing that happens in people with rheumatoid arthritis and diabetes: something triggers their immune systems so that they become overactive and souped-up.

“As a result, some of the cancer patients – happily, not too many – who are being treated with immunotherapies are beginning to develop rheumatoid arthritis and type I diabetes. By boosting their immune systems,” Hayday said, “we have exacerbated any tendency for these people to have had these conditions and we are beginning to see the occasional case arising among our cancer patients.”

The appearance of these conditions raises important issues for cancer patients. “We have to be very careful about ensuring quality of life for people once they have undergone cancer treatments, so obviously this is a concern,” Hayday says.

However, there is also a more positive consequence of the discovery that cancer immunotherapies have the effect of triggering autoimmune diseases in some cases: “For the first time, we now have a chance to study rheumatoid arthritis at its earliest stages, and that is tremendously important.”

At present, people are not diagnosed with the condition until symptoms have already made their lives so unpleasant they have gone to see their doctors. “By then the condition is well established, and that makes treating it difficult,” said Hayday. “But if we have people in the ward who never had the disease but who, after we have given them drugs for their cancer, begin to develop rheumatoid arthritis or type 1 diabetes, then we can study and understand autoimmune diseases like these for the very first time.”

As a result, research – backed by Cancer Research UK and Arthritis Research UK – has been launched with the aim of uncovering the roots of autoimmune disease from research on cancer patients. “You know that when you give a patient an immunotherapy drug for their cancer, if they are going to get an autoimmune disease, they are probably going to get it over the next few months,” says Prof John Isaacs, of the Institute of Cellular Medicine, Newcastle. “So, we can monitor them – take regular blood samples and follow these patients very carefully – if they are happy for that to happen. In this way, we can get a handle on the very first events that lead to them getting autoimmune cells. Can we see if something is happening to their B-cells or their T-cells that later leads them to get rheumatoid arthritis or another autoimmune condition, for example?”

The scientists involved stress that their work is only now beginning and warn that it will still take several years’ research. Nevertheless, uncovering the first stages of an autoimmune disease emerging in a person’s body should give researchers a crucial lead in ultimately developing treatments that will prevent or halt a range of conditions that currently cause a great deal of misery and require constant medication.

“Autoimmune diseases are horrible afflictions,” adds Isaacs. “Now, for the first time, we can think seriously of halting them in their tracks one day.”

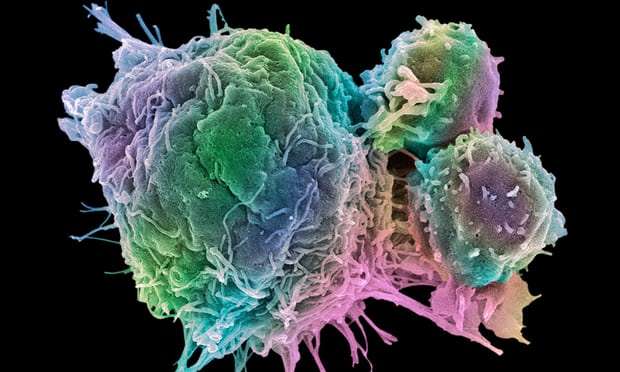

Our immune defences consist of a range of cells and proteins that detect invading micro-organisms and attack them. The first line of defence, however, consists of simple physical barriers like skin, which blocks invaders from entering your body. Once this defence is breached, they are attacked by a number of agents. The key cells involved here are white blood cells (leukocytes), which seek out and destroy disease-causing organisms. There are many types. Neutrophils rush to the site of an infection and attack invading bacteria. Helper T-cells give instructions to other cells while killer T-cells punch holes in infected cells so that their contents ooze out. After these macrophages clean up the mess left behind.

Another important agent is the B-cell, which produces antibodies that lock on to sites on the surface of bacteria or viruses and immobilise them until macrophages consume them. These cells can live a long time and can respond quickly following a second exposure to the same infections. Finally, suppressor T-cells act when an infection has been dealt with and the immune system needs to be calmed down – otherwise the killer cells may keep on attacking, as they do in autoimmune diseases. By slowing down the immune system, regulatory T-cells prevent damage to “good” cells.